Voting

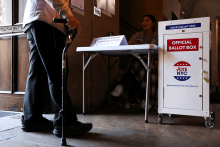

During the 2024 August primary election, a Detroit man called the Election Protection Hotline to report an accessibility issue at a polling location. The man, who had a mobility disability, went to vote at a church in the city where he was met with a flight of stairs but no ramp. He was forced to get out of his wheelchair and climb the stairs on his hands and knees before he could cast his vote.

As we officially enter the season of primaries, advertising campaigns, and debates, faith communities are as central to the election process as they ever have been. Even with the nationwide decline in religiosity and trust in institutions, religious leaders and congregations are central community builders for millions of people in the U.S.

WHEN I WAS 8 years old, I fried an egg on the street. Well, I tried to fry an egg on the street. It had been a particularly brutal summer in Florida. On the days when the playground slides were too hot to go down, my mom would say, “It’s hot enough to fry an egg on the sidewalk!” I kept my eyes glued to that splattered yolk for two hours until a car tire brought the grand breakfast experiment to an end. Frying eggs on sidewalks was how I learned to conceptualize extreme heat.

When it comes to describing climate change urgency in Black communities, Heather McTeer Toney taps into something simple: streetlights. In Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America’s Urgent Call for Climate Solutions, she writes that when she was growing up, kids could play all day outdoors, but they had to be home “before the streetlights came on.” As twilight settled in and streetlights started to flicker, kids would call out, “Hurry up, we ain’t got all day!”

“Right now, that same call to action is carried in the waves of massive hurricanes, on the winds of devastating firestorms, and in the uncharacteristic heat of winter,” McTeer Toney writes. Using a familiar metaphor, she issues a call to action of her own.

Climate change and environmental justice is not foreign to McTeer Toney or the communities she writes about. At age 27, she was the first female and youngest person to serve as mayor of Greenville, Miss., where she was born and raised. As mayor, she brought the city out of debt and established sustainable infrastructure repair. For three years, she led the Environmental Protection Agency for the southeastern United States. While at the global nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund, she addressed environmental policy and community organizing within and beyond the U.S. This spring, McTeer Toney became executive director of Beyond Petrochemicals, a campaign to stop the rapid expansion of petrochemical and plastic pollution, particularly in the Ohio River valley and along the Gulf Coast.

McTeer Toney and her family attend Oxford University United Methodist Church in Oxford, Miss. I spoke with her by phone about her work, her book, and the hope her faith demands. — Christina Colón

In the immediate aftermath of Jan. 6, 2021, I naively believed that the violent attempt to overturn the 2020 election outcome would serve as a breaking point for the nation and the Republican Party. Despite the party’s anti-democratic slide, including so many embracing the lie that the 2020 election was stolen, I thought the collective horror of the day — felt across the political spectrum — would awaken everyone to the danger that former President Donald Trump and his enablers posed to our democracy. Of course, we now know that isn't what happened.

I know I’m not alone in feeling exhausted. In 2018, More In Common — a nonprofit that researches what’s driving political polarization — found that two-thirds of Americans share a series of characteristics that make them a part of what they call the “exhausted majority.” This group of people is “fed up with the polarization plaguing American government and society,” feels forgotten in the public discourse, and often has flexible views that don’t fit consistently in the Left/Right binary. Yet, they believe we can still find common ground. Sound familiar?

We can honor King’s vision by working to restore the voting rights that he knew were so central to dismantling racism in this country. As King proclaimed, “Voting is the foundation stone for political action.”

I remember the flood of emotions I felt almost a year ago when I heard that the major news networks were calling the 2020 election results: overwhelming relief and renewed hope. Far beyond a victory for then-to-become President Joe Biden, it felt like a victory for our democracy — and an imperative to resuscitate, revitalize, and reinvent that democracy.

Fast forward a year: I’m filled with a festering weariness and escalating heartache.

As many people in the United States prepared for the holiday weekend, the Supreme Court’s conservative 6-3 majority upheld two laws that restrict voting in Arizona. The first law the court upheld disenfranchises voters if they cast a ballot in the wrong precinct, invalidating not just their votes for local races, but also their entire ballot, including votes cast in U.S. presidential elections or Senate races, even though all eligible voters in Arizona can vote in those races regardless of the district where they live. The other law prohibits most people from delivering another voter’s absentee ballot to a polling place, making it a crime for anyone but a family member or caregiver to do so.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday endorsed two Republican-backed ballot restrictions in Arizona that a lower court found had disproportionately burdened Black, Latino and Native American voters, handing a defeat to voting rights advocates and Democrats who had challenged the measures.

The 6-3 ruling, with the court's conservative justices in the majority, held that the restrictions on early ballot collection by third parties and where absentee ballots may be cast did not violate the Voting Rights Act, a landmark 1965 federal law that prohibits racial discrimination in voting.

In a statement, Bishop Reginald Jackson, who oversees Georgia's African Methodist Episcopal churches, said Home Depot had rejected requests to discuss the new law.

In president-elect Joe Biden’s acceptance speech on Saturday he “pledge[d] to be a president who seeks not to divide, but to unify. Who doesn’t see red and blue states, but a United States.”

Yet over the weekend, some social media users used their platforms to warn pastors not to conflate peace-building and unity with forced reconciliation.

Through Thursday, 9,009,850 have voted so far this year, with one day of early voting left. That amounts to 53 percent of registered voters. In 2016, 8,969,226 Texans cast a ballot in the presidential race.

The Supreme Court on Wednesday rejected a request by President Donald Trump's campaign to block North Carolina's extension of the deadline for receiving mail-in ballots in the latest voting case ahead of Tuesday's election.

Faith communities across the U.S. are looking to help further democracy by ensuring that 100 percent of the eligible voters in their congregations turn out for the 2020 election.

The work of unlearning racism and undoing our habit of exploitation — of the earth, of other bodies, and other neighborhoods — is long.

The Council on American-Islamic Relations of Minnesota has accused a private security company of violating the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by hiring ex-U.S. military Special Operations soldiers to patrol polling places. The company, Atlas Aegis, posted a job listing in early October looking for former Special Operations personnel to “[staff] security positions in Minnesota during the November Election and beyond to protect election polls.”

With four weeks to go before Election Day, more than 4 million Americans already have voted, more than 50 times the 75,000 at this time in 2016, according to the United States Elections Project, which compiles early voting data.

PEOPLE OFFER MANY reasons for not voting, from “one vote doesn’t matter” and “there’s no real difference between the parties” to the conviction that an election “won’t bring about real justice (or the reign of God).”

The latter, at least, is certainly true. Voting—even electing the best-available candidates for the most important positions in government—definitely won’t bring about the peaceable kingdom.

But who is ultimately elected—especially at the presidential level—can make a world of difference in the lives of those in the most vulnerable conditions. For instance, in the past three-plus years, more than 200 judges have been appointed to the bench, many of them to lifetime terms. Of that number, zero have been Black. And judicial appointment is only one of many powers in executive hands, which affect everything from education, housing, and immigration policies to whether our society makes the hard choices of confronting racialized policing and combating climate change.

Pamela Ebstyne King believes that “[t]hrough spirituality, people potentially have access to prosocial ideals and beliefs, a community to support them, and a source of transcendence that motivates behaviors aligned with their spiritual ideals.”

For many today, the Black freedom struggle has become a myth. Our ancestors are memorialized in their death while crucified in their life. For many, it has become a symbol of progress: a symbol of the progress of America, particularly white America, to finally “get it.” It is a powerful myth.