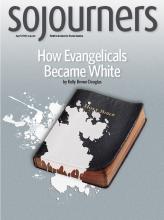

WHAT VALUES WERE really at stake for the 81 percent of white evangelicals who voted for a presidential candidate who uses crass language and admits to engaging in coarse behavior, and whose campaign was marked by vitriolic hatred of various people, particularly people of color?

I raised this question with a white male leader of a Christian foundation. In response, he told me to consider the “moral values”—such as pro-life concerns—that he said prompted, if not demanded, white evangelical support of Donald Trump’s candidacy.

The Christian leader suggested that these particular concerns mitigated any misgivings that white evangelicals might have with Trump’s dissolute behaviors and bigoted views. For many others, the moral imperatives not to support Trump were more overriding, especially for those who prioritize personal virtue as a core religious value.

The “value proposition” displayed by white evangelicals in the 2016 election, and the definition of what constitutes “moral values” and what doesn’t, is inextricably related to the nation’s upcoming demographic shift—the fact that, by the year 2044, the United States is expected to become majority nonwhite. This has significant implications for the wider faith community regarding issues of race. Much more may be at stake than the leader of the Christian foundation was able or willing to recognize.

‘The new Israelites’

The value proposition of the Trump campaign was made clear in the campaign’s “Make America Great Again” vision. This mantra tapped into America’s defining Anglo-Saxon myth and revitalized the culture of white supremacy constructed to protect it.

The Anglo-Saxon myth was introduced to this country when America’s Pilgrim and Puritan forebears fled England, intent on carrying forth an Anglo-Saxon legacy they believed was compromised in English church and society with the Norman Conquest in 1066. These early Americans believed themselves descendants of an ancient Anglo-Saxon people, “free from the taint of intermarriages,” who uniquely possessed high moral values and an “instinctive love for freedom.”

Read the Full Article