mass incarceration

MY DREAMS ARE dominated by repairing the harms of mass incarceration. I dream of a future that includes decarceration and prison closures, one where Black people aren’t at risk of fatal police interactions. I dream of a future for Black people where public safety isn’t defined by arrests and lengthy prison terms. My Black future dreams are radical in the context of America. If my dreams were currently possible, the anti-Black through line that characterizes the nation’s public safety strategy would look a lot different.

Violent crime rates tripled between 1965 and 1990 in the United States, Germany, and Finland. Yet, countries have the policies and prison populations they choose. German politicians chose to hold the imprisonment rate flat. Finnish politicians chose to substantially reduce their imprisonment rate. American politicians chose to lengthen prison terms and send more people to prison. When migrant populations, some from the Global South, began moving into Germany and Finland, they were soon overrepresented in the prisons, incarcerated at twice the rate of citizens. Ethnic disparities and anti-Blackness drive incarceration policies everywhere.

Even in the context of increases in crime, the United States could choose another way. Public safety strategies could be centered on undoing the anti-Black practices that dominate criminal legal policies. Solutions must reduce the number of people imprisoned and strengthen communities rather than disappearing Black people from families and loved ones.

Jesus’ “mission statement” when he begins his public ministry in Galilee includes a promise of liberation and release for those who are incarcerated. While the New Testament context of “captivity” wasn’t entirely the same as modern imprisonment, Jesus’ promise aligns liberation of prisoners with healing and good news for the poor and oppressed. Taking Jesus’ words in this text seriously forces us to ask: If God’s reign is characterized by freedom for prisoners, why are we supporting incarceration now?

IN THIS MONTH'S cover feature, Lydia Wylie-Kellermann wrestles with one of the central dilemmas of parenting: the tension between protecting our children and empowering them for action. That tension is made more pointed, and the stakes elevated, by the crises we face—including, perhaps most urgently, climate change. Though I imagine that balance has been one of the more challenging aspects of raising children since the invention of parenthood.

AMERICAN HYPERPOLICING and mass incarceration are products of 50 years of cynical politics, vicious economics, and unconscionable racism—as the mass uprising in the wake of George Floyd’s killing has brought into ever clearer focus. Across the country, organizers on the ground are pushing to defund the police. Meanwhile, for people Left, Right, and center, “ending mass incarceration” has become a standard political talking point. But what precisely would “ending mass incarceration” entail?

Imagine that tomorrow we were to enact the most radical reforms to the prison system conceivable—reforms tailored to mass incarceration’s political, economic, and racial dimensions. First, to scale down the war on drugs, we could pardon every person in state and federal custody who is incarcerated solely on the basis of a nonviolent drug offense. Second, to stop caging people simply because they are poor, we could release every pretrial defendant who is sitting in jail solely because they are unable to make bail. Third, to end what’s been called the New Jim Crow, imagine if every Black state and federal prisoner—who constitute one-third of those in prison—were freed, regardless of whether they were guilty of a crime. By committing to these three measures (which, needless to say, aren’t being seriously considered in Washington or in any state capital), the U.S. would reduce its prison population by more than 50 percent, to a tick over 1 million people. In the COVID-era especially, when prisons and jails are incubators of the virus, many lives would be saved. Families would be reunited. Much suffering would be forestalled.

What such a robust menu of reforms would not meaningfully do, however, is end mass incarceration. Even at half its current size, the U.S. incarceration rate would remain three times that of France, four times that of Germany, and similar degrees in excess of where it was for the first three-quarters of the 20th century. Given the massiveness of the American carceral edifice, we cannot reform our way out of mass incarceration. Nor does the reformist impulse address the crux of the problem.

“We have seen many reported examples of abuse within our private prison population,” Cardin said at a briefing on private prisons. “We know that there are problems there, but we don’t have the information we need because they are exempt from the same requirements prisons run by the government need to comply with.”

If we want to enact justice in any situation, we must listen to the voices of those directly impacted by the injustice. Those of us who served time on Rikers Island know firsthand why it has to close. Any movement for justice that is not led by directly impacted people is charity, at best, but it is not biblical justice. Biblical justice empowers, while charity can disempower if it is not coupled with justice.

This week, a U.S. House Judiciary subcommittee held a hearing on women in the criminal justice system. While women only make up 7 percent of the prison population, the incarceration rate for women has increased at twice the pace as the incarceration rate for men since 1980, disproportionately impacting women of color.

In the United States, we count drug overdoses per 100,000, not per million. The comparable numbers are 6 per million in Portugal, 21.3 per million for the European Union, and 217 per million in the United States.

Unless the money that will be made from marijuana’s federal legalization is used for robust community reinvestment in affected residential communities across America, it fails the moral litmus test of social justice and pumps oxygen into racial wealth disparities. Without this reinvestment, America will once again be blowing smoke into the face of those who have historically been most victimized by the criminalization of marijuana. The abovementioned federal legalization proposal includes the development of a community reinvestment fund to specifically benefit communities most ravished by the marijuana ban, and the decades-long failed war on drugs. The architects of the bill outlined some potential funding areas: job training, post-incarceration and expungement services, public libraries and community centers, youth programming, and health education.

The continued demise of faith in this nation’s criminal justice system, elected officials, and government will increase wherever injustice is maintained in the name of “doing just enough”. If America is truly to be one nation, it must address and correct its patterns of injustice and persistent denials of full personhood for those who belong in this country and society.

I watched Ava DuVernay’s Netflix series When They See Us and found myself angered by the people and systems that had a role in the incarceration of five innocent boys. The Central Park Five, Raymond Santana, Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Yusef Saalam, and Korey Wise, were wrongfully convicted and later exonerated of a variety of charges related to the rape and assault of a white female jogger in 1989. While the series itself honors the stories of the Central Park Five, in choosing to title the series When They See Us, DuVernay invites us into a broader conversation on the criminalization and mass incarceration of young boys and girls of color, and challenges us to define our own role within this system.

Inextinguishable Spirit

“Black faith still can’t be washed away” Solange sings in her album When I Get Home. The ambient work pays homage to her Houston roots while exploring themes of blackness and spirituality. Synth, syncopated drums, smooth vocals, and experimental time signatures form a liberating fusion of sound. Saint Records/Columbia

STEVE KLAWONN, pastor of Prince of Peace Lutheran Church in Evansdale, Iowa, was near the end of a seven-year church redesign when he scoured the internet for new church furniture—with no promising leads.

“Needless to say, church furniture prices tend to be pretty high,” he said.

In a climate where church attendance is declining and houses of worship are looking for creative ways to stay in operation, solid wood pulpits and lecterns are expensive investments. In nearby Humbolt, family-owned Gunder Church Furniture sells a winged pulpit for $1,546; a matching lectern goes for $1,078. Klawonn liked the idea of choosing an in-state manufacturer, but affordability was key.

CNN commentator Van Jones, co-founder of #cut50, an initiative to reduce the prison population, moderated a Saturday morning panel at the annual winter meeting of governors. Jones worked with the Trump administration to rally support for the First Step Act, which the president signed into law in December. Jones called Republican Gov. Phil Bryant “our secret weapon” in convincing Donald Trump to support the criminal justice reform bill.

And I can’t help but think about my friends on “life” row who live daily in that space. They know that their execution dates can be set at any moment, but they also know that they are alive now and have to live into as much of the fullness of the day as they possibly can. It can be difficult, at times, to sit in the liminal space with my friends, as I never know which they will choose — will they choose life or will they choose death to discuss? And the truth is that they pick both. They need to process their death while they are living. And they have to process their living while they know they face a certain death.

My friends on the row want to end up like our psalmist. They need to be set free from the prison that they are in — the prison in their minds which holds them captive and will not let them go. A lot of my friends have had traumatic childhoods, leading them to be hypervigilant. They have trained their brains to listen for every little sound in order to keep themselves safe. That same hypervigilance is pure torture inside a prison where the cacophony of sounds demands their on-going attention. They deal with the replaying of scenes in their lives that were painful. Therefore heir minds do not know what it means to be at peace. They desperately need to be free from the prison in their mind.

This bill is very aptly named. The First Step Act is just that and no better — a first, extremely modest step on what will need to be a much longer path of extensive reforms to a deeply broken system. That system can best be understood, as Bryan Stevenson and others have so clearly pointed out, as the direct evolution of slavery into the system of mass incarceration.

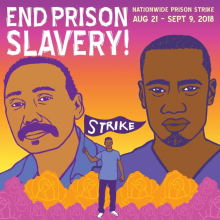

From Florida to California, imprisoned activists are organizing work stoppages, boycotting prison commissaries, and going on hunger strikes to draw attention to injustice in the U.S. prison system. Faith groups such as Christians for Socialism and The Friendly Fire Collective are supporting these prisoners as they hold a 19-day strike protesting what they call “prison slavery.” They see fighting for justice alongside prisoners as an important expression of their faith.

AMERICA HAS A CRISIS of mass incarceration, and it has little to do with crime rates. The system is broken: America imprisons more of its citizens than any other nation in the world. Even though the United States contains just 5 percent of the world’s population, the nation has nearly 25 percent of the world’s prisoners. At every point, from the laws on sentencing to policing practices and health conditions in prisons, impersonal forces exact a very personal toll on incarcerated persons and their families.

Many citizens have started to work on solutions by raising awareness, legalizing drugs such as marijuana, and passing laws that require police officers to wear body cameras. But one critical function of our legal system has received too little attention from Christians and the rest of the public: local prosecutors.

Local prosecutors, or district attorneys, as they are formally known, hold enormous influence. These 2,400 individuals nationwide have the authority to determine when, how, and how severely to charge a person with a crime. They help determine when someone goes home and when someone goes to prison for decades. Their decisions could mean the difference between an innocent person going free or going on death row.

I first became aware of the issues related to local prosecutors while attending a lecture at the University of Mississippi in fall 2017. I was there to hear James Forman Jr. talk about his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America, which describes how black Americans, for complex reasons, supported the “tough on crime” policies that led to mass incarceration. During the Q&A that followed Forman’s lecture, one student asked Forman how nonlawyers could join in the effort to reform the criminal justice system. A part of Forman’s response remained with me.

“Get involved in local races,” he said. “Local prosecutors are the most powerful people in the system, but nobody votes in these races.”

TWO WHITE TEENAGERS were recently convicted of spraying racist graffiti on a historic black school in northern Virginia. Their somewhat unusual sentence: Read from a list of 35 books, one a month for a year, and submit a report on all 12 to their parole officers. The booklist included Cry the Beloved Country, by Alan Paton,To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, by Maya Angelou, Night, by Elie Wiesel, and other classics.

The remarkable feature of this sentence was how it clashed conceptually with the customary default question that suffuses our judicial system: How long a prison sentence does the crime deserve?

A strange mathematics is at work in our criminal justice system: For every crime, a matching time in prison. Translating the crime of racist graffiti into reading books that might reform the minds of two teenagers makes a certain rational match with the crime. Putting them in prison for five years is no match at all.