Racism

At a recent annual meeting, seminary presidents in the Southern Baptist Convention doubled down on the SBC’s dismissal of “critical race theory,” which examines the issues of embedded racism across institutions and culture in American society. CRT shows how white supremacy — the belief that some people are more valuable than other people because of their skin color — is not just a personal prejudice but a structural and societal practice in America.

The Electoral College has racist origins. Southern states were granted votes for three-fifths of their slave populations, even though those enslaved people were themselves unable to vote. This effectively gave white southerners an outsized influence on the electoral process until the end of the Jim Crow era. Today, the system favors voters in a small group of battleground states at the expense of most Americans and over-represents white voters while ignoring many voters of color. A growing chorus of legal and policy experts, along with the majority of Americans, believe it should change. However, the Electoral College’s racist legacy has also impacted efforts to change it.

Racism is on the ballot next week. Democracy is on the ballot next week. These two things two are inextricably linked because racism has disfigured American democracy from the founding of our nation. The road to a more perfect union has been long and uneven. And this road requires that we continually become a more perfect democracy and more just nation. And while our democracy will never be perfect, we must continually defend the rights, institutions, and laws that help safeguard our freedoms and advance the common good. Increasingly this election represents a test of whether we embrace and will work to realize a truly inclusive, multiracial democracy with liberty and justice for all.

IF YOU EXPECT a column about art, you may have turned to the wrong page. Though I would very much like to be writing about aesthetics, I’m afraid I cannot do so outright. The problem is simple: Our world is on fire, has been for a very long time, and we can no longer afford to avoid the why. Our country looks in the mirror and cannot recognize its face because its self-concept is built on lies. To be an American, it seems, is to be in a state of constant dissociation. Perhaps that is the fine print in our social contract—mandated distance from our inner worlds and the violence we inflict on each other.

But, if we are constantly looking away from ourselves, what are we looking at instead? The answer is, again, simple. We—this “we” primarily composed of white people—have traded a clear vision of reality away for the tawdry allure of images. Put frankly, we worship a portrait of America that has not yet come into being.

When we say the upcoming election is the most consequential election in our lifetime, it is not hyperbole or political spin, but a reflection of just how stark the choices have become and the perilous nature of the crises that our communities, our nation, and our world faces.

We live in the shadow of flags meant to forever hide us, to remind us we don’t belong.

What remains for all who’ve hit rock bottom is the long road to healing.

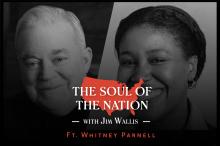

How did white people justify racism for so long in this country? Heather McGhee, the co-chair of Color of Change, the country’s largest online racial justice organization, talks with Rev. Jim Wallis about the legacy of racism in the United States and the lies that allow America’s original sin to be perpetuated to this day.

Before I learned my town’s true history, I cared about racial justice.

Whether their blood cries out from Valdosta Ga., or the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison, their cries cannot go unanswered.

Good Trouble is a timely and deeply moving film, particularly in this moment of national awakening and reckoning around police violence and systemic racism, and as we approach what feels like the most consequential election in my lifetime.

On the 155th observance of Juneteenth, a collective of Black church pastors and theologians released a theological statement to “emphatically repudiate the evil beast of white racism, white supremacy, white superiority and its concomitant and abiding anti-Black violence.”

This history runs through, into, and over my interracial children.

In July 1952, when I was 11 years old, some of my relatives took me to witness the Billy Graham Crusade in Jackson, Miss. Ropes were strung across the athletic field and stands where more than 300,000 people would gather to hear him preach during those hot summer nights. The ropes had one purpose: to keep the crowd segregated by the color of their skin.

I am tired of white colleagues who have ignored the reports of microagressions and outright racism but are now posting black boxes on social media or reaching out to me with an “I love you.” They may mean well but it often feels so little and too late.

White churches need to enter conversations of racial justice with sobriety.

In Exodus, the Egyptians shed innocent blood. Then God made this blood visible for all to see.

Looting is not the story. Murder is the story.

Whitney Parnell, Founder and CEO of Service Never Sleeps, talks with Rev. Jim Wallis in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd about systemic racism, white privilege, and the hope for our collective future.