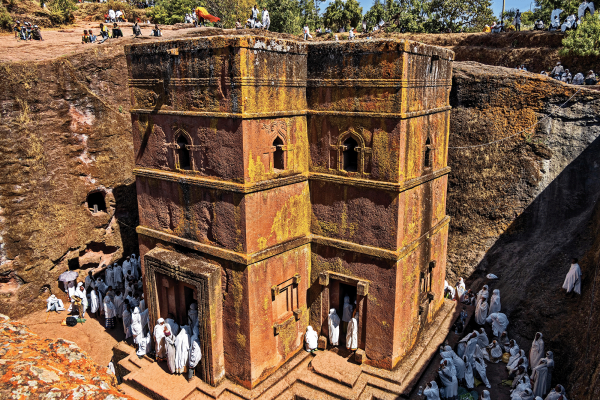

COMPLETELY BY COINCIDENCE, travel writer and translator Shahnaz Habib once joined thousands of pilgrims in Lalibela, Ethiopia. Habib’s trip happened to overlap with Ethiopian Christmas, which brings Ethiopian Orthodox Christians from across the country and world to the town, famous for its medieval rock-hewn churches.

Detailing her experience in her book Airplane Mode, a personal history of travel with a sharp eye for the colonial legacies in tourism, Habib calls Lalibela’s churches “marvels of subterranean engineering.” Carved from red volcanic rock, they sit embedded in the ground, connected by tunnels. The complex of structures was built in the 12th century as an homage to Jerusalem, complete with replicas of Christ’s Nativity crib and tomb.

Habib observed as her fellow travelers lined up around the churches to kiss crosses offered by priests: “A kiss at the top of the cross, a kiss at the bottom, a touch of the cross to the forehead. Hundreds of kisses every hour.” She noted the procedural quality of the ritual.

“To lose oneself in a crowd. To walk the beaten path. To wait and be bored,” she writes. “Perhaps what separates the tourist and the pilgrim is not the reasons for their travel but the satisfaction that the pilgrim finds in what frustrates the tourist.”

The distinction rings true, at least when the two kinds of travelers are thought of as archetypes. Pilgrims humbly search for divine presence, while tourists — especially those from wealthy countries — demand a truncated cultural immersion available in their language, paid for in their currency, flavored with the contents of their pantry. But as Habib lays bare in her book, rarely do travelers of any kind think or behave as stock characters, free of contradiction.

In fact, pilgrimage and tourism are linked. According to cultural and psychological anthropologist Naomi Leite, pilgrimage is one of the major threads that laid the groundwork for tourism as we know it today. These religious roots have helped imbue all sorts of travel with the possibility of self-improvement and even transformation. The tourism industry has smartly cashed in on this existential importance, taking the 19th-century invention of “wanderlust” and selling it as a kind of spirituality. Even the most commercial travel is sometimes couched in the language of virtue. Consider this advertising copy for a Sandals Caribbean Resort in Jamaica: “In this secluded spot, filled with the Earth’s abundance, love flows naturally.” The promise of spiritual renewal long associated with pilgrimage has become a feature of contemporary travel culture — without all the repentant waiting around, of course.

But billing travel as soul care is a thorny rhetorical move. Traveling today can mean participating in extractive economic relationships established violently by colonial powers or flying in commercial planes that collectively account for 3.5 percent of human-caused global warming. It can also mean contributing to the over-consumption of natural resources that harms quality of life in places such as Hawaii and Bali. Lodging creates issues too: Leite noted that short-term rentals now fill many major cities, driving up rent and emptying those areas of local life. Tourists always impact the spaces they enter, and they can thoughtlessly create “ripples of disturbance” in their wake — but what’s happened with Airbnbs in city centers is far more than a ripple of disturbance. “It’s like a bomb going off,” she told Sojourners.

Rituals, both the formally religious and loosely spiritual, become empty of their legitimacy if they don’t have implications for justice. What good is it to see the whole world but forfeit our souls?

Travel as a metaphor for faith shows up all over Christianity (most immediately evident in the name of this magazine). Much of this language emerges from stories of forced migration and persecution instead of voluntary travel, as is the case in Jesus’ own life: “the Chosen One has nowhere to lay his head” (Matthew 8:20). Paul’s Epistle to the Hebrews extends this sojourner identity to followers of Jesus too, saying, “For here we have no lasting city, but we are looking for the city to come” (13:14). In The City of God, Augustine described the heavenly city as a “pilgrim society of all languages.” It’s no wonder that pilgrimages spread throughout the early Christian world toward places such as Lalibela or Santiago de Compostela in Spain. For many believers, the pursuit of holiness has been embodied in the pursuit of holy ground.

The thing is, I can’t think of any ground that isn’t holy. Whether we travel a block away or a continent over, to go anywhere on Earth is to arrive as a guest in a place touched by God. That is, to arrive as a pilgrim. To riff off Habib, what would it look like to travel as tourists while finding satisfaction in the things that should matter most to us as pilgrims, principally love of neighbor?

It’d be hard — if not impossible — to travel anywhere today, including for religious reasons, and not be complicit in the destructive elements of the travel industry writ large. The cleanest fix would be to largely abstain from air travel (something I haven’t had the courage to seriously consider). Robin L. Turner, professor of political science at Butler University, told Sojourners that in our “incredibly unjust world,” disengaging from tourism “isn’t a magical fix.” Turner has studied injustices within nature tourism. Many places around the world now deemed people-less natural paradises, including many U.S. national parks, were not too long ago — or still are — the homes of Indigenous people. One community Turner has worked with, the Makuleke people of South Africa, were forced off their land, which the government then incorporated into the country’s premier national park. Decades later, the Makuleke negotiated for their land and successfully reclaimed it — with conservation stipulations. Turner emphasized the importance of doing some prior research on places you’re considering visiting.

Ethical travel isn’t just about what to avoid; it can also be about what to include. Turner shared some ways travelers can “co-struggle” with the people who live in the places they visit, such as justice-focused walking tours. These include community-led “toxic tours,” which aim to raise consciousness surrounding local environmental harms, and historical tours such as The Radical Black Women of Harlem Walking Tour, which teaches participants about those who have struggled for justice in Harlem and beyond.

The travel industry needs quite the transformation. So do its travelers. If we want to see the world — for what it is and what it could be — we’ll have to move through it differently.

Given the ways that faith and travel have circled each other over the millennia, I wasn’t surprised when, in Airplane Mode, Habib borrowed the frame of religion to describe her relationship to tourism. “This religion of tourism, its holy books and its rituals, is deep within me, even when I strike out on supposedly non-touristy paths,” she writes.

Perhaps it’s a good thing that the line between tourists and pilgrims is a fine one: All kinds of journeys can feel sacred; it’s up to us to act accordingly.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!