Culture Watch

A FEW SUNDAYS ago, my partner Greg and I made a pot of chili for our community’s weekly dinner. The New York Times recipe said to add orange juice to the chili, letting it simmer and froth among the chopped onion, garlic, and butter. Then we mixed in the thick, tangy sauce from adobo chili peppers with black beans and sweet potatoes and corn, zipped with lime juice. It was rich, spicy, generous—brightened with the sun.

Lately I’ve had fun trying to write about food, playing with how I’d describe a certain taste, smell, or texture. I’ve been inspired by reading M.F.K. Fisher, who wrote essays about food starting in the late 1930s. She wrote gorgeous prose embedded with care for the human heart, for its loneliness and sadness and hope. In her 1937 essay “Borderland,” she writes about how each of us has our own private food pleasure—hers was warming sections of a tangerine on a radiator in the winter, which she describes while watching soldiers in Strasbourg march along the Rhine, the horrors of war closing in.

IN A PERENNIALLY timely 2014 article about the lessons she learned from her experience with trauma, Catherine Woodiwiss wrote, “Trauma is a disfiguring, lonely time even when surrounded in love; to suffer through trauma alone is unbearable.” We need people around us when we’re suffering, if only to know that they’re there to call on when we need something.

When my trauma and anxiety journey started in 2016, I quickly learned that putting up a front of “Everything’s fine!” only made things worse. It was humbling to admit I needed support. It was empowering to realize people wanted to help. I knew that someday, when I felt better (and I would feel better), I would return the favor.

The film Sorry, Baby, from writer-director Eva Victor, is the most accurate depiction I’ve seen of how trauma stays in your mind and body and what it takes to reach a place of stability. After Victor’s character, Agnes, experiences sexual assault, she relies on the help of close friends and a neighbor, and a stranger’s kindness, to help her through the three-year period that follows.

MY FIRST EXPOSURE to writer Lamorna Ash was the thumbnail image for an interview on YouTube, giant text emblazoning her face with the words “The Case for Christianity.” I must admit, I was skeptical. Granted, I am a Christian who has certainly “made the case” for the profound reality of Jesus of Nazareth now and again—but recently, apologetic arguments and “hardened atheist turned Christian” testimonials have left a sour taste in my mouth.

Perhaps it’s the way that media in that sphere tends to be loaded with culture warrior “Christian Apologist DESTROYS Atheist Snowflake” language. Maybe it’s that, frequently, the case for Christianity actually tends to be the case for Western dominance, whiteness, and heteronormativity. Or maybe it’s even simpler than that: Often, the sheer dogmatic certainty with which these “convert influencers” tend to speak just doesn’t feel honest. Either way, as a queer believer, the genre usually feels out of step with my daily walk.

Nevertheless, I decided to give this particular interview a listen—and Lamorna Ash was nothing like what I’d anticipated. A young and openly queer British woman with a lyrical voice and a heart for Palestine and trans people? This was not the person I’d traditionally expected to make the “case for Christianity.”

COLOR HAS LONG fascinated me. I spend days or weeks debating color choices for knitting and art projects. As a kid, I loved mail-order catalogues for their distinctively named palettes. My shelves teemed with books containing facts about color — names for various shades, how ancient pigments were made (crushed insects, plant extracts, and sea snail secretions), and the meanings of colors in different cultures. Highly conscious of racial differences, I found this last topic compelling. I would match my favorite color that week (it changed constantly) to the meanings provided and see where my tastes aligned.

While I recall few details — such as white is a color for mourning in Japan — what I remember, unfailingly, is absence. Each time I enacted this color-play-as-identification, I imagined my way into a past, land, and set of values other than my own. Because, as with most Western maps of world cultures then and now, the cultural diversity of Africa and Afro-diasporic peoples was not represented.

Imani Perry’s latest book shows this absence to be a speaking one.

PICTURE THIS: A man they call Soccer Moses is descending a set of stadium stairs, parting not the Red Sea but a crowd of Nashville soccer junkies. As he reaches the bottom of the stairs, he puts on a Gibson guitar and performs a celebratory riff, which is a tradition for the Nashville Soccer Club, a Major League Soccer team. As Soccer Moses shreds his guitar, fans surround him and wave signs, scarves, and a Pride flag. One of the many differences between the biblical Moses and Soccer Moses is evident in this scene. Biblical Moses sought to prevent revelry (Exodus 32:18-19); Soccer Moses lives to promote it.

Soccer Moses is the unofficial team mascot for Nashville SC. Why, if Nashville SC is not connected to religion in any way, has a zealous fan taken it upon himself to dress up like Moses and become the team’s unofficial ambassador? Well, to understand that you first need to know the identity of the man donning the wig, fake beard, and flowing garments.

“ON EARTH AS it is in heaven,” wasn’t simply a prayer for the Shakers, a small Protestant sect that practiced communal living and peaked in the mid-19th century: It was the bedrock of their lives. In the mid-1800s, Shaker Sarah Bates depicted this collision of heaven with earth in “Wings of Holy Wisdom, Wings of the Heavenly Father.” In cobalt and inky blues, she drew churning stars and slivered moons, holy scrolls and books cracked open by birds, God’s hand reaching through dark heavens, trumpets and swords among unfurling flowers.

The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Coming originated in England in 1747 and were guided to America in 1774 by Mother Ann Lee, an illiterate factory worker who became the community’s charismatic leader. Their ecstatic dancing during worship led some to call them “shaking Quakers,” later shortened to “Shakers.” Lee preached ideals such as pacifism and gender and racial equality, and in the new communities in America, she introduced celibacy and no private property. Lee was persecuted and imprisoned for her beliefs, and among many Shakers, she was considered the second coming of Christ in female form.

From about 1837 to 1857, some Shakers began receiving images and messages — many believed to come from Holy Mother Wisdom, who the Shakers saw as the “personified feminine” aspect of God along with the “Almighty Father” as the masculine personification, art historian Sally Promey wrote in her book Spiritual Spectacles. Some people believed the messages came from departed loved ones, and they recorded them in paintings, dances, songs, drawings, and spirit writings, in which a scribe would capture characters and designs that looked like words and letters but whose meaning was unknown — kind of like a “visual equiva-lent for speaking in tongues,” Promey wrote. This period was known as the Era of Manifestations or “Mother’s Work.”

The “gift drawings” of that era burst with geometrical shapes, holy symbols, and heaps of color. The creators of the gift drawings called themselves “instruments,” not artists, and most were women and young people — typically “the least powerful members of Shaker society,” Promey wrote.

UPON READING THE news that the U.S. deported hundreds of migrants to El Salvador, I felt ill. Neri José Alvarado Borges had studied psychology and worked in a bakery. Luis Carlos José Marcano Silva is a barber with the face of Jesus tattooed on his stomach. As the daughter of an immigrant, I wept, thinking of their fear and families’ grief. In the face of a government that thrives on cruelty, we need resources that help us preserve our human capacities for hope, courage, and compassion.

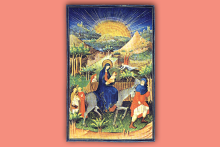

Recently, I’ve found comfort in paintings from books of hours, a form of prayer book popularized in Europe in the 1200s to make contemplation simpler for the laity. These paintings, known as “illuminations,” are distinctive and, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Wendy Alpern Stein, include “some of the greatest paintings and drawings of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance.”

Once the most published texts of their time, books of hours were often bespoke, commissioned by monarchs and aristocrats and crafted by luminary artists of the day. Each unique book of hours contains a liturgical calendar, gospel excerpts and psalms, and “The Hours of the Virgin,” which Stein calls “the heart” of the form, “a series of prayers and praise for the Virgin Mary [recited] at the eight canonical hours.” The books were made and written by hand. The illuminations include beautiful borders, often of botanical elements like ivy or flowers that decorate the edges of each page. Passages of text begin with an ornately decorated and framed capital letter. And the illustrations that complement the prayers and readings are drawn with vibrant colors and metals like gold and silver.

WHEN ANTONI GAUDÍ became the chief architect for Barcelona’s Sagrada Família Basilica in fall 1883, he had no illusions that he would live to see its completion. “There is no reason to regret that I cannot finish the church,” he said. “I will grow old, but others will come after me. What must always be conserved is the spirit of the work, but its life has to depend on the generations it is handed down to.”

After 142 years of construction, Gaudí’s masterpiece is slated to be finally completed in 2026, 100 years after Gaudí’s death. The finished basilica will have three distinct facades, only one of which was completed in Gaudí’s lifetime, and 18 towers — 12 for the apostles, four for the evangelists, one for the Virgin Mary, and the tallest and most central tower for Jesus. When you look at the Barcelona skyline from Park Güell, where the architect lived for almost 20 years, the basilica soars above the rest of the city, clothed in scaffolding. From far away, the cone-shaped, sand-colored spires look like intricate, naturally occurring stalagmites, reaching toward the heavens.

Gaudí’s iconic style — lots of curves, a heavy use of mosaic, and motifs from nature and Catalonia — was an extension of the broader artistic movement of Modernisme, the Catalonian cousin of Art Nouveau. Even though some of the visual language of the Sagrada Família had precedent in buildings such as the Castell dels Tres Dragons or the Palau de la Música Catalana, both by Lluís Domènech i Montaner, the basilica was still controversial. George Orwell once said that the Sagrada Família was “one of the most hideous buildings in the world,” and lamented that it hadn’t been destroyed during the Spanish Civil War. But more than a century later, Gaudí is widely recognized as an artistic genius, and his works have UNESCO World Heritage site status.

There are no exact right angles in the Sagrada Família’s design because Gaudí believed right angles didn’t occur in nature. Instead, you will find the spiral of a shell, the honeycomb structure of a beehive, the branches of a tree, and the unique curvature of a leaf. He also pioneered the mosaic technique known as trencadís, where pieces of ceramic or glass were broken into irregular shapes and applied to the surface of a form.

THE DAY AFTER the presidential inauguration in January, Episcopal Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde, preaching at a prayer service for unity attended by President Donald J. Trump, warned members of the new administration that contempt is “a dangerous way to lead a country.” She pleaded for their mercy and compassion for the most vulnerable and outlined a vision for social healing founded on genuine “care for one another.” Budde’s words stand in stark contrast to the campaign of dehumanization and destruction we’ve witnessed since.

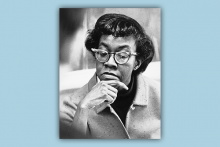

In the last few months, I’ve contemplated how, with incredible grace, Budde spoke truth to the power sitting before her in the pews. Her sermon left me feeling calm and convicted and brought to mind one of my favorite artists, the 19th-century impressionist Mary Cassatt. Like Budde’s sermon, Cassatt’s paintings are striking in their softness; they remind me of the kind of activist and person I want to be. I want to live with my heart softened and meet suffering with tenderness.

As Ruth E. Iskin explains in Mary Cassatt Between Paris and New York, Cassatt was “neither simply or completely a bourgeois, nor fully a precursor to the 1890s New Woman, but a mixture of both.” She was “anchored in a transatlantic network that included numerous conservative Americans” and an independent working woman who passionately supported women’s suffrage and full emancipation. In a male-dominated art scene, Cassatt made a name for herself with humanizing portraits of women of all ages, showing the relationship between caregivers and children and the dignity of motherhood. Her layered, emotionally vulnerable pieces highlighted the strength of women and the beauty and seriousness of care itself.

Her politics were characterized by a similar sensitivity. Iskin explains, “[Suffragists] claimed that the very role of mothers in the private sphere justified extending their activity into the public sphere of politics and government.” In other words, they made the case that the qualities of love, strength, and commitment exhibited by many women in their homes would also benefit civic spaces.

I FIRST CAME across digital media artist Madeleine Jubilee Saito’s work on social media. While scrolling through a sea of Instagram stories about environmental disasters, civil unrest, and humanitarian strife, I reached a square that made me pause: a multicolor four-panel image from a digital watercolor comic. I took in the top two panels of a gray figure staring out into the sky and then the glimmering, fruited foliage framing the bottom two panels. It felt like a vision from a better, more just future. The text on each panel, though brief, was powerful. I took in each word like a sacred telegram: THE GREAT WOUND / IS HEALED / ALL THINGS / MADE NEW.”

When I was younger, I found comfort in dynamic plotlines nestled in the predictable geometry of print and online comic series. Through Saito’s work, that comfort returned to me, in the form of four panels grappling with climate grief and environmental repair.

When I spoke with Saito about her work, she said that her affinity for comics started in high school. “As a young person, I had a very hard time accessing my own feelings or seeing that my interiority or my life were particularly valuable,” she said. “Comics were a way I could crystallize that value and the meaning of my own interiority for others — make it visible.” Now, Saito’s work conveys the value of the natural world. In her ecological storytelling, we see portraits of people amid towering trees and shimmering waterways. Her human subjects submerge themselves in the elements; her natural subjects invite readers to take a closer look at this numinous world.

Her upbringing in northern Illinois exposed Saito to the tensions between humans and earth. She grew up in a house deep in the woods — “a strip of forest in the middle of this desolate monocrop landscape,” she said, explaining how she saw beauty amid exploitation. “The animals — raccoons and possums — were pests to be managed. Every year the trees and bushes and plants from the forest would encroach further toward the house and every year they would need to be cut back.”

This awareness of the adversarial relationship with the natural world has guided her work and now culminates in her debut book, You Are a Sacred Place: Visual Poems for Living in Climate Crisis (Andrews McMeel, 2025). The first section explores the doom happening parallel to climate collapse. In one story, we see someone curled up in bed, sinking into and verbalizing their sadness post-job layoff. Wildfire smoke chokes the Seattle air around them. In this panel, I see myself, two years ago, numb from financial despair while wildfire smoke cast a noxious orange hue over Philadelphia.

DURING MOST RECENT winters, my sister has heard me declare, excitedly, “Baseball is almost back!”

This may be surprising. Perhaps that’s because I am a Black man in my early 30s. (There aren’t that many of us longing for baseball anymore.) But it also may be surprising because my favorite team is the New York Mets. And if you know anything about the Mets, you know that to be a Mets fan is to be a friend to frustration, not to excitement.

I guess I was saved from some frustration because school and the lack of the necessary cable TV bundles made it hard for me to follow the team as closely as I would’ve liked during the 2010s and much of the early 2020s. Most of those years ended with the team losing more games than they won. And yet last year, with the blessing of a full-time job, I was glad to purchase a streaming service that allowed me to regularly watch my favorite team again.

Being a baseball fan — if you let it — can train your spiritual muscles in a way that few other activities can. Do you care about daily rituals like prayer? Baseball, unlike most professional sports, is typically played six or seven days a week. Are you working toward a cause, like human rights, that is mostly out of your control? Baseball reminds us that no one player, no matter how good they are, can single-handedly make their team win a championship (shoutout to Mike Trout).

I LOVE TO walk. I came by this love naturally. My mother, now well into her 80s, is a dedicated walker, spending at least 30 minutes each evening walking on her treadmill. In earlier years, especially when the winds of the Kansas plains died down late in the day, she would walk the half-mile dirt road to our mailbox and back.

I’ve added three Labrador retrievers to my walking ritual — Hershey, Pippi, and Rue — who delight in a daily routine of getting outside, noses to the ground, tails in the air, ears perked and attuned. Responding to the rattle of their leash, each one’s anticipation is uniquely their own — a hop, a tail whipping against my leg, a wet nose urgently working to get the collar in place.

In recent years, after experiencing the awe of walking in the Pacific Northwest, where lush forests and rippling rivers drew my husband and me to their sacred cathedrals, we have started structuring vacations around where we want to hike. Step after step, we take in nature’s altars, praying with our feet, ingesting nature’s elements in holy, full-bodied communion.

In her book Enchantment: Awakening Wonder in an Anxious Age, Katherine May articulates what I feel when I’m walking. Enchantment, she writes, evokes a deep knowing that “something is there, something vast and wise and beautiful that pervades all of life. Something that is present, attentive, behind the everyday. A frequency of consciousness at the low end of the dial, amid the static. A stratum of experience waiting to be uncovered.” This is precisely why I have taken my worship on the road.

The Bible is replete with people who go walking and end up finding themselves in the process. Patriarch Abram, for example, was called to leave his home in Ur and walk to a new place in a more fertile valley where he made his new home with Sarai. Or consider the ancient Israelites who escaped the oppressive Egyptian pharaoh — and walked in the desert for a generation. Also don’t forget one of the Bible’s most familiar walks: the one taken by Ruth and her mother-in-law, Naomi. While the narrator shares few details of their journey, their trek from the hinterlands back to Naomi’s hometown must have been an adventure of dangerous proportions.

Walking requires a willingness to leave one place and go to another. And somewhere along the road, in the liminality of “not-there-yet,” transformation becomes possible.

IN “KITCHENETTE BUILDING,” Gwendolyn Brooks, the first Black Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, considers the challenge of dreaming in grim places. The setting of this 1945 poem, published as part of Brooks’ first collection, A Street in Bronzeville, is the titular kitchenette building, a housing unit of many cramped, run-down apartments, often rented by Black residents in that era in cities like Chicago. Tenants are “grayed in, and gray,” worn out by systemic injustice and the demands of daily life, such as paying rent and putting food on the table. Still, the speaker — who speaks on the behalf of a collective “we” — wonders if a dream could rise “through onion fumes” and “sing an aria” in the building.

The dream in “kitchenette building” is delicate and “fluttering,” something that requires time and contemplation — luxuries that systemic oppression makes nearly impossible. Brooks’ biographer, Angela Jackson, in A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun: The Life & Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks, describes this poignantly: “Life is grim in these kitchenette buildings ... entrapment as in a prison. People here are not people; they are things, dehumanized by the nature of a system they did not volunteer for.” Later, she asserts that kitchenette residents “cannot even consider” a dream greater than a cold bath “[before] a realistic necessity comes up ... They take what they can get.”

Brooks makes it clear, though: Imagination is a vital precursor to liberation. “Kitchenette building” plants seeds in questions: What would happen if dreams of freedom and freshness had space to grow? What would liberation look like for Black communities and the U.S. as a whole?

THE DAY AFTER I told my mother I was transitioning, I sat across from a childhood friend, who I’ll call Sarah, in Los Reyes, my favorite Mexican restaurant in my hometown. It was 2009, and I had come home from college specifically to give my mom the news. I hadn’t seen Sarah in six years but I remembered she had a strong faith that she shared openly and invitationally. As soon as I sat down, she asked how I was doing. Something in me broke open, yearning to be seen. I was a mess — sadness and anger dipping in and out of despair. I said something like, “My mom’s just never understood me, and now she’s not going to try to understand.” Sarah got quiet and nodded before replying, “So? I don’t understand either, but I’m here because I love you.”

Whatever I said in response doesn’t matter as much as the truth I learned: Friends and family can love and support one another without understanding them.

In last year’s documentary Will & Harper, Harper Steele, a trans comedy writer living in New York, has one such friend in the comedian Will Ferrell. At the beginning of the documentary, we learn that Steele announced the news of her transition via an email to her loved ones, Ferrell included. Upon hearing the news, Ferrell, who’s been friends with Steele since the two met on Saturday Night Live 30 years ago, is shocked but wants to be supportive — he’s just not sure how.

“So many of us don’t know what the rules of engagement are,” Ferrell says. “And in terms of our friendship and our relationship, it’s uncharted waters.” So he invites Steele to go on a road trip with him.

Ferrell describes Steele as a rough-and-tough, beer-drinking Midwesterner who loves finding seedy roadside bars and truck stops on cross-country drives. But both he and Steele are worried those dive bars will not be safe now that Steele is living as a woman. So the motivation for the trip is twofold: They can learn how to navigate the new circumstances of their friendship, and Steele can learn to navigate the places she’s always loved — this time as the person she’s always known herself to be.

AMERICAN EVANGELICALS LIKE to assume that reading the Bible is easy, that a plain reading exists. If only people were to hold our favorite English translation in their hands, Godself would arrest the reader, Truth making itself obvious on the tissue-paper pages. And voila! We would discover a clear path to world peace (or at least denominational peace).

Unfortunately, Bible reading is not so simple. Sometimes, we as readers have gotten the meaning of the text wrong. Sometimes commentators have allowed bias to shape interpretation. And sometimes, the problems start nearer to the root, in the translation itself. For example, the question of women’s roles in the Bible represents a tower of errors built up over time.

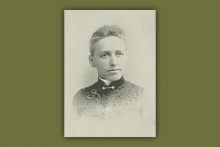

Katharine Bushnell, an American medical missionary to China who was fluent in the biblical languages, was one of the first female translators to take on these errors directly. In her 1921 commentary, God’s Word to Women, she painstakingly retranslated and corrected 100 Bible passages that referred to women and women’s prescribed roles within the home and church.

And she starts at the very beginning. While many male translators had written that in Genesis 2:21 Eve was formed by God from Adam’s “rib,” those translators render that same Hebrew word as “side” the other 42 times it recurs in the Old Testament. Bushnell explains that the Hebrew language contains a different word that explicitly means “rib,” a word that the Genesis author does not utilize in the account of Eve’s creation. Yet even today, a corrected translation appears only as a footnote in my NIV Bible. So, why has the mistranslation of Eve as created from the “rib” of Adam — rather than his “side” — persisted?

THE BIBLE REPEATEDLY points us toward understanding God as a parent. Jesus recommends we call God “Dad,” or “Abba” in Aramaic (Matthew 6:9), and compares himself to a mother “hen [who] gathers her chicks under her wings” (Luke 13:34). And in the Hebrew scriptures, God often appears as a parent. Consider this description of God’s relationship to us from Hosea 11:3-4 and see if you don’t get a little misty-eyed: “Yet it was I who taught Ephraim to walk; I took them up in my arms, but they did not know that I healed them. I led them with cords of human kindness, with bands of love. I was to them like those who lift infants to their cheeks. I bent down to them and fed them.”

As a parent, I get glimpses of that love: The joy I felt watching my daughter score her first goal in soccer. The worry I felt when I saw her fight through a string of stomach bugs. But most surprisingly, I’ve caught glimpses of God’s parental love when watching kids’ movies with my child, particularly films from 2024.

One moment in particular, a scene from Despicable Me 4, of all things, really hammered home the link between parenting and God. Throughout the film, the main character, Gru, struggles to connect with his son, Gru Jr. When Gru Jr. finds another father figure, someone who will bring harm to Gru, Gru still offers his child one last gift by saying, “It’s okay, Junior. Dada loves you.” There was something about that scene showcasing the fierce love of a parent for their children, even when that love hurts, that made me understand that movies, especially kids’ movies, can be a fantastic way to gain some understanding of what God’s love might look like.

A NETWORK OF outspoken Christian nationalists is growing in popularity. They are not yet mainstream, but their drive for power is irrefutable. In Onward Christian Soldiers, the second season of the NPR podcast Extremely American, hosts Heath Druzin and James Dawson trace the rise of this Christian nationalist movement as manifested in the ministry of Doug Wilson, the reactionary, fundamentalist pastor of Christ Church in Moscow, Idaho.

Wilson and his followers are forthright about their goal. “Our mission at Christ Church is summed up by the phrase, ‘all of Christ for all of life,’” according to the mission page on the church’s website. “Under the grace of God, this means that our desire is to make Moscow a Christian town.”

Across eight episodes, listeners of Extremely American witness Wilson’s emergence: The son of a Christian bookstore owner, Wilson takes on the mantle of preacher, excels in his philosophy classes, becomes an intuitive builder of institutions, and uses these skills to advance a crude political vision of Christian domination.

DORCAS CHENG-TOZUN, author of Social Justice for the Sensitive Soul (Broadleaf), wanted to be an “unceasing voice” for social justice. “And while I was busy saving the world,” she writes, “I would also be the kind of person who’d happily sacrifice anything for a good cause.” But 10 months after Cheng-Tozun moved from the U.S. to China to set up an operations office for her spouse’s solar business, thrilled at the possibility of providing affordable electricity to billions of people, she experienced the “worst and longest panic attack” of her life. For more than a year, she could do “little more than sleep and cry and journal.” A crucial, difficult question arose: “Why can’t I handle what everyone else seems to be managing perfectly well?”

For Trish O’Kane, author of Birding to Change the World (Ecco), the breaking point was Hurricane Katrina, which destroyed her New Orleans home and neighborhood. “After a disaster,” O’Kane reflects, “you just can’t do as much. Nor should you. You need time to think, to ponder ... I needed a great slowing down.” She took up knitting, spent long hours outdoors on the ground “watching the clouds change shape and bumblebees loading their back legs with pollen and the yard birds going about their business.

Like Cheng-Tozun’s year of sleeping, crying, and journaling, these months surfaced life-changing questions for O’Kane. “I could feel my question changing,” O’Kane writes, “from What should I do? to How should I be?”

In their respective books, Cheng-Tozun and O’Kane write from the other side of activist burnout — something Cheng-Tozun experienced after working for multiple social justice organizations, and O’Kane after working in human rights journalism in conflict areas, both for many years. Both writers ponder how to change, heal, and move forward. Birdwatching was the gateway for O’Kane, while Cheng-Tozun found herself reflecting on sensitivity, introversion, and the many ways people are wired with different gifts to offer. They have different backgrounds and stories — Cheng-Tozun is now a writer and consultant who most recently worked for a Christian nonprofit that equips BIPOC contemplative activists; O’Kane is an environmental educator who created the “Birding to Change the World” program at University of Wisconsin-Madison — but both authors offer a similar invitation to those who yearn to make a difference: Learn to embody gentler, more sustainable ways of doing so.

WE STOOD AT the base of a sticky, bright mountain, a 50-foot-high altar of hay and clay and thousands of gallons of paint proclaiming “GOD IS LOVE” in chunky letters. We shaded our faces from the hazy-sizzling sky to see the white cross at the very top, blue stripes streaming down the sides, a parade of happy flowers at the base. “Say Jesus I’m a sinner please come upon my body and into my heart” is written into a giant cherry-red heart.

My friends and I were 19 years old and seeing Salvation Mountain, the folk-art stronghold, for the first time. We learned about Salvation Mountain the way most people do these days: through friends on Instagram. We drove three hours east from San Diego to Niland, a tiny census designated place in Southern California’s Imperial Valley, a desert landscape of sagebrush, sand, and brassy wind. Salvation Mountain’s artist, Leonard Knight, began building the mountain in 1984 and maintained it every day until his health began to fail in 2011. He died in 2014.

The prayer in the big red heart was what Knight prayed on the day he experienced a born-again moment and heard God call him to build a mountain proclaiming universal love to the world. When we visited, he’d been dead for a few years, and the mountain was getting cracked and worn, the paint tearing up in chunks. Knight built other structures next to the mountain, including a shaded “forest” of what he called “car tire trees”: stacks of tires for trunks and crisscrossed poles for branches, mixed with adobe and straw and painted bright colors. We quietly moved among them. “God is love” appeared again and again on the crevices and lumps, like a psalm. I felt it in my chest, that ache it takes to devote all of one’s creativity and being to God.

COMPLETELY BY COINCIDENCE, travel writer and translator Shahnaz Habib once joined thousands of pilgrims in Lalibela, Ethiopia. Habib’s trip happened to overlap with Ethiopian Christmas, which brings Ethiopian Orthodox Christians from across the country and world to the town, famous for its medieval rock-hewn churches.

Detailing her experience in her book Airplane Mode, a personal history of travel with a sharp eye for the colonial legacies in tourism, Habib calls Lalibela’s churches “marvels of subterranean engineering.” Carved from red volcanic rock, they sit embedded in the ground, connected by tunnels. The complex of structures was built in the 12th century as an homage to Jerusalem, complete with replicas of Christ’s Nativity crib and tomb.

Habib observed as her fellow travelers lined up around the churches to kiss crosses offered by priests: “A kiss at the top of the cross, a kiss at the bottom, a touch of the cross to the forehead. Hundreds of kisses every hour.” She noted the procedural quality of the ritual.

“To lose oneself in a crowd. To walk the beaten path. To wait and be bored,” she writes. “Perhaps what separates the tourist and the pilgrim is not the reasons for their travel but the satisfaction that the pilgrim finds in what frustrates the tourist.”