Cover Story

Ivonne Wierink / Shutterstock

In April 2016, Roman Catholics from around the world gathered at the Vatican to discuss how the church might embrace the principles of nonviolence and just peace more deeply (see "Game Changer?" in the December 2016 issue of Sojourners.)

And what does "just peace" include? Here are seven key principles:

Just cause: protecting, defending, and restoring the fundamental dignity of all human life and the common good

Right intention: aiming to create a positive peace

Participatory process: respecting human dignity by including societal stakeholders—state and nonstate actors as well as previous parties to the conflict

Right relationship: creating or restoring just social relationships both vertically and horizontally; strategic systemic change requires that horizontal and vertical relationships move in tandem on an equal basis

Reconciliation: a concept of justice that envisions a holistic healing of the wounds of war

Restoration: repair of the material, psychological, and spiritual human infrastructure

Sustainability: developing structures that can help peace endure over time

Adapted from “What Kind of Peace Do We Seek?” by Maryann Cusimano Love, associate professor of international relations at the Catholic University of America, in Peacebuilding (Orbis Books, 2010).

RELIGIOUS LIBERTY is very popular in the abstract. It’s only in its application that we begin shouting at one another.

Take the executive order on religious freedom that President Trump signed earlier this year: Depending on your perspective, the order was either “a welcome change in direction toward people of faith from the White House,” as Southern Baptist Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission president Russell Moore said, or it was a smokescreen for bigotry giving the U.S. government “license to discriminate,” in the words of Sarah Warbelow of the Human Rights Campaign.

So how did we get here?

Lee Nanjoo / Shutterstock.com

1. Continue developing Catholic social teaching on nonviolence. In particular, we call on Pope Francis to share with the world an encyclical on nonviolence and just peace.

2. Integrate gospel nonviolence explicitly into the life, including the sacramental life, and work of the church through dioceses, parishes, agencies, schools, universities, seminaries, religious orders, voluntary associations, and others.

3. Promote nonviolent practices and strategies (e.g., nonviolent resistance, restorative justice, trauma healing, unarmed civilian protection, conflict transformation, and peacebuilding strategies).

4. Initiate a global conversation on nonviolence within the church, with people of other faiths, and with the larger world to respond to the monumental crises of our time with the vision and strategies of nonviolence and just peace.

5. No longer use or teach “just war theory”; continue advocating for the abolition of war and nuclear weapons.

6. Lift up the prophetic voice of the church to challenge unjust world powers and to support and defend those nonviolent activists whose work for peace and justice puts their lives at risk.

The Catholic Nonviolence Initiative is a consortium of attendees from the Rome conference and others who are advocating for a papal encyclical on nonviolence. Read the full statement at nonviolencejustpeace.net.

IN JUNE, THE U.S. SUPREME COURT ruled in favor of a Lutheran church in Missouri seeking state funding to replace the gravel yard of its playground with a softer surface made of recycled tires. But was it a victory for religious freedom or a violation of the principles separating church and state? Sojourners associate editor Betsy Shirley interviewed Charles C. Haynes, founding director of the Religious Freedom Center of the Newseum Institute, to help sort it all out.

Sojourners: Let’s start with the basics: Where does the idea of “separation of church and state” come from?

Charles Haynes: The Establishment Clause—or, more accurately, the “no establishment clause”—is the part of the First Amendment that separates church from state, preventing the entanglement of religion and government that has been the source of repression and conflict for much of human history. But it also protects the right of religious groups and individuals to participate fully in the public square of America.

Awe Inspiring Images / Shutterstock.com

'WE CAN JOYFULLY anticipate an abundance of cultural differences and varied life experiences among the participants in the Rome Conference,” wrote Pope Francis in his welcome letter to the Nonviolence and Just Peace gathering in Rome, “and these will only enhance the exchanges and contribute to the renewal of the active witness of nonviolence as a ‘weapon’ to achieve peace.”

Nowhere were the “cultural differences” and “varied life experiences” more conspicuous than in the conversation about whether there is ever a Christian justification for armed force.

U.S. and Western European academics are thoroughly trained in the theory, theology, and application of just war theory. It’s taught in U.S. and European seminaries. It’s taught in all military academies. It provides a framework for international law.

In stark contrast, Catholics living in Iraq, Sudan, Uganda, Afghanistan, Syria, Congo, Sri Lanka, and other war-torn countries are not schooled in just war philosophy. It is not part of training for priests or academics or those in political life. When people from war-ravaged regions talk about “just war,” they speak from the experience of having been on the receiving end of “morally acceptable” drone strikes. They make a powerful argument for a paradigm shift away from just war thinking.

In regions of civil unrest, some said, where religious extremism is used as propaganda to advance partisan military and political objectives, even associating the language of “just war” with Catholicism can categorize Catholics as “combatants.”

In the case of Colombia’s brutal, 52-year-long civil war, Jesuit priest Francisco De Roux described how just war teaching misled Catholics into taking up arms. “In my Catholic country,” said De Roux, “our nuns and priests join the guerillas because of the just war paradigm. The Catholic paramilitaries pray to the Virgin before slaughtering people because of the just war paradigm.”

THE UNEXPECTED ELECTION of Donald Trump plummeted me into such a mood of disbelief, emotional reactivity, and political angst that I was losing my spiritual center. Responding on Facebook to the latest outrage, while perhaps politically therapeutic, wasn’t satisfying my soul. I needed to become grounded again with my deepest self and with God.

At a lunch with friends from church to process the aftermath of the election, my wife, Karin, said, “Donald Trump is going to say or do something every day that will arouse us emotionally. And we can’t allow ourselves to be stuck in that place of continuous arousal, responding to him. We have to find safe spaces to support proactively the things we’re called to do.”

More than any in recent memory, this election has sent a spiritual disturbance rippling through society and people’s lives. For many followers of Jesus, and especially those who are not white evangelicals, Donald Trump’s presidency has come to feel like more than a disagreeable political program; rather, it directly contradicts and threatens the integrity of their Christian faith and undermines its public witness. The values underlying the Trump administration, co-mingled with a personality that is narcissistic, pugilistic, and vindictive, has become an assault on what Christian ethics teaches and what we hope our lives stand for.

The inner lives of many have been thrown into spiritual disequilibrium. Even while we search for political responses and may find encouragement in the unprecedented mobilization of the millions marching on every continent, we need to discover the roots for resistance and creative public engagement that can be spiritually sustained for the long run.

I’ll put it this way: When they go low, we go deep.

Jmaggiophoto / Shutterstock.com

"In the wake of this election, the role of faith communities is imperative," writes Jim Wallis in "Resistance and Healing." With this in mind, we asked a few Christian leaders how followers of Jesus can best practice resistance and healing in Trump's America. Though varied, the responses we received have a common theme: Christians must stand in solidarity with the vulnerable. Now and always. —The Editors

Resistance is Holy Work

by Brittany Packnett

RESISTANCE IS HOLY WORK. Resistance is what it means to tell the truth and defend people in public, even—and especially—when it is inconvenient, dangerous, and uncomfortable.

What truths must we tell? We must tell the truth that the entire world is not white, straight, Christian, cis-gendered, American-born, male, or able-bodied, and that those of us who aren’t matter just as much as those of us who are. We must tell the truth that rhetoric and policies that encourage violence against those same people is not of God and not of the freedom we espouse. We must tell the truth that if all of us were truly created equal, then the cancer of xenophobia makes all of us sick—and that none of us are truly free until we are all free.

We did not lose an election as much as we validated and normalized a way of life that is beneath our humanity—and, therefore, which requires our resistance. The Christ I serve did not sit idly by in times like these—for in eras like this one, inaction is a sin. Inaction perpetuates this latest wave of hate just as much as if you painted a swastika yourself. Hate should never be welcome in our homes, at our tables, in our worship, or in our country.

It is holy to resist such things. Holy resistance means calling out that hate by name and casting it out of where you are—of where you want God to be. Casting it out means no longer making excuses that your grandfather just talks like that because he is elderly; it means withholding your tithes and membership from those places that will not be safe havens and sanctuaries for those persecuted under potential new rules of law; it means challenging the notion that we stitch together a false unity rather than acknowledge the explicit danger many of us are now placed in.

Holy resistance means praying for those who persecute—but protecting the persecuted. Christians must be people of moral conscience, those who conscientiously object to hatred, division, racism, and sexism as unashamedly as we claim Christ. The call to be in the world and not of it was for such a time as this—we must be the light that shines on injustice and calls out our humanity to replace the evil we see.

Resistance is holy work. That makes it our work.

Détail de Pilate et des accusateurs/ Pethrus / CC BY-SA 3.0

LONG AGO AND FAR AWAY, a prisoner under arrest for treason faced his judge. The judge asked him about his beliefs and his political aspirations. “You can accuse me of wanting to be a ruler,” the prisoner replied, “but all I can say is that I came into this world to testify to the truth.” The judge was deeply scornful. “What is truth?” he said, and turned on his heel and walked away.

If you were working for a great empire, as was this judge and governor, you would be far more concerned about power than about truth. In fact, later in the trial, the judge reminded his prisoner that he had the power to release or execute him. The judge cared more about enhancing his own power and reputation in the empire than about meting out justice. The life of a powerless prisoner, along with the concept of truth, was expendable.

Today, truth itself may be expendable in the United States. A few years ago, comedian Stephen Colbert coined the word “truthiness” to describe that reality. But in the power struggle of our recent presidential election and the resulting shift in leadership, truth is becoming more and more squishy. Thus the Oxford English Dictionary added a stronger word in 2016: “post-truth,” defined as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” As Oxford’s usage example puts it, “in this era of post-truth politics, it’s easy to cherry-pick data and come to whatever conclusion you desire.” No doubt the fake news we have seen and heard on social media is sure to continue.

WHERE MUST we start as Christians and faithful churches after such a devastating election that brings the most dangerous man to the White House that we have seen in our lifetimes?

First, many people are terribly afraid, because they are from groups who were attacked and targeted in the campaign by the new president-elect. We must take those attacks seriously by reaching out in solidarity and protection to those who are now most vulnerable—undocumented immigrants, black and brown Americans, Muslims, women of all races, and LGBTQ folks. Members of these groups have already experienced ugly incidents of hate and violence, including increased harassment, vandalism, and even assaults on children and others in the wake of the election results. If I read my scriptures right, those are the people that Christians and other people of good conscience should now turn to in solidarity and support. That is what Christians are supposed to do: Support the poor, the vulnerable, and those under attack.

Second, we must make it very clear that honest and prophetic truth-telling about race in America will be needed as never before in our time, especially from white Christians. The fact that a majority of white Americans, at every level of class and gender, voted for a candidate who ran on racial and gender bigotry is even more distressing when we see that a majority of white Christians voted just like other white voters. And it is revealing that those who say this election was not about race are white, while Christians of color see race at the center of it. Repentance by white Christians in America will require the replacement of the white identity politics that dominated this election with faith identity politics.

One of the saddest aspects of the election for me is the fact that most white evangelicals voted for a man whose life has embodied the most sinful and shameful worship of money, sex, and power and who represents the very worst of what American culture has become.

THE STANDING ROCK Sioux Nation has actively opposed the construction of an oil pipeline intended to cross the Missouri River adjacent to their land since learning of the planned route in 2014. Joined first by Native American tribes from across the country, and more recently by others including military veterans and clergy, the “water protectors” scored a major victory in December when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers denied permits for the construction of the river crossing and, as we went to press, began examining the environmental impact of alternative routes. —The Editors

A thin layer of smoke from dozens of campfires hung low in the air over the Oceti Sakowin camp the morning of Nov. 3. More than 500 faith leaders had assembled at the camp’s sacred fire in solidarity with water protectors who have held vigil on the shores of North Dakota’s Cannonball River since April.

Rev. John Floberg, supervising priest of the Episcopal churches on the North Dakota side of Standing Rock, led the gathered clergy encircling the camp’s perpetual sacred fire in a ceremony of apology and repudiation of the Doctrine of Discovery, the papal edict issued in 1493 granting Western colonizers the right of dominion over Indigenous peoples and lands.

Leaders from faith groups that officially have repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery—including Baptist, Episcopal, Lutheran, and Presbyterian—joined Floberg in the speakers’ area facing tribal elders, where they each read a portion of an adapted repudiation statement crafted by the World Council of Churches. Following the apology, copies of the Doctrine of Discovery were offered to the elders who were asked if they wanted to place the documents in the sacred fire. After conferring, one elder said, “This paper, these words, do not belong in a sacred fire.” They chose instead to burn the documents in vessels placed between faith leaders and tribal elders.

THIS TEXT SENT BY a relative at Standing Rock confirms the images we’ve been seeing from the Standing Rock demonstrations against the Dakota Access pipeline in North Dakota. On the evening of Nov. 20, local police with armored vehicles fired at water protectors and their allies with water cannons, tear gas, rubber bullets, and percussion grenades; hundreds were injured and several taken to the hospital.

Once again we are at the crux of legitimate protests, private corporate interest, and the use of police and military force to address the situation. Fall 2011 saw law enforcement dismantling Occupy Wall Street encampments throughout the nation, while various Black Lives Matter demonstrations from Ferguson to Baltimore have faced similar confrontation by law enforcement. In all these cases, law enforcement prioritized protection of private property.

This fall, the Morton County sheriff’s department in North Dakota put its muscle behind the companies building the Dakota Access pipeline. The relationship between the use of force for the establishment of order and corporate interests being represented by the government is a tangled and messy system that has been vividly on display at Standing Rock.

The ongoing militarization of the government’s responses to protests over the past five years raises the question of whether there is a legitimate role for law enforcement, including the National Guard, that does not violate the just war criterion of excessive and disproportionate force.

A number of law enforcement programs and districts are having success through the establishment of de-escalation training and principles in their ranks. By putting in place strategies that de-escalate the need for force, either from the protesters or law enforcement, space is opened for negotiations and resolution.

Military force should in no way, shape, or form be used for the protection of corporate interests, particularly over the well-being of persons. The primary goal of law enforcement in these situations ought to be de-escalation as peacekeeping for the sake of avoiding excessive and disproportionate force and for the protection of the dignity and integrity of all involved.

BrooklynScribe / Shutterstock, Inc.

“The walls are the publishers of the poor.” —Eduardo Galeano

But the student sat outside on a bench, pretending to text instead. Why? She admitted that she hesitated going in “for reasons I’m not very proud of”—there were four people on the street, all of them older than her and speaking Spanish, a language she didn’t understand. Three of them had tattoos and piercings. Was she encroaching on their neighborhood? Would that be considered offensive?

When you feel scared and intimidated, what do you do next? She busied herself in her phone until she thought they were gone, and then entered the store.

Later, she wrote:

So I went in, only to discover they were inside as well. I quietly went to look at candles, hoping no one would talk to me. However, the lady I wrote about to the class—the mother who had come to ask Doña Victoria for a prayer of protection for her son, the woman who helped me pick out a candle and patiently answer all of my questions—was the same woman I had avoided outside of the store. She was so willing to help a complete stranger who was so obviously not from the area that I felt incredibly guilty for judging based on her appearance.

Even though I am well aware this entire story sounds like something out of one of those “Chicken Soup for the Soul” books for preteens that teach lessons of cultural acceptance, volunteering for good, creating lasting friendships, etc., everything is completely true and the significance is only becoming apparent as I reflect back. I witnessed the blessing of candles for long-lasting love and safety from violence that day. I also walked away with a unique experience and new impression of Humboldt Park. No other neighborhood that I visited welcomed a complete stranger with such open arms.

Image via Alexandru Nika/Shutterstock.com

EARLIER THIS YEAR I heard Rev. William Barber of the Moral Mondays movement in North Carolina use the phrase “Mr. James Crow, Esq.”

Since hearing the phrase, I have been reflecting on the revised and updated name for Jim Crow, the comprehensive and brutal system of racial segregation, discrimination, and terrorist violence against black lives and bodies—explicit in the U.S. South, and often implicit in the North, throughout the 20th century.

I have been thinking about this new and more-sophisticated Mr. James Crow, wearing a white shirt and a tie instead of a white sheet and a hood and inhabiting the back rooms in state legislatures and corporate offices instead of rural backwoods lynching sites.

I’ve also been thinking about Mr. Crow’s strategy for the 2016 election and the years ahead.

Mr. James Crow’s biggest concern now is the transformational demographic shifts occurring in the United States, which by 2040 or so will see a significant milestone: For the first time, the U.S. will no longer be a white-majority nation and, instead, will be made up of a majority of minorities. That’s one of the most important facts in American political life today. This fundamental demographic shift in racial and cultural identity is underneath almost everything in U.S. politics—including the presidential election.

So with a suit instead of a sheet, how does Mr. James Crow, Esq., enact his strategy? And what are the servants of Mr. Crow saying to one another?

THIS NEW VERSION of Jim Crow has a clear, systematic strategy to protect white supremacy and promote racial segregation, discrimination, and even violence. He knows that even he, with all his power, can’t prevent the racial demographics of America from evolving. But he thinks he can obstruct and delay the changes that new racial demographics will bring to American life and politics. In apartheid South Africa, we saw that even when a racial group is in the minority, it can wield the power to oppress other races and protect its own supremacy.

Mr. James Crow’s five-part strategy includes:

THE FAMILIES SHOWED up early for the South Los Angeles planning commission meeting in late January. Parents stood in the back, soothing crying babies. A young girl leaned over a chair, coloring in a house with bright pink solar panels on a purple roof. “Clean energy can come from the sun,” her page read.

They showed up in force to oppose an oil company’s appeal to new and revised zoning restrictions on the Jefferson drill site, an oil field in their neighborhood. They lined up to share stories of the nauseating smells, disruptive noises, concerns about the risk of catastrophic explosion, and fears of the drill site’s long-term health impacts on their children.

When Niki Wong approached the microphone, she asked everyone against the oil field to stand. “Tonight families, children, and residents are here to stand for a healthy future,” she said, as nearly all the 70 attendees—except for the five representatives of the oil company—rose behind her.

Wong lives within a half mile of the drill site and walks by it every day. As the lead community organizer with Redeemer Community Partnership, a Christian community development corporation that has been working in South Los Angeles since 1992, she speaks not only for herself but also for her whole community.

Her faith community’s fight against the drill site represents a distinctive approach to ministry, one that introduces Christians to new social issues, including environmental justice. Embedding themselves into the community has allowed Wong and Church of the Redeemer, an Evangelical Covenant Church, to become powerful advocates for change.

At the appeals hearing, when the representatives of Sentinel Peak Resources, which bought the Jefferson drill site in 2017, described themselves as a “good neighbor,” Wong was incredulous. A native of Sugar Land, Texas, Wong is intimately familiar with the energy industry. Both of her parents and many friends work in jobs related to the industry.

When she tells friends about her work, she lays out the facts: The drill site operates in an area with a density of more than 30,000 people per square mile, with nothing but an 11-foot-high wall between the site and the multifamily residences next door. Church of the Redeemer meets in a school a couple of blocks away. Most residents are people of color and living in poverty. They are renters, nearly half holding less than a high school education, and about a quarter do not speak English.

“The desire and need for fossil fuels is creating sacrifice zones, and my neighborhood is one of them,” Wong tells them. “Part of what it means to be a Christian is thinking about these things and making decisions that would be in line with what is just and what takes care of people on the margins.”

Image via poorpeoplescampaign.org / CC-BY-ND-4.0

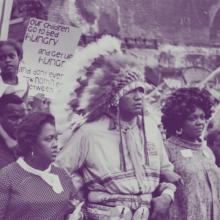

BY MOST MEASURES, the day had been a success. On the morning of Dec. 4, 2017, nearly 300 people crammed into a small room near Washington, D.C.’s Capitol Hill to reignite the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign. Camera crews filmed while clergy, Indigenous leaders, Fight for $15, Iraq Veterans Against the War, and state groups from around the country pledged their support.

From there the leaders marched to the U.S. Capitol to deliver a letter condemning the then-looming tax bill. “Woe to those who make unjust laws,” they read from Isaiah 10, “to deprive the poor of their rights.”

Later, the same crowd—plus locals lured by a lineup featuring Sweet Honey in the Rock, Maxwell, and Van Jones—gathered at D.C.’s Howard Theater to celebrate. Faith leaders and activists who’d linked arms together in places such as Flint, Mich., Charleston, S.C., and Standing Rock in the Dakotas sipped drinks and ate free ice cream provided by Ben and Jerry’s. The overall vibe was part social-justice pep rally, part family reunion.

But Rev. William Barber II wasn’t feeling it.

While the DJ played ’80s hip-hop, Barber lumbered onto the stage unannounced. He didn’t have a microphone, so he just started yelling. The perplexed stage crew scrambled to find a working mic, but Barber was impatient. The DJ cut the music and the theater grew quiet.

“My brothers and sisters,” boomed Barber once he had a mic. “This is a Poor People’s Campaign mass meeting and concert; this is not a party.”

‘Make this nation cry’

For the next 10 minutes, Barber worked his way through the litany of injustices that he and Rev. Liz Theoharis, co-chairs of the campaign, had repeated from countless pulpits over the past year as they crisscrossed the country recruiting people for the Poor People’s Campaign: deaths caused by lack of health insurance, the rollback of voting rights, corporate drilling on Native American lands, homelessness, police violence, an unlivable minimum wage, Flint’s inability to provide its citizens with clean water, political corruption. He spoke without notes, rambling at times (“I don’t have time to be scripted because the evil that’s happening is not scripted”), but it didn’t matter; as he neared the end of his list, the mood of the room had grown somber.

WHAT VALUES WERE really at stake for the 81 percent of white evangelicals who voted for a presidential candidate who uses crass language and admits to engaging in coarse behavior, and whose campaign was marked by vitriolic hatred of various people, particularly people of color?

I raised this question with a white male leader of a Christian foundation. In response, he told me to consider the “moral values”—such as pro-life concerns—that he said prompted, if not demanded, white evangelical support of Donald Trump’s candidacy.

The Christian leader suggested that these particular concerns mitigated any misgivings that white evangelicals might have with Trump’s dissolute behaviors and bigoted views. For many others, the moral imperatives not to support Trump were more overriding, especially for those who prioritize personal virtue as a core religious value.

The “value proposition” displayed by white evangelicals in the 2016 election, and the definition of what constitutes “moral values” and what doesn’t, is inextricably related to the nation’s upcoming demographic shift—the fact that, by the year 2044, the United States is expected to become majority nonwhite. This has significant implications for the wider faith community regarding issues of race. Much more may be at stake than the leader of the Christian foundation was able or willing to recognize.

‘The new Israelites’

The value proposition of the Trump campaign was made clear in the campaign’s “Make America Great Again” vision. This mantra tapped into America’s defining Anglo-Saxon myth and revitalized the culture of white supremacy constructed to protect it.

The Anglo-Saxon myth was introduced to this country when America’s Pilgrim and Puritan forebears fled England, intent on carrying forth an Anglo-Saxon legacy they believed was compromised in English church and society with the Norman Conquest in 1066. These early Americans believed themselves descendants of an ancient Anglo-Saxon people, “free from the taint of intermarriages,” who uniquely possessed high moral values and an “instinctive love for freedom.”

IN THE BOOK of Daniel, you find the words, “Can the God you serve deliver you?” Here’s the truth: The God we serve can deliver. But even if not, we will never bow down and serve other gods.

Daniel, set during the Babylonian exile, has something to say about history. It explores the vulnerability of people living under oppression. Many of the Israelites found themselves in bondage in Babylon.

There was a king of Babylon named Nebuchadnezzar. He was a mighty king, and when he issued an order, he meant business. Nebuchadnezzar was a narcissistic maniac who made everything about him. He made a golden tower, and he ordered that everybody under the reign of his kingship had to bow.

One day, Nebuchadnezzar called in those he had appointed and the ones he had pardoned, the governors and the sheriffs. He had a dedicatory service for his golden image, and he was trying to make sure that he wouldn’t have to lie about those who attended his inauguration.

Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, three young Hebrew men, represent the choices faced by those who must either support a repressive regime or face certain death. Nebuchadnezzar wanted them to bow—forget their heritage, forget their legacy, forget their journey, forget their God, forget their rights, and bow down. He wanted everyone around him to feel less than him, because he had his own inferiority complex.

The name Nebuchadnezzar literally means “one who will do anything to protect his power.” That’s why Nebuchadnezzar built his towers. He built his tower more than 10 stories tall. Nebuchadnezzar put his name on his tower. Everything he built, he put his name on it, because he was a narcissistic maniac. And then he put gold on his tower, and he promised that he, and only he, could make Babylon great again.

Are we in a “Bonhoeffer moment” today?

It is common to wonder what we would have done if we lived in history’s most challenging times. Christians often find moral guidance in the laboratory of history—which is to say that we learn from historical figures and communities who came through periods of ethical challenge better than others. Christians who wish to discern faithfulness to Christ often look back to learn how others were able to determine faithful discipleship when their contemporaries could not.

With this in mind, Dietrich Bonhoeffer may help us out today.

Bonhoeffer was a German theologian and pastor who resisted his government when he recognized, very early and very clearly, the dangers of Hitler’s regime. His first warning about the dangers of a leader who makes an idol of himself came in a radio address delivered in February 1933, just two days after Hitler took office.

Five Christian leaders on the influence of Walter Brueggemann’s classic book in their life and ministry.

KENYATTA GILBERT: What does “being prophetic” mean to you today?

WALTER BRUEGGEMANN: I think it means to identify with some clarity and boldness the kinds of political and economic practices that contradict the purposes of God. And if they contradict the purposes of God, they will come to no good end. If you think about economic injustice or ecological abuse of the environment, it is the path of disaster. In the Old Testament they traced the path of disaster, and it seems to me that our work now is to trace the path of disaster in which we are engaged.

The amazing thing about the prophets is that they were able to pivot, after they had done that, to talk with confidence that God is working out an alternative world of well-being, of justice, of peace, of security—in spite of the contradictions.

How do we establish a sense of clarity about who we think God is in this world of radical pluralism? As long as we try to talk in terms of labels or creeds or mantras, we will never get on the same page. But if we talk about human possibility and human hurt and human suffering, then it doesn’t matter whether we’re talking with Muslims or Christians or liberals or conservatives; the irreducible reality of human hurt is undeniable.