Racism

PRESIDENT TRUMP “DISCOVERED” this spring that African Americans are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. “Why is it three or four times more so for the black community as opposed to other people?” he asked during a live coronavirus task force briefing in April. Black social media erupted.

One friend wrote, “The white man said it, but we have been screaming this for years.” Another person posted, “Blackness is not a risk factor. Anti-blackness is the comorbidity.”

I began to seriously consider the impact of race on health while becoming a registered nurse. Combating health disparities in the black community eventually brought me to midwifery. As a health care provider, the language of “comorbidity” (two or more chronic health conditions) and “modifiable health risk” (a risk factor for illness that can be lowered by taking an action) has become part of my vocabulary.

Following Trump’s question at the press briefing, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, responded, “When you look at the predisposing conditions that lead to a bad outcome with coronavirus ... they are just those very comorbidities that are unfortunately disproportionately prevalent in the African American population.” A few days later, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Jerome Adams noted that minorities are not more predisposed to infection “biologically or genetically,” but rather they are “socially predisposed” to it.

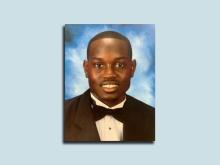

I was never concerned that there could be consequences for crossing a main road that separated our immediate neighborhood from the adjacent one, or that the Confederate flags I passed along my route might be intended as a “no trespassing” sign for people who looked like me. I wasn’t Ahmaud. Scores of childhood friends donned camo and lugged military-style toy rifles from yard to yard as we replayed World War II battles. No one worried a police officer, or a neighborhood vigilante, patrolling our streets would mistake us for a real threat. We weren’t Tamir Rice or Trayvon Martin.

I can remember when it first happened — when my dungeon shook and my chains fell off. I had recently gone through a horrible experience and felt there was nowhere to turn, no one who could give voice to my ache, my pain, and my rage.

The COVID-19 pandemic has now laid bare what is still “acceptable” to white America, including many white churches. The unequal suffering of this plague has been verified by the statistics.

Burton and Dreher share similar aesthetic views about Christianity and the past.

We believe all human beings are made in the “imago dei,” the image and likeness of God — it’s a core tenet of ours and many other faiths. Just as the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed how injustices in our health care and safety net systems stand in stark contrast to that core ideal, so too does any strategy that would negate a people’s votes because of the color of their skin. It is not just a partisan tactic, but rather a denial of their imago dei, a theological, biblical, and spiritual offense to God. Protecting the right to vote affirms the divine imprint and inherent value of all of God’s children.

When will the lives of black people ever matter to America? Black people are tired.

What value is there in circulating a depiction of innocent black death?

How will progressive Christians react to rising anti-Semitism in this pandemic?

In this moment, Chinese and Asian American communities are facing the double stress of having to reckon with the racism and xenophobia they encounter, compounded with having to deal with the virus outbreak itself.

Of course, dirt also tells stories of human triumph and transgression. With one scan from an X-ray fluorescence gun, you can tell whether a soil sample came from Cambridge or Dorchester, based on the amount of lead particulates present. A Ziploc bag full of dirt is also a history of redlining, white flight, and devastating arson, committed by property owners for whom the cost of maintaining the land surpassed the worth of those who called it home. Dirt is an archive of human attitudes toward the nonhuman world — our hubris in thinking ourselves separate from it, though we arose from it, and will inevitably return to it.

With picturesque homes and landscapes, plantations promote a false message of comfort and simplicity. But the people who worked the grounds, managed the home, and fostered their families enjoyed none of the supposed serenity.

Negative social attitudes, such as racism and discrimination, damage the health of those who are targeted by triggering a cascade of aberrant biological responses, including abnormal gene activity.

A racial leveraging of forgiveness followed Amber Guyger’s trial in Dallas.

This challenge to dismantle white supremacy and build a beloved community is one that white Christians need to undertake for the sake of their own obedience to God. Those of us who are white need to realize that this challenge and calling isn't for other people. It isn't for people of color who white people need to help.

During Obama’s second term, less than 50 percent of active federal judges were white men for the first time in American history, according to the Congressional Research Service. In under two years, President Donald Trump has reversed that trend. He has so far successfully appointed 152 individuals to judgeships in the federal circuit and district courts, of which 60 percent are white males. He has also filled two vacancies on the Supreme Court with conservative white males.

A YOUNG LAWYER asks Jesus what he must do “to inherit eternal life.” To which Jesus gives a simple answer: Love God and love your neighbor. There you have it, says Jesus. But the inquisitor asks Jesus a follow-up question: “And who is my neighbor?” (Luke 10:25–37). It’s clear from the context that this lawyer was seeking to diminish or limit the scope of who counted as his neighbor. The tone isn’t one of expanding the reach of loving his neighbor but of restricting it. Jesus answers with the exemplary story of the Good Samaritan in a way that upends expectations and gets to the heart of the question. The lesson of Jesus’ parable is much deeper than the traditional understanding of the Good Samaritan—that Jesus is simply commending the act of reaching out to another in need, as the Samaritan does, as opposed to the priest and Levite in Jesus’ story who famously passed by the man because they were too busy or preoccupied or afraid of being late to an important religious meeting.

But what Jesus is trying to teach us here goes much deeper than simple compassion and service to the needy. The Samaritans were not “good,” as far as the Judeans of Jesus’ day were concerned. They were a despised mixed race, considered half-breeds and foreigners by the Jews. They usually provoked disgust, not admiration. But Jesus chooses the hated “other” as his example of who our neighbor is. Jesus then describes the Samaritan taking actions that show us what it means to be a neighbor as the Samaritan reaches out to someone who was an “other” to him with practical assistance, self-sacrifice, and risk on the dangerous highway of the Jericho Road.

Martin Luther King Jr., in the final sermon of his life, the day before he was assassinated, talked about the dangers of the Jericho Road: “It’s a winding, meandering road. It’s really conducive for ambushing,” King said. “And so the first question that ... the Levite asked was, ‘If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?’ But then the Good Samaritan came by and he reversed the question: ‘If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?’”

Anti-Christ is a very big word, very evocative of our deepest spiritual realties and feelings, and is seldom invoked without controversy. It’s been abused by those promoting bad “end times” and “left behind” theology. But it’s also a profoundly biblical concept, one we must take as seriously in our day as Jesus did in his. Jesus warned his followers to be on the lookout for “pseudo-christs,” those that claimed his name but were far from the true heart of God, and said, “Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven.”

As a result of the political, religious, and moral crises we face today, both the soul of the nation and the integrity of faith are now at stake. This crisis is fundamentally about our chance and our choice of whether those who call themselves Christians are ready to go back to the teachings of Jesus, and whether such a call might be taken up by others beyond the churches. Many of us share a deep hunger for reclaiming Jesus instead of falling into more political polarization — we want theology to trump politics.

Though Juarez is known as a center of cartel- and smuggling-related violence, El Paso is rated on various websites as one of the safest cities in America and among the best places to retire or raise a family. According to KVIA, a local ABC affiliate, it averages 16 murders a year.