black women

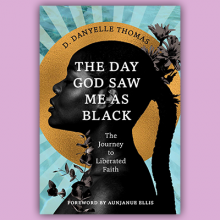

“I’LL BREAK IT down so that it may forever remain broken: Blackness is holy in and of itself,” writes D. Danyelle Thomas in her new book, The Day God Saw Me as Black: The Journey to Liberated Faith.The founder of the digital faith community Unfit Christian reflects on the ways that white evangelical theology has shaped the Black Church. She lovingly calls in the Black Church to liberate our mindsets around race, gender, sex, and sexuality.

Like Candice Marie Benbow’s Red Lip Theology (2022) and Lyvonne Briggs’ Sensual Faith (2023), The Day God Saw Me as Black reflects Thomas’ identity as a Black millennial womanist. Her experience growing up as a fat, Southern, Black Christian woman is central throughout.

Thomas expresses her love for the Black Church, even as she names all the ways it has been colonized and shaped by white evangelicalism — a Christian tradition “plagued by racism, sexism, classism, trans- and homo-antagonism, and systemic oppression.” These are the evangelical values, Thomas explains, that insisted “God is good all the time,” even amid violence and oppression, from the transatlantic slave trade to South African apartheid to the Tulsa Race Massacre.

As countless Christians have expressed their disappointment with the results of the presidential election, many have heard in response platitudes such as “God is still on the throne” or “God is not Republican or Democrat.” Zach Lambert has heard those messages before. But as lead pastor of Restore Austin, he and his Texas team took a different approach. Instead of trying to “turn eyes heavenward,” his team worked to remind their church that God was with them in their grief and struggle.

WHEN TORI BOWIE'S autopsy report was released in June, the cause of death stunned many track fans. The 32-year-old sprinter had won several medals at the 2016 Olympics. On May 2, Bowie was found dead in her apartment; the one-time “World’s Fastest Woman” had been eight months pregnant and was in labor when she died.

Bowie’s tragic death caused renewed attention to an ongoing health crisis affecting Black women in the United States. Despite being relatively young and in presumably good health, Bowie’s autopsy indicated she suffered from eclampsia and respiratory distress, pregnancy complications experienced by Black women in the U.S. at much higher rates than other demographics.

In Pregnant While Black: Advancing Justice for Maternal Health in America, Dr. Monique Rainford addresses this troubling truth: Black mothers in the U.S. are dying. They face more risks in pregnancy than white and non-white Hispanic women living in the United States.

Healing from religious harm: Why compassionate community is part of the journey.

Our country is rolling back reproductive health access in the name of “choosing life” while refusing to support life’s development in utero and post-birth. We also have not ensured that people who give birth or care for children have paid family and medical leave, workplace protections, or even access to health care facilities. In states like Mississippi and Alabama, budget pressures are forcing many rural hospitals to close, cutting off the only point of care before, during, and after labor.

“You’ve never heard of womanist theology?!” My colleague Rev. Moya Harris looked at me with a mix of excitement and incredulity. This wasn’t unusual: Through I attended parochial schools and Catholic colleges, I’m a relative newbie to the wider world of faith-based organizations and advocacy — and thus my work frequently involves googling the names of theologians, denominations, and Christian leaders I’ve never heard of before. I love this environment of continued learning, but when I learned about womanist theology, I realized I had been missing a key element of my faith: the liberatory and healing nature of God.

CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER Ella Baker utilized the strength of her voice at the height of that movement to fundamentally question the notions and ideas of equality and leadership in this nation. In 1969, Baker said, “[T]he system under which we now exist has to be radically changed.” This means “facing a system that does not lend itself to your needs and devising means by which you change that system.”

Black women have long been considered the backbone for civil rights, social justice, church advancement, and animators of democracy in the United States. If this is so, then why are so many still overlooked for advancement in political power as well as the everyday jobs that they are more than qualified for?

While “women” won the right to vote in 1920, Black women fought for about another half century to exercise their right. The inequities of gender, race, and access are still with us — and there is no greater time than now to push hard for political and social advancement.

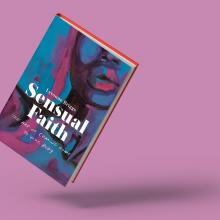

HAS RELIGION ALIENATED you from your body, demonized your sexuality, or caused you to see your body as a source of shame? If so, it’s time to come home. In Sensual Faith: The Art of Coming Home to Your Body, body- and sex-positive pastor Lyvonne Briggs invites Black Christian women and femmes to reconnect with and feel at home in their bodies, sexuality, and sensuality: “You see, Sis, home is not an address; home is where you feel safe.” Finding home in our bodies is important because, all too often, Christian spaces have deemed our bodies “temptations” and our bodily processes “nasty.” And historically, American society has tried to control Black women’s bodies and sexualities, denying our humanity and womanhood through slavery, sterilization policies, and degrading stereotypes such as the asexual Mammy and the hypersexual Jezebel. So, the type of bodily reclamation Briggs writes of is an act of personal and societal justice.

Similar to theologian Candice Marie Benbow’s Red Lip Theology (2022), Sensual Faith is a womanist work that centers the experiences of Black women of faith. “Womanism” is the term coined by writer Alice Walker in the early 1980s to honor the experiences of Black women, who were often overlooked and excluded by the feminist movement. By utilizing a womanist interpretation of the Bible, Briggs challenges harmful religious messages around women’s bodies: “Womanism says: Your sexuality is a sacred gift. Your body is holy. Just as it is. Pleasure is your birthright.”

MUSIC IS MY safe space. When all hell is breaking out, I can put in my AirPods and turn on part of the soundtrack of my life and reset. The pandemic created a chronic hell that illuminated oppressive forces that have existed for centuries. Music became even more essential for my survival.

I am a Black clergywoman who is clear that “my emancipation doesn’t fit” many people’s equation. Let me say that another way: My authentic expression of self makes some people uncomfortable. My unapologetic expression of womanist Blackness often sheds light in the shadows of a corrupt world.

I won’t pretend that I have always felt free to be me. It took a pandemic to give space to be reminded by theologian and prophet Lauryn Hill that “deep in my heart, the answer, it was in me.” Hill’s lyrics and very existence compelled me to “[make] up my mind to define my own destiny.”

Some consider Hill to be one of the greatest lyricists of all time. An eight-time Grammy winner (with 19 nominations), she sings, raps, and acts. She is hip-hop royalty. In the ’90s, I wanted to be her. She wore the dopest locked hair style, had the most beautiful brown skin, and expressed her Blackness with boldness and class. She had, and still has, a lyrical flow that men and women couldn’t ignore. She was fly. (Translated as cool, sexy, smart, and stylish.)

Her industry-shaking debut solo album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, released in August 1998, will stand the test of time. Hill speaks truth in ways that penetrate the soul. I was a young mother when the album came out. She articulated things that only a Black woman could identify with. She spoke of the tension and beauty of having a child when society was telling her that motherhood and a career couldn’t coexist. She sang and rapped about self-respect, love gained, and love lost. This album is life. This album ministers. This album is sacred.

Charismatic leaders such as Jean Vanier can inspire and transform us. But when these leaders commit abuse, how do the movements they ignite pick up the pieces?

Given widespread efforts to erase or whitewash parts of U.S. history — as school board meetings across the country become battlegrounds over what and how the next generation will be taught that history — Black History Month serves as a corrective to ensure our understanding of history includes the good, the bad, and even the ugliest parts. While the history of Black people in the United States should be studied year-round, February — which every president since Gerald Ford has proclaimed as Black History Month — also presents a critical opportunity to celebrate the contributions of Black Americans proactively, honestly, and specifically.

A FEW YEARS ago, an acquaintance and I found ourselves debating the value of art in a capitalist society—a suitably light topic for a summer evening. My companion believed strongly that art must explicitly denounce the world’s injustices, and if it did not, it was reinforcing exploitative systems. I, ever the aesthete, found this stance reasonably sound from a moral perspective but incredibly dubious otherwise.

Then, as now, I consider art’s greatest function to be its capacity for expanding our conceptions of reality, not simply acting as moralistic propaganda. After all, the foundational thing you learn in art history is that the first artists were mystics, healers, and spiritual interlocutors—not politicians.

We started making art, it seems, to cross the border between our world and one beyond. Prehistoric wall paintings of cows and lumpy carvings of fertility goddesses serve as the earliest indications of our species’ artistic inclinations, blurring the lines between religious ritual and art object. Even as the world crumbles around us, I am convinced we must hold onto art’s spiritual properties rather than succumbing to the allure of work that only addresses our current systems.

Being black in America is a privilege coupled with unique challenges. The privilege is possessing a heritage authentic to only our diaspora no matter how littered and pained our history may be. As a black man, I did not understand the challenges wholly until I grew older. For black women, the challenges are similar but with added layers that exist because of our American male driven capitalistic based economic silo.

White violence in all forms must be named, particularly white, male violence.

Much more than a depiction of self-imposed self-work, Nappily Ever After, directed by Haifaa Al-Mansour, challenges viewers to wholeheartedly release the things that chain them. It is a story about rejecting whom others say we are and celebrating the person we know ourselves to be.

I READ Austin Channing Brown’s incredible book in one sitting. This is one that every black woman needs to read to be validated and every white person needs to read to receive some perspective (and empathy) that will help inform their behavior and interactions. In this short book, Brown has concisely articulated the burdens, questions, and frustrations that I find myself experiencing daily as a black woman.

Brown brilliantly navigates explaining the intersections of blackness and womanhood, the microaggressions between workspaces and social circles, and the constant fears that so many black people face around losing everything (including life) in one moment. She “goes there” by highlighting that churches can present the most danger and racism for black people, and even chooses to address the riskiest topic of them all: the immense harm that can be caused by well-meaning, progressive white people.

My bookshelf represents a poverty of influence. So for Lent, we — two white middle-class millennial women — decided to fast from white voices and white-dominated media. For 40 days, we’re committing to only read books, watch films, and listen to podcasts written or directed by women of color.

"She had to take matters into her own hands believing that if she didn’t stop her father, it was just going to get worse and eventually somebody was going to die," Ian Friedman, Bresha's lawyer, told The New York Times.

For black women, our trauma is by nature political. Our very embodiment places us in a never-ending cycle of entanglement with systems, people, and policies designed to perpetuate violence and domination.

Photo via Milles Studio / Shutterstock

I TURN ON THE FAUCET and baptize the collards under ice-cold water for several seconds. I pick the leaves apart with my 12-year-old hands, casting the stems to the side.

A few feet away, my mother reheats her coffee in the microwave and then, between sips, crumbles cornbread and chicken liver into a large, sage-colored bowl. The familiar scent of sweet potato pies dances around the kitchen, along with the unmistakable laughter of my mother on the phone with one of her girlfriends.

Later, I’ll wash and dry the countertop before anointing it with a blanket of white flour in preparation for my mother to make the rolls—my mother’s grandmother’s recipe and the most relished part of the Thanksgiving and Christmas meals. To this day, my mother is one of a few family members who has recorded the secret, something she has always carried with pride.

Some of my first memories about food are stories like this one, at home with my mother conjuring her magic in the kitchen, creating something wonderful out of simple ingredients, as is our legacy as black women. Her food was more than just food; it was nourishment.

Before seminary, before I found language for my womanist theology and politics, before Trayvon Martin and Renisha McBride ushered me into the movement, my hands were actively developing the muscle memory that would later fuel my healing. It took me 15 years to realize that during those times in our kitchen with my mother, I was developing practical tools for my own survival and healing: cutting, peeling, dicing, skinning—not just kitchen duties, but small acts of self-determination.

My addiction to ‘non-food’

I began eating food in secret in high school, mindlessly devouring mini Snickers bars, ice cream, pizza rolls, and French fries in the parking lot at McDonald’s as a way to comfort myself and to avoid what I was truly feeling. When I was stressed or feeling depressed about school or what was going on with my family, I would stuff my face with junk food, making sure to hide the wrappers beneath my mattress.