mass incarceration

I AM A CHRISTIAN. That means that I serve a savior who told us he came to free prisoners. At the same time, I live in a nation with more than 2 million prisoners, more than any country in the world.

I am also an affluent white person living in a country that unequally and selectively jails people of color and poor people. And I don’t just live in this country, I help govern it.

As a state representative in Michigan, I am responsible for this situation. The government directly chooses who goes to jail and who doesn’t. Of course, since our democracy practices government “of the people,” that makes all of us responsible for government actions.

How should Christians who are also citizens take action for justice in our law enforcement system? Responding to mass incarceration as Christians can seem daunting, but there are obvious places to begin. One of the clearest places our current system fails the test of equal treatment under the law is in the detention or release of those accused of, but not convicted of, a crime.

Another issue that we know: In a number of states, pregnant women, when they give birth in the midst of their sentences, they’re forced to be shackled to a gurney in the midst of their delivery process. We know being born into that stress-induced state has irreversible cognitive impacts on the child, but we still haven’t changed the law in light of that.

IN THE SECOND century, Jesus’ followers were not a reputable bunch. Most people had probably never heard of Christians, but some knew the rumors: They worshipped a crucified criminal, ate flesh and blood, and obstinately refused to sacrifice to the gods. And they were notorious for hanging around prisons.

This is partly because many early Christians ended up in prison themselves. Jesus did. Peter did. Paul did. Ignatius of Antioch did.

But Christians were also known for showing up at prisons voluntarily. In one of the earliest surviving references to the Christian movement by an outsider, the second-century writer Lucian, who thought followers of Christ were laughably ignorant and naive, mocks them for the support they gave an imprisoned Christian leader named Peregrinus. Lucian describes widows and orphans loitering around the prison while their leaders bribe the jailers to get inside, bringing Peregrinus food and encouraging him with the scriptures. “It’s incredible how quickly they respond in such situations,” he remarks. “They get to work immediately, and spare nothing.”

“The Church has both the unique ability and unparalleled capacity to confront the staggering crisis of crime and incarceration in America,” the declaration reads, “and to respond with restorative solutions for communities, victims, and individuals responsible for crime.”

In a nation founded on violence, how are we to respond when young indigenous people are beaten to death by police or young black men are shot in the front seat of their cars? What do we do when young Muslim women are assaulted on the way to say prayers with their community? In an attempt to protect ourselves from violence, we actually bring violence to our schools and neighborhoods, because we live a gospel of violence perpetuated over time by our attitudes of hate and racism toward one another.

In an age when both explicit and implicit biases are becoming legitimate justifications to curse the image of God, it is time for the church in the U.S. to face itself. It is time to repair the broken fabric of our nation. It is time to interrogate the stories we tell our selves about ourselves by immersing ourselves in the stories of the other.

Faith leaders across the country have opposed Sessions’ confirmation as U.S. attorney general with petitions and statements, calling him unfit to make decisions that are helpful to communities of color across the U.S — especially around prison sentencing for black people.

Paschal pardon here exemplifies a miscarriage of justice for one of the prisoners. The custom condemns Jesus, whose guilt is dubious. Ultimately, Jesus divinely conquers the unjust system at hand when he walks freely among his disciples in the flesh, three days after he is crucified as a criminal. But the possibility of a triumphant erasure of crime in the U.S. is limited. Constitutionally, the president can offer clemency — or “leniency” — for any federal offense, aside from cases involved with impeachment, by two methods: commute, which lessens the sentence but retains civil restrictions like the loss of the right to vote, or pardon, which eliminates the sentence entirely.

While they told Moses that, “All the words that the Lord has spoken we will do” (Exodus 24:3), in the end they turned to idols and broke God’s laws. By the time we get to First Samuel, we hear the people clamoring for an earthly king so they could be like other nations (1 Samuel 8:4-22). They thought life would be better if they shook up their system of government, so they ditched the judges and looked for an outsider. In the end, they got exactly what they asked for – a king named Saul who was wicked and moody and paranoid.

Outside of his role in our family, my grandfather played three roles in life that were dear to him: die-hard Mets fan, deacon in his church, never-miss-an-election voter. He was so unbelievably clear in his intention about voting, and perfectly committed to voting. He made that connection between faith and action.

And in his way, he lived out something I think about all the time: how to make our presence in the world powerful enough to change it.

We can no longer turn a blind eye to what profit margins do to prisoners, more and more of whom are from vulnerable populations. We are called to dismantle the corrupt justice system of mass incarceration. Ending private prison profiteering is a critical step towards restorative justice for all.

The Justice Department’s move to phase out private federal prisons brings a welcome end to a moral and political crisis that has tested the very foundations of our democracy. It is a historic and courageous leap toward a more fair and equitable system of justice in our nation.

In a memo announced Thursday, the Justice Department announced it plans to end using private prisons in the United States. As reported in the Washington Post, Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates will instruct, “officials to either decline to renew the contracts for private prison operators when they expire or “substantially reduce” the contracts’ scope.”

Union Theological Seminary in New York City will no longer ask applicants to check a box indicating whether they have a criminal history, reports TheBlaze.

Union also signed onto the White House’s “Fair Chance Pledge,” which encourages businesses and schools to eliminate unnecessary barriers to people with criminal records. Many of the other institutions who have signed on have similarly “banned the box” on their applications.

How could I not? How could I benefit from the messed-up grace of God that allows me to be seen by God on high not as a horrible sinner full and capable of every last deadly sin but as a beloved child and not see others differently myself? It’s messed up, but it’s true.

It’s impossible to laugh, pray, and sing old gospel songs with men who’ve raped and murdered, who’ve sold drugs to children, carjacked strangers, shot girlfriends, buried bodies in woods and not see grace.

I could not look at lines of incarcerated men, ready for a day’s work under the gun (literally), and not shudder at past (and sometimes present) atrocities and injustices. And yet, I could only hope for redemption for this land that no longer grows cotton and for these men who no longer have freedom.

And there’s no way I could rub puppies’ tummies while talking to an inmate-cowboy about dogs, to hear him tell me lots of guys here are like pit bulls because they think they’re tough, but that those guys don’t know—“They’re just silly snuggle bugs,” he says—and me not feel the peace of Christ descend.

I don’t know why. I don’t know how. I just know it’s true: When we visit prisoners, we visit Christ. All during my time in Angola, I saw Jesus everywhere.

President Obama plans on June 3 to commute the sentences of 42 federal prisoners, 20 of whom have life sentences, according to The Huffington Post.

Obama has used his commutation power much more often than past presidents — his 348 commutations so far surpass the total issued by the past seven combined.

Speaker of the House Paul Ryan has said repeatedly that he isn’t running for president, but that hasn’t stopped him from making numerous public appearances to talk about his vision for the Republican Party and the United States.

More than five million children in the U.S. have or have had a parent imprisoned. And the consequences can be devastating.

According to “A Shared Sentence,” a new report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, “Having a parent incarcerated is a stressful, traumatic experience of the same magnitude as abuse, domestic violence, and divorce.”

I was always going to make a film about prisons, but from the outside of the prison itself. I wanted to challenge the alienation we feel by seeing prisons simply as buildings we have no relationship to. I had originally thought I was just going to set it in one city. For example, when you look at the prison population in New York State, a lot of those prisoners come from a small section of neighborhoods, and I was originally thinking of setting the film in those places.

I ended up going on a longer journey, with a goal to disrupt the identity of these areas we think of as “free,” to reveal how deeply prisons influence our lives in all spaces.

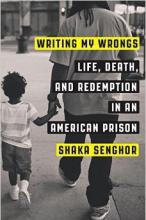

MY SON WAS 10 YEARS, and the sight of an envelope addressed in his squiggly handwriting filled my spirit with joy. But as I tore open the envelope and began reading, I saw that this letter was different from the ones he had sent before.

In the top right-hand corner, Li’l Jay had written in big, capital letters:

MY MOM TOLD ME WHY YOU’RE IN JAIL, BECAUSE OF MURDER! DON’T KILL DAD PLEASE THAT IS A SIN. JESUS WATCHES WHAT YOU DO. PRAY TO HIM.

I stared at the small paragraph for what felt like hours. My body trembled violently, and everything inside of me threatened to break in half. For the first time in my incarceration, I was hit with the truth that my son would grow up to see me as a murderer.

I don’t know why I hadn’t thought about it before. It’s not that I was planning to hide my past from my son—it’s just that I thought I would be able to sit down and explain it to him when I felt he was mature enough for the conversation. But as I read Li’l Jay’s words, reality kicked me in the gut, and the pain of not knowing what to say spread through my body like cancer.

I didn’t know the context of the conversation that he had with his mother, so I wasn’t sure how to respond. The only thing I was sure of was that I had to do everything in my power to turn my life around. It was the only way I could show my son that I was not a monster.

His letter continued:

Dear daddy, I wonder how you’re doing in there. I’m doing fine. When I think about you, it makes me feel sad with no daddy around to wake me up and go work out and be strong like you. I have to do it all by myself. It bothers me the way I miss you. I pray and pray one day my prayer may come true and we’ll be together 4 life. It’s the anger in my heart that hurts me most without a dad in the house. My mama said I am the man of the house. She tells me I have to take over the anger so I won’t be in jail.