racial justice

THESE BOOKS ALL circle the same question: What does our faith call us to do in the face of injustice? Women Talking, the 2018 novel by Miriam Toews that kicks off this list, captures the urgency of that inquiry.

“We are wasting time ... by passing this burden, this sack of stones, from one to the next, by pushing our pain away,” says Greta, a character eager to face a great evil happening in her Mennonite colony. “We mustn’t play Hot Potato with our pain. Let’s absorb it ourselves, each of us, she says. Let’s inhale it, let’s digest it, let’s process it into fuel.”

The last 25 years have dealt us plenty of pain—the so-called war on terror, racialized police violence, white Christian nationalism, greed-accelerated climate change. These books have helped us process that pain into fuel for change.

SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGISTS USE the term “infrahumanization” to describe the subtle belief that some people are slightly less human than others. This belief is particularly insidious because it goes beyond the scope of individual prejudice and affects how we see entire people groups.

We see this “less human” bias shown in the news cycles focused on the trauma in Gaza. While many of us are dismayed by news reports, we might also subconsciously believe that Palestinians grieve the loss of children and loved ones a little less than we do.

Here in the United States, some medical professionals falsely believe that Black women have a higher pain tolerance. This bias can lead to devastating medical neglect, as Black women die giving birth at a rate two to three times higher than that of white women.

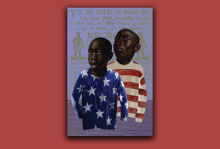

When a Child Sees War

Adapted from Alexandra Fuller’s memoir, Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight centers 8-year-old Bobo’s life on her white family’s farm in what is now Zimbabwe at the end of the wars for independence and racial equality. We see both sides of the war through Bobo’s eyes. Sony Pictures Classic

An introduction to the June 2025 issue of Sojourners.

Early in The Book of Belonging, a long-anticipated children’s story Bible, author Mariko Clark includes this paragraph: “Think about how cozy and special you feel when someone asks you about your day or wants to learn more about your favorite foods or hobbies. God made us to belong with God! That means God wants to be close and cozy with us. So all questions are welcome!”

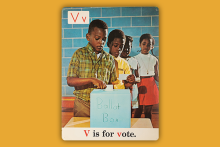

I PROUDLY SHARE the legacy of generations of people who fought to be respected as full citizens in America. I am the granddaughter of Mississippi sharecroppers. My parents picked cotton growing up, sometimes missing school to ensure the family could make ends meet. My parents left Mississippi in the late 1960s after college, having never voted. I know too well about voter suppression and the horrors of Jim Crow. The fundamental right to vote is close to my heart; it’s personal.

My generation was the first in my family born with full voting rights. I never thought the precious right to vote would be jeopardized in 2024. Yet, because the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013, the right of full and safe access to the ballot box is again impeded. Voter suppression has again taken hold as a tactic for dismantling democracy. The ghost of Jim Crow keeps on haunting.

Editor’s note: A version of this article first appeared on sojo.net on Jan. 9, 2024 as “What DEI Trainings and Evangelical Retreats Have in Common.”

JONATHAN TRAN TELLS a story he encountered while researching his book Asian Americans and the Spirit of Racial Capitalism, about Chinese immigrants who lived in the Mississippi Delta during the Reconstruction period. After the Civil War, Tran says, white people not only prevented Black people from living in certain neighborhoods and attending schools with their white children — they discriminated similarly against people of Chinese descent.

But dissimilar to the Delta’s Black population, the Chinese immigrants were able to open modest grocery stores, which allowed them to accumulate wealth thanks to Black patronage. In this way, the Delta Chinese immigrants saw their material conditions improve — but this improvement came under a system of white supremacy, which necessitated the exclusion of the Delta’s Black population.

Tran tells this story to demonstrate the ways that capitalism and white supremacy have become intertwined. In a nod to the Black radical tradition, Tran refers to this system as racial capitalism. The account also demonstrates Tran’s commitment to storytelling. He doesn’t explain the negative effects of racial capitalism in a removed or abstract way; rather, he leans into the complicated histories that have pitted racially marginalized groups against one another.

Tran, an associate dean of Baylor University’s Honors College and an associate professor of theology, understands how stories are influenced by material reality — which is why, for Tran, criticism of racism that does not also include a critique of the capitalist system is wrong-headed. But Tran doesn’t just critique racial capitalism or anti-racist enterprises that avoid economics. Tran believes that Christian theology offers an alternative story to racial capitalism, one that finds its locus in the “divine economy.”

Tran talked with sojo.net associate opinion editor Josiah R. Daniels last fall about Christian theology, anti-racism, W.E.B. Du Bois, and what it means to live into a reconstructed reality. — The Editors

One of the most troubling statistics in the country — the United States’ skyrocketing maternal mortality rate — isn’t much of a mystery to those who work in labor and delivery rooms. Underfunding, gaps in health care coverage, and hospital closures all contribute to the health care system’s state of crisis: When resources are stretched thin, birthing people, particularly Black and Latino people, and their babies don’t get the care they need.

In a Cleveland neighborhood, a set of 25 young trees line the space between the sidewalk and the road. The trees were planted by volunteers from Calvary Reformed Church in 2019, an example of the types of actions that churches can take to address rising heat in their neighborhoods. Now, thanks to 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act, nearly $1 billion will fund similar projects across the nation.

Director Jeymes Samuel’s newest movie, The Book of Clarence, is not just a biblical epic but a Black biblical epic.

“Something I often heard was that ‘there’s not enough Black Catholics.’ [That] the numbers of Black Catholics are not big enough to justify doing a survey into this community. But that was in complete contradiction with what I was seeing when I was at these rallies and with people who were engaging with the Black Lives Matter movement.”

Professor Sam Joeckel’s 21-year tenure at Palm Beach Atlantic University ended after a single complaint from a parent who stated that Joeckel was indoctrinating his students. What started out as a typical day in February soon became a nightmare for Joeckel as the dean and provost of the university waited for him outside his classroom to inform him his teaching contract wouldn’t be renewed.

A Black church in California has set out to develop a microgrid that could generate up to $1 million annually. The project, spearheaded by Gemini Energy Solutions and Green The Church, is part of a larger effort to empower Black churches — and their communities — to join the clean energy movement.

Tamice Spencer-Helms shows how colonialism and white supremacy are embodied in a Jesus made in Christian Europe's image.

MY DAD HAD a very mixed relationship with America. Based in his experience of and feelings concerning white supremacy in America, I was never sure he loved America and knew with certainty that he hesitated to call it “home.” America was never holy ground for him.

On Jan. 6, 2021, while I was watching the Capitol insurrection on TV, he died in his hospice bed. My screen view of the Capitol mob’s recitation of “hang Mike Pence,” in rhythmic incantation to bring forth the blood-boiling hate, was reminiscent of the ritualistic lynching of thousands from 1870 to 1940, particularly and almost exclusively African Americans.

I also had a screen view of my dad. Given the threat posed by COVID-19 exposure upon his chemotherapy-treated and compromised immune system, we were not able to visit him as we would have liked. My sister had installed a camera system to get a visual. I noticed that he was not moving. I earnestly studied his lack of motion and noticed that his mouth was wide open. This was the death posture. I instantly knew he was gone.

Trying to come to grips with the death of my father, while staring with glazed-over eyes at the Capitol riot, I said to myself: “The insurrection took my dad out of here. He had enough of white supremacy in America.” During the chaos of the insurgency, my dad became an ancestor. In the stark reality of his death, I realized he had been in search of holy ground for a long time.

Sometimes our nation and world are so full of injustice, loss, and pain that words fail us and our spirit can find no rest. We don’t even know what to say, how to pray, and where to begin to set right the many things that are so overwhelmingly wrong. The vicious murder of Tyre Nichols feels like one of those moments.

IN JULY, Lee Bennett Jr. stood at the podium of the Gaillard Center in downtown Charleston, S.C., as part of a three-day bicentenary commemoration of Denmark Vesey — a free Black man who had planned what could have been the largest organized resistance by enslaved people in U.S. history. Bennett brought both American history and personal history with him that day: The space where he spoke used to be his own neighborhood. There are some places where the veil between past and present feels especially thin.

The next day, Bennett offered me a tour of Mother Emanuel AME Church, where he is the historian. He spoke about Vesey, a founding member of Hampstead AME Church, established in 1818. In 1822, Vesey was arrested and executed, along with 34 others, for his plan to liberate the enslaved people of Charleston. Later that same year, a white mob destroyed Hampstead Church. By 1834, the city of Charleston made it illegal for Black congregations to meet, pushing the congregation to gather in secret until after the Civil War. In 1865, they came out of hiding and took the name Emanuel, “God with us.”

IN HER BOOK The Great Emergence, the late Phyllis Tickle pointed out that the church undergoes a “rummage sale” about every 500 years in which dominant forms of its spirituality are displaced from prominence by newer forms of spirituality. It’s much like a purge one would have when decluttering a home or preparing for a move. Older forms of spirituality aren’t done away with; they simply are no longer dominant. New things come to the forefront.

By the fourth century, the locus of Christianity had shifted from ancient Israel and Syria to a Christendom based in European and Western civilization (though a thriving Eastern church remained and does so today). About 40 years ago, another shift occurred. Now there are more Christians in the Global South than in Europe and North America. And Christianity continues to wane in the West. To the extent Christianity has accompanied colonial expansion, I believe this too is a kind of purging. Many of us wrestle with church doctrines and practices that have been in service to domination power for a long time but are untenable in a just world. Who God needs us to be today is markedly different from whom we’ve been in the past.

This month’s texts call to mind the words of the liberation song: “They say that freedom is a constant struggle. Oh Lord, we’ve struggled so long, we must be free, we must be free.” Freedom is not a static destination. Freedom must be maintained, much like the state of a house. Whatever God is calling us toward today, it won’t be necessarily familiar or even pleasant, but it will make us free.

“PRAYER AND PROTEST are not two different things.” Princeton Theological Seminary professor Keri L. Day’s proclamation—part of a rousing sermon she preached on the first day of Black History Month—provoked applause and amens from students gathered for worship in the newly renamed Seminary Chapel.

These seminarians recognized the truth of Day’s words because they had galvanized a prayerful protest to change the name of what had been known—for 129 years—as Miller Chapel. The building name honored Samuel Miller, a white Presbyterian minister who in 1813 became the second professor at Princeton Seminary. Like many of the institution’s founders, Miller preached “the enormity of the evil” of chattel slavery yet opposed the movement for immediate abolition. Miller was also an enslaver who held a number of people in bondage during his tenure at the seminary. Miller believed that Black people “could never be trusted as faithful citizens.” He played a key role in making Princeton Seminary the unofficial theological headquarters of the American Colonization Society, formed in 1817 to send free African Americans to Africa as an alternative to multiracial democracy.

Recently the seminary has begun to reckon with this past. In 2018 the institution published a report documenting and confessing its sinful “connections to slavery.” In 2019 the board of trustees made a $27.6 million investment in a range of initiatives that seminary president M. Craig Barnes characterized as “the beginning of our community’s journey of repair.”

The permanent shiny smudge replaced his bronze face,

his features fade in rusted pictures

I play with pigeon feathers picked from pages

on pulpit splinters that bear his cross of puzzled words.

Warriors unite rage, usher 10% offerings

to dear Black children morning, school wombs empty

Sheets untie laid to rest over waving hands

and church pews ready to fly away with sermons