mass incarceration

Only in America can you have a huge segment of society become obsessed with a cultural sensation that revolves around the themes of unjust incarceration, a biased legal system, corrupt law enforcement, and a judicial process that disproportionately targets the poor and underrepresented, and simultaneously have the majority of this exact same group not understand the reality of racial injustice.

People of color in the United States, particularly young black men, are burdened with a presumption of guilt and dangerousness. Some version of what happened to me has been unfairly experienced by hundreds of thousands of black and brown people throughout this country. As a consequence of our nation’s historical failure to address the legacy of racial inequality, the presumption of guilt and the racial narrative that created it have significantly shaped every institution in American society, especially our criminal justice system.

State officials in New York are reforming their policy of keeping people convicted of non-violent offenses in solitary confinement. Some hail the decision; others, including corrections officers, object, saying that solitary confinement is necessary to maintain control, and they say that keeping an individual in solitary confinement is not inhumane.

Tell that, though, to innocent people in prison, wrongly convicted, who find themselves in solitary confinement without hope of ever getting out.

A new study from the Vera Institute of Justice suggests that mass incarceration, typically focused in urban centers, is growing fastest in suburbs and rural areas.

The U.S. already has a massive imprisonment problem — despite having 4 percent of the world’s population, the U.S. has 25 percent of the world’s prisoners. And now, the problem is spreading beyond cities. In 2014, densely-populated counties had 271 inmates in jail per 100,000 people, whereas sparsely-populated counties had 446 inmates per 100,000 people — nearly double the amount.

EARLY ONE SUNDAY MORNING, I drive to the Durham Correctional Center to pick up Greg. He’s spent the past 16 months at a state prison down east, working overtime in the kitchen so he could get out six weeks early. A few days ago, the Department of Corrections transferred him to this local minimum-security facility. Greg knows the place well. He’s walked out of here more times than he can count.

“Feel good to be out?” I ask as we walk through the gate of the chain-link fence, nodding goodbye to the guards. “You know it does,” Greg says, his back straight and his eyes fixed on the horizon. He’s relishing this taste of freedom.

But Greg knows this pleasure is fleeting. As good as it might feel to walk through the gate and hop in a car, leaving prison doesn’t mean you get to leave this part of your life behind.

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, more than 2.4 million Americans are locked behind bars (and 12 million cycle through local jails each year). At any given time, some 6 million Americans are caught up in the criminal justice system—if not behind bars, then checking in with a parole officer who can carry them back to jail for the smallest of transgressions. Like Greg, a disproportionate number of those impacted by the U.S. criminal justice system are African American.

Even if you walk out of the gate like Greg, time served, you still have to deal with the debts that ruined your credit while you were locked away. You still have to rebuild relationships that were cut off because you spent the past decade behind bars. You still have to check the box on almost every job application that says you’re a convicted felon.

I live in a home named Rutba House, where we have opened our doors to friends like Greg who are coming home from prison. Doing so has helped me see that our country’s original sin of race-based slavery has shifted its shape again in the 21st century. As the Black Lives Matter movement has tried to make clear on America’s streets, race still matters. But in light of the fact that African Americans are incarcerated at nearly six times the rate of whites, we cannot understand race in America today without understanding prisons.

Pell grants are otherwise open to the vast majority of students enrolled in college. The Department of Education claims that age, race, and field of study don’t compromise eligibility. Yet the Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that black men constitute the highest rate of imprisonment by 3.8 to 10.5 times that of white men. And in the U.S., wide gaps persist in the educational attainment of black men.

Conventional data sources do not always link this growing education gap to prison rates for one main reason — statistics don’t include those who are incarcerated. This omission skews numbers around racial disparities in educational achievement by over 40 percent for black men.

The bottom line is that African American men are not only disproportionately overrepresented in our prison system; they are also disproportionately undereducated.

Given these numbers, we ought to be raising an obvious question: Can the Department of Education honestly claim that Pell grants are color blind?

The American Civil Liberties Union of Ohio released Nov. 9 the first comprehensive study of the practice of charging people in jail for their time there, also known as “pay-to-stay” policies, reports the BBC.

The study revealed that some inmates have debts of up to $35,000, although the BBC found evidence that one man in Marion, Ohio owes $50,000 in pay-to-stay debt.

Pay-to-stay is not limited to the state of Ohio, however. With the exceptions of Hawaii and the District of Columbia, every state in the U.S. has a law authorizing the practice.

President Obama announced Nov. 2 a new executive order to reduce hiring discrimination against former convicts, according to MSNBC.

Applicants for positions in the federal government will no longer be required to check a box on their applications if they have a criminal record.

1. 9 Ways We Can Make Social Justice Movements Less Elitist and More Accessible

"After a few weeks of feeling confused and invisible, I decided that I just wasn't smart enough to be an activist."

2. WATCH: Obama Condemns 'Routine' of Mass Shootings, Says U.S. Has Become Numb

"As I said just a few months ago, and I said a few months before that, and I said each time we see one of these mass shootings, our thoughts and prayers are not enough."

3. French Catholics Take in Refugee Family Seeking a 'Normal Life'

"The local effort is part of a national Catholic network that connects homeless asylum seekers with families willing to take them in."

Next week, the conversation will change in America. All the media attention recently given to political figures will now shift to a moral leader who is changing the global public discussion about what is compassionate, just, good, and right -- and Christian.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is at it again — this time in The Atlantic’s newly released October 2015 issue.

In “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” Coates wrestles with the dark underside of criminal justice in the United States. As he is apt to do, Coates effortlessly teases out the connections between our nation’s present situation — unimaginably high rates of incarceration, particularly among black Americans — and our historical plundering of the black community. Conceptually nuanced, historically rigorous, and artfully crafted, “Family” is a success on every level.

Yet soon after Coates’ piece was published, Thabiti Anyabwile issued a cogent response decrying Coates’ apparent hopelessness. Anyabwile’s response highlighted fundamental differences in the two writers’ worldviews. Physical bodies and the violence they endure, not theologies, are afforded primacy of place in Coates’ analyses.

In this sense, Anyabwile serves as an interesting counterweight to Coates. A pastor at Capitol Hill Baptist Church and council member with The Gospel Coalition, Anyabwile is unabashedly Christian. The “comforting narrative of divine law,” eschewed so often by Coates, is one in which Christians like Anyabwile and myself regularly take solace.

The Forgiveness

By Steven

I forgive my dad for walking out on his only son

I forgive the people who think they get over

When they assume that I’m dumb

I forgive life for dealing me this hand

I forgive my inner boy for not becoming a man

I forgive the man who bumped me

Because he couldn’t see

I forgive ...

But I can’t forgive everything

Because I’ve yet to forgive me ...

Steven is an active member of the Free Minds Book Club.

1. Death of a Young Black Journalist

“The most basic instinct of a local reporter is to take the importance of her neighbors as a given. In a community like Anacostia—where more than ninety per cent of residents are African-American, one in two kids lives below the poverty line, and incarceration and unemployment rates are among the nation’s highest—this is another way of saying that black lives matter.”

2. Dear NBC, BBC, CNN, and Others: Mugshots Are for Criminals, Not for Their Victims

“Using a mugshot that has no relevance to the circumstances in which Sam DuBose was killed—up against a fully-uniformed photo of his accused killer—suggests that DuBose did something criminal to instigate the cop in his shooting. As yesterday’s grand jury decision confirms, this is blatantly not true. It warps the real story: a cop who allegedly killed an innocent man for no good reason.”

3. We Need to Talk About Feminism and Vocal Fry

“The clash here is not between anti-feminists and feminists. At its heart, the conflict over vocal fry is a clashing of feminist ideologies. … Wolf suggests that young women’s voices aren’t authoritative enough, and implies that they’re somehow squandering all the hard feminist work that came before them. But what’s really happening is a generational shift, both in feminism and in the workplace.”

ON A COOL NIGHT in spring 2006, I knelt with a half-dozen friends on the driveway of North Carolina’s maximum-security prison. When officers came to inform us we were trespassing, we asked if they would join us in prayer against the scheduled execution of Willie Brown. Though one officer thanked us for doing what he could not, we were arrested and carried off to the county jail. Willie Brown died early the next morning.

But this isn’t an article about the death penalty.

At the county jail that evening nearly a decade ago, I was fingerprinted, strip-searched, dressed in an orange jumpsuit, and processed into the general population of an overcrowded cell block. When I walked onto the block, I was greeted almost immediately by a 20-something African-American man who asked me, “What the hell are you doing here?” As I summarized the events of the previous evening that had led to my arrest, he decided I was teachable. “You wanna know how I knew you weren’t supposed to be here?” he asked. “’Cause everybody else in here I knew before they got here. We’re all from the same hood.”

“They only kill people like us,” my teacher at the county jail told me that day. “The train that ends at death row starts here.”

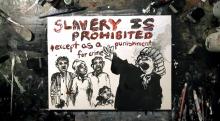

A new video developed by artist Molly Crabapple and the Equal Justice Initiative shows exactly how slavery paved the way for our current system of mass incarceration.

In particular, the video highlights the horror of the domestic slave trade, tracing the development of an elaborate mythology of racial difference — a mythology that once perpetuated slavery and now sustains mass incarceration.

“In many former slave states, slavery did not end. It simply evolved,” says narrator Bryan Stevenson, who directs the Equal Justice Initiative.

Molly Crabapple, known for her artistic contributions to Occupy Wall Street, creates videos combining the fast-paced style of dry-erase animation with the intricate watercolors of an award-winning artist.

One in thirty-one. That’s how many Americans are in in jail, in prison, on probation, or on parole. In the U.S., our incarceration rate is 10 times higher than that of other countries while our actual crime rate is lower than those same countries. Citing a 600% increase in the prison population since the 1960’s, with no correlating increase in crime, Michelle Alexander has called mass incarceration “the new Jim Crow.” When people of color represent 30% of the U.S. population, but 60% of those incarcerated, we are in league with David, staring at a towering giant, armed with a prayer and a handful of stones.

While the work before us is daunting, people of faith are called to fight giants. The Spirit who we remember in Pentecost, the Spirit who set the world on fire, has trusted us with this work. We are giant slayers, by God’s grace. For this reason, it is fitting that we revisit the story of the first giant slayer, a young boy who tended sheep and fought off bears and lions.

When we discuss the gospel of Jesus Christ, we realize that it is a revolutionary message asking us to love our enemies, to do good to those who curse us, and even harder, to turn the other cheek. The gospel is going beyond that. It is asking us to receive, stand, advocate for the poor, incarcerated, and those living in the margins who have been pushed out by the institutions of our society. Jesus took many risks at times during his ministry, and when he started turning over tables and exposing the priests’ racket of selling sacrifices, it did not work out so well for him.

I’m not asking people to go and get themselves killed, but just ask yourself, “How much of the gospel am I willing to perform?”

It was a devastating weekend for black people in America.

On Friday, a white police officer pulled his gun at a pool party and assaulted a 15-year old black girl who cried for her mom in McKinney, Texas. On Saturday, a young black man committed suicide in his parents’ home in the Bronx after being held without trial at Rikers Island for three years (nearly two in solitary confinement), accused of stealing a backpack — a charge that prosecutors ultimately dropped. On Sunday evening, hotel security officers profiled four young black organizers from Baltimore in the lobby of the Congress Plaza Hotel at the conclusion of The Justice Conference.

The fight for the preservation of black and brown lives, that took unexpectedly deep roots in Ferguson and has now spread across nations, was a fight many of our students quickly came to lead, and folks like me have followed.

But many of these young people are not Christian, and frankly, the perception that local congregations lackadaisically approached this movement before it became a national headline — and brought a healthy, condescending dose of respectability politics and patriarchy along with their eventual involvement — is not making most of the millennial set excited about the prospects of salvation.

But local faith leaders like Rev. Traci Blackmon and Rev. Starsky Wilson, and others raised in faith like my friend Rich McClure and me, have clung to the radical example of Christ that guides our collective and individual action.

MY GREAT-GRANDMOTHER, Elizabeth “Lizzie” Johnson, was born in 1890 in Camden, S.C., with a different last name from all the other people in her household. Three generations later, we have no idea where the name Johnson came from.

Lizzie grew up working plantation land owned by her grandmother, Lea Ballard. Lea received the land in the wake of the Civil War: We don’t know how or why, though one theory speculates that Lea, who was listed as a 42-year-old mulatto widow on the 1880 U.S. Census, may have been the daughter of her slave owner. He may have given the land to her after the Civil War. We don’t know. We only know that Lea owned it, that she had 17 children who worked that land, according to family lore, and that the city of Camden eventually stole the land from her by the power of eminent domain. This we know from records I hold in my possession.

Lizzie married a railroad man named Charles Jenkins. Lizzie and Charles had three children; Charles later died in a railroad accident. Lizzie had a choice: endure the brutality of the Jim Crow South alone with three kids, or move with the stream of black bodies migrating north. Lizzie migrated to Washington, D.C., and, eventually, to Philadelphia and took her lightest-skinned child with her.