Gregg Brekke is an award-winning photojournalist and writer dedicated to telling stories of justice and faith.

Posts By This Author

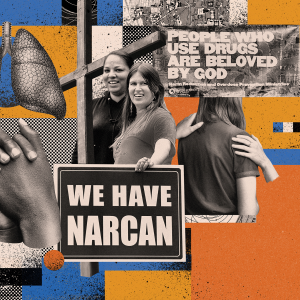

How Can Churches Serve People Who Use Drugs?

While sometimes controversial, faith-based harm reduction programs help save lives.

“WE ARE IN the midst of an overdose crisis,” said Hill Brown, southern director of Faith in Harm Reduction. “We say overdose crisis and not opioid crisis because right now overdose is the crisis. We’ve had opioids forever.”

In 2020 and 2021, during the height of deaths and extreme social isolation from COVID-19, deaths from overdoses surged in the United States before reaching a new baseline. The CDC estimates nearly 110,000 overdose deaths in the 12 months ending November 2023. That’s up from 71,350 deaths in the 12 months ending November 2019. Nearly 70 percent of these deaths were related to fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. For people 35 to 64 years old, the overdose death rate was highest among Black men and American Indian/Native Alaskan men at around 60 per 100,000 persons. Overdoses have become the third largest cause of death among teens 14 to 18 years of age, behind firearm deaths and vehicle collisions, rising to an average of 22 per week in 2022, largely driven by fentanyl in counterfeit prescription pills.

While churches have long hosted recovery groups focused on abstinence from drugs, some faith leaders are exploring how churches and other religious institutions can serve people who use drugs (PWUDs). By offering safer drug use resources such as sterile syringes and smoking supplies, fentanyl test strips, safe consumption sites, naloxone (an overdose reversal drug) training, and counseling, they are also working to extend this welcome and compassion without moralizing about drug use or judging PWUDs.

Collectively known as harm reduction, these practices were originally envisioned as strategies to curtail the spread of HIV. In this context, harm reduction aims to reduce the negative consequences associated with drug use. Its values include viewing PWUDs as sacred and beloved, believing love is greater than the law, allowing PWUDs to exercise choice, and centering a person-first approach that embodies compassion, dignity, and justice.

Jan. 6 Vigils Invoke Same God, Different Narratives

A year after the Jan. 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol, the District of Columbia remained largely silent. President Joe Biden gave a speech condemning the attack, Democratic members of Congress led remembrances, and different groups held vigils near the Capitol; a small group held a vigil in protest to the incarceration of those who participated in the Jan. 6 attack.

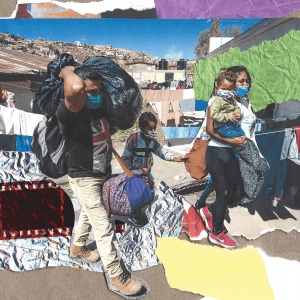

‘If They Felt Safe ... They Would Not Leave'

For many people in Honduras and elsewhere, leaving their home country is a matter of survival.

Corruption and climate disaster push many people in Honduras and elsewhere to make the uncertain journey north.

The Interfaith Chaplains of the Capitol Hill Organized Protest

Late Monday afternoon, dressed in clerical garb, eight chaplains – three Jewish, three Unitarian Universalist, and two Christian – went into the six-block area originally called CHAZ (the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone), along with their hand-drawn sign, a folding table, and a willingness to offer faithful presence for anyone who needed it.

A Chorus of Resistance

The resilient action at Standing Rock offers a model — and a sign of things to come.

THE STANDING ROCK Sioux Nation has actively opposed the construction of an oil pipeline intended to cross the Missouri River adjacent to their land since learning of the planned route in 2014. Joined first by Native American tribes from across the country, and more recently by others including military veterans and clergy, the “water protectors” scored a major victory in December when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers denied permits for the construction of the river crossing and, as we went to press, began examining the environmental impact of alternative routes. —The Editors

A thin layer of smoke from dozens of campfires hung low in the air over the Oceti Sakowin camp the morning of Nov. 3. More than 500 faith leaders had assembled at the camp’s sacred fire in solidarity with water protectors who have held vigil on the shores of North Dakota’s Cannonball River since April.

Rev. John Floberg, supervising priest of the Episcopal churches on the North Dakota side of Standing Rock, led the gathered clergy encircling the camp’s perpetual sacred fire in a ceremony of apology and repudiation of the Doctrine of Discovery, the papal edict issued in 1493 granting Western colonizers the right of dominion over Indigenous peoples and lands.

Leaders from faith groups that officially have repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery—including Baptist, Episcopal, Lutheran, and Presbyterian—joined Floberg in the speakers’ area facing tribal elders, where they each read a portion of an adapted repudiation statement crafted by the World Council of Churches. Following the apology, copies of the Doctrine of Discovery were offered to the elders who were asked if they wanted to place the documents in the sacred fire. After conferring, one elder said, “This paper, these words, do not belong in a sacred fire.” They chose instead to burn the documents in vessels placed between faith leaders and tribal elders.

A Wish List for the 1 Percent

The Trans-Pacific Partnership would grant new powers to multinational corporations.

THE TRANS-PACIFIC Partnership may be the largest free trade agreement you’ve never heard of. Or if you have heard of the TPP, it’s likely due to media reports about efforts by President Obama to fast-track the agreement through legislative hurdles. Still, details of the agreement and its secret negotiation process are sparse. Were it not for released drafts of the document and sub-chapters made available by the whistle-blowing site WikiLeaks, it is likely the general public would know little to nothing of the accord.

Building on the foundation of a 2006 economic partnership agreement adopted to encourage trade between Brunei, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore, the TPP’s expansion of the agreement grows the number of participant nations to 12, adding Australia, Canada, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, Vietnam, and the United States. The combined economic force of these nations would dominate global trade, representing roughly $28 trillion—nearly 40 percent—of the world’s gross domestic product.

But the magnitude of this trading pool isn’t what concerns most critics of the TPP. What is more troubling to labor, environmental, and health groups are the powers seemingly granted to multinational corporations by the agreement and the unilateral easing of climate change laws that serve to restrain industrial nations from disproportionate consumption and pollution.

Expanded corporate powers are nothing new for international trade agreements. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) gave rise to a legal quagmire that has allowed Exxon Mobil to challenge Canadian offshore drilling regulations, Dow Chemical to bypass local guidelines to expand pesticide production and waste disposal in Mexico, and Eli Lilly to enforce U.S.-issued drug patents and prices outside the country. Previously, under World Trade Organization treaty guidelines, a corporate entity needed to persuade its host country to challenge the trade laws of another. Corporations could not directly litigate against a sovereign nation or its policies.

Wounded Souls

Christians have a presumption against war—as well as an obligation to help heal those who suffer its consequences.

WHEN CHIEF MASTER Sergeant Harry Marsters returned in 2008 from his time in Iraq, he knew something wasn’t right. At 54, the 32-year veteran of the Air Force—with 27 years full time in the military and the remainder as a reservist with the Air National Guard—felt that as one of the “older folks” he knew what to expect upon return from his assignment with the communications squad at the Kirkuk Regional Air Base in northern Iraq.

Marsters’ squadron trained Iraqi forces in the operation and maintenance of aerial surveillance equipment on the base, which housed 1,000 Air Force and 2,500 Army troops. As first sergeant he acted as a liaison to the Air Force troops and ensured the well-being of those stationed there. It was a job he relished, pouring care into building connections with the airmen and women, spending time with the chaplains, and coordinating recreation and morale-building activities.

Though Air Force personnel never left the base, they were subjected to the ever-present threat of randomly timed mortar rounds launched by insurgents. They also took part in nighttime “patriot details” in which Air Force personnel and soldiers lined the base’s runway as the bodies of fallen soldiers were loaded onto planes for transport back to the United States. But Marsters says he was most upset by what he felt was harsh treatment of the Iraqi nationals who came to work on the base.

“They were treated like criminals,” he says of the extensive searches and intimidation Iraqis received when going through base security. “Everyone in Iraq is not evil, bad, and nasty. It’s a very small group of people who are raising hell and trying to hurt the country. The average person is just trying to make some money and take care of his or her family.”

A Holy Land Without Christians?

Arab Christians are vital to a thriving Middle East—and their numbers are dwindling.

LIKE MANY Palestinians forced from their homes during the 1948 war, relatives of Jordan’s Sen. Haifa Najjar carried the keys to their Palestinian homes with them as they fled. These keys, passed down through generations, are powerful symbols of Palestinian ties to the land that international law considers theirs—even as their hope for return wanes.

As a Christian appointed by King Abdullah II to Jordan’s upper house of Parliament, Najjar is active in the education, environment, cultural, and legal sectors of the government. She is also superintendent of the Anglican-run Ahliyyah School for Girls and Bishop’s School for Boys in Amman, Jordan.

Within the mix of the 500,000 Palestinians who relocated to Jordan because of the Israeli War of Independence—or Nakba, “the catastrophe,” depending on who you ask—was a vocal minority of Palestinian Christians who joined their ranks with the existing Jordanian Christian community. Prior to 1948, Christians accounted for nearly 20 percent of the population of what is now Israel/Palestine. Today that figure is less than 2 percent. Even more dramatic are declines in the West Bank cities of Ramallah and Bethlehem. Christian populations are nearly extinct in these locations compared to their respective majorities of 90 and 80 percent prior to 1948.*

“They moved not as immigrants; they were initially thinking it was a temporary thing,” says Father Nabil Haddad of the Melkite Catholic Church in Amman. “It is similar to what Syrians are thinking right now when crossing the barbed wire, not the checkpoints, between south Syria and north Jordan.”