racial justice

When we’ve decided to call ourselves woke, we are disregarding the journey of becoming woke along the way. When we say we are already decolonized, we are neglecting the seriousness of the journey toward decolonizing in all its complexities.

Kanye West draws upon the storied history of black communal worship and gospel music.

It's impossible to use the language of lynching without calling to mind horrors like those visited upon George Taylor.

A racial leveraging of forgiveness followed Amber Guyger’s trial in Dallas.

Much like Isaac from the book of Genesis, I am the son of a family seemingly destined to transience.

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was one of the worst environmental justice disasters in modern U.S. history. It was also one of the first times that I, then a teenager, consciously connected animal justice and racial justice. Kanye West’s declaration “George Bush doesn’t care about black people” is often remembered as the statement on racism in Katrina, but another expression that needed no words circulated among black people in the hurricane’s immediate aftermath: a picture of pets being evacuated on an air-conditioned bus.

While black people were abandoned, dead, and dying on rooftops, corpses floating bloated in flooded streets, people’s pets were evacuated to safety.

Black people have long understood as racist the disparate treatment of nonhuman animals and black people. In 1855, Frederick Douglass wrote that “The bond-woman lives as a slave, and is left to die as a beast; often with fewer attentions than are paid to a favorite horse.

Because of this immense history, power, and influence despite generations of ill treatment and racism, black churches need to thrive, continuing to speak truth to power and serve black communities beyond the sanctuary.

To mark the anniversary of Juneteenth, when enslaved people in Texas finally learned about the Emancipation Proclamation in June of 1865, the House Judiciary Committee held a special hearing on reparations for slavery this week. When asked about the idea of addressing the generational inequalities created by centuries of governmentally sanctioned white supremacy, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) responded that America fought a civil war, passed landmark civil rights legislation and elected its first Black President to address the “original sin” of slavery. As far as he is concerned, the sins of the past can be forgotten.

Unless the money that will be made from marijuana’s federal legalization is used for robust community reinvestment in affected residential communities across America, it fails the moral litmus test of social justice and pumps oxygen into racial wealth disparities. Without this reinvestment, America will once again be blowing smoke into the face of those who have historically been most victimized by the criminalization of marijuana. The abovementioned federal legalization proposal includes the development of a community reinvestment fund to specifically benefit communities most ravished by the marijuana ban, and the decades-long failed war on drugs. The architects of the bill outlined some potential funding areas: job training, post-incarceration and expungement services, public libraries and community centers, youth programming, and health education.

I watched Ava DuVernay’s Netflix series When They See Us and found myself angered by the people and systems that had a role in the incarceration of five innocent boys. The Central Park Five, Raymond Santana, Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Yusef Saalam, and Korey Wise, were wrongfully convicted and later exonerated of a variety of charges related to the rape and assault of a white female jogger in 1989. While the series itself honors the stories of the Central Park Five, in choosing to title the series When They See Us, DuVernay invites us into a broader conversation on the criminalization and mass incarceration of young boys and girls of color, and challenges us to define our own role within this system.

SUMMER SIGNALS FREEDOM. If you are anything like me, two words in particular shimmer with the season’s promise of boundlessness: Summer reading.

At the beginning of Black History Month back in February, however, I decided to restrict my reading for this year. Some friends and I embarked on what I christened a “Year of Reading X”—a year of reading only, or mostly, books by black, Latinx, Asian, Indigenous, and other authors of color.

While recent discussions around the whiteness of the publishing industry and Western canon have motivated many to make racially aware reading commitments, exclusively reading black authors or authors of color is not novel. People of color have long been aware of the whiteness of the conventional literary world and have negotiated it accordingly, finding and creating our own spaces. What sparks my year of reading, then?

The 39-second cellphone video shot by Bland remained in the hands of investigators until the Investigative Network obtained the video once the criminal investigation closed. Bland’s family said they never saw the video before and now call for Texas officials to re-examine the criminal case against the trooper who arrested Bland, which sparked outrage across the country.

TO MOST WHITE AMERICANS living today, racism has—until recently—managed to keep itself somewhat hidden. For decades, white people perpetuated the myth of an unbiased meritocracy, lauded laws that officially criminalized segregation and discrimination, embraced a token form of multiculturalism, and accepted a tincture of color in their overwhelmingly white world of power.

When Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, the United States tipped but didn’t topple. Klan Wizard David Duke ran for national office several times but never won. Two generations after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the country elected a black president. For 40 years, if you believed you were white, you could act as though the lie of skin superiority was largely a relic of the past.

Racism and white supremacy sold the same lie the devil wants told about all manner of evil: Look at the light; there is nothing in the shadows. All is well, move along.

We know the sentiment better, perhaps, from the 1995 film The Usual Suspects, in which it is said, “The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.” The poet Charles Baudelaire, however, first came to this idea in his prose poem “The Generous Gambler.” The narrator of the 1864 poem spins a tale of an evening spent with the devil. They drink and gamble, the devil wins, and the narrator loses his soul. The night ends with the narrator alone in his bed, begging God for mercy.

THOMAS KUHN INTRODUCED the term “paradigm shift” into common parlance in the 1960s. New paradigms teach us to see the world differently. When we receive a new paradigm, all the data flees the old one and settles into the new. For Kuhn, the classic example of a paradigm shift is the way Copernicus’ solar-centered model of the world displaced Ptolemy’s Earth-centered theory during the European Renaissance.

I knew all of that. But when Irish poet Micheal O’Siadhail referred to Copernicus as “Copernik” in his recent release, The Five Quintets, it set me toward a new thought. “Copernik” (first name Nicolaus) sounds a lot like “Kaepernick” (first name Colin).

It followed for me that Copernik (with his solar-centered hypothesis) and Kaepernick (with his refusal to stand during the national anthem at NFL games) were up to the same thing. Both performed new paradigms. While Copernik’s is now settled theory, Kaepernick’s remains highly contested. It is, moreover, highly contested precisely because it is a new paradigm that threatens everything invested in the old paradigm.

The old paradigm, so treasured in the NFL, consists in a drama of violence, money, and sex (covered by pseudo-nationalism). It provides for rich white “owners” to stage violent struggles between mostly black players. That old paradigm requires black players to conform to the ideology of white owners who use the U.S. flag to legitimate their enormous wealth and control, as if these were somehow patriotic. And because the liturgy of sex-money-violence-nationalism has become so ordinary and routine, no one notices it—exactly how the owners prefer.

Now comes Colin Kaepernick with a new paradigm that asserts that black players are free agents who are not “owned” and who do not need to participate in, collude with, or endorse the owner’s ideology.

IF I WERE MURDERED TODAY—say, shot and killed while walking unarmed through a residential area, wearing my hoodie—and my murderer weren’t arrested by dawn, my family would make one phone call. To Benjamin Crump.

This has become the African-American family emergency plan—set in motion when the “hurricane” is a white person with a gun. Call Benjamin Crump.

This is what Trayvon Martin’s family did in 2012 when they realized the criminal justice system would not punish the man who killed Trayvon. They called the lawyer who once stood on the steps of a courthouse where two white men had just been acquitted of beating to death a 14-year-old boy and said: “You kill a dog, you go to jail. You kill a little black boy, and nothing happens.” They called the attorney who, time and time again, tries to make something happen. They called Benjamin Crump.

In Trayvon’s case, Crump, one of the best-known civil rights attorneys practicing today, thought at first that something would happen without his help—since the only thing Martin had in his possession when George Zimmerman shot and killed him was a can of fruit juice and a bag of Skittles. When Crump realized there was a strong possibility that justice would not be served, he came face-to-face with what he calls “a test from God.”

“Nobody was watching this call between me and this brokenhearted father, save God,” Crump told Sojourners in a phone interview in October. “And I believe God was testing me to see if I was going to answer the bell, use the blessings and education and all the other things [God] has given me to be a blessing to the least of these. I stepped out on faith to do the right thing. And God took over from there.”

SEVEN YEARS AGO this month, Trayvon Martin, an unarmed 17-year-old high school student, was shot and killed while visiting relatives in Sanford, Fla. After George Zimmerman’s 2013 acquittal for Trayvon’s murder, I wrote about what it meant to me, particularly as a father.

I wrote about the fundamental injustice of a system and a nation in which a teenage boy like Trayvon could be killed as a direct result of being racially profiled, and his killer not held accountable, while my own teenage boys would never need to fear that a stranger would target them due to their race:

If my white 14-year-old son, Luke, had walked out that same night, in that same neighborhood, just to get a snack, he would have come back unharmed—and he would still be with me and Joy today. But when black 17-year-old Trayvon Martin went out that night, just to get a snack, he ended up dead—and is no longer with his dad and mom. Try to imagine how that feels, as his parents.

Martin Luther King Jr. said in his “I Have a Dream” speech, “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” King’s dream failed on Feb. 26, 2012, when George Zimmerman decided to follow Trayvon Martin because of the color of his skin. Racial profiling is a sin in the eyes of God. It should also be a crime in the eyes of our society and in the laws we enact to protect each other and our common good.

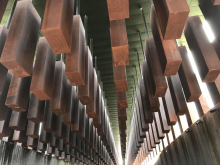

I have met Silence. The ghostly silence of dust balls and mites, of cobwebs and sunbeam shadows in the cold crumbling cubicles off the Liberian coast where African persons spent their last nights and then lost sight of their land forever. I have felt the stony silence of apartheid era prisons in Johannesburg and Cape Town. I have seen the nostalgic silence of colonial desolation on the Harare Kopje, in Zimbabwe. But this silence at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is like none other. A requiem.

Twenty-seven years ago, as an African-American female clergy leader and legislative advocate, I operated in two worlds dominated by male power – religion and politics. I watched Anita Hill sit with the same quiet dignity as Rosa Parks resisting racial segregation on an Alabama bus by refusing to give up her seat to a white man. Rosa Parks went to jail. Anita Hill watched as Clarence Thomas was voted onto the U.S. Supreme Court. For both women, it looked like the dominion of male power had won.

MacArthur, at least as I remember him, is not a bitter old man. But he sure sounds like one in his blog series, “Social Injustice to the Gospel.” In fact he sounds exactly like my grandfather who repeatedly says, “I don’t see why everything has to be about race all the time."

Why is diversity essential for the educational mission of U.S. universities? Advocates for diversity in higher education emphasize a variety of reasons. They range from business oriented considerations, like the need for a diverse and well-educated workforce to meet the needs of an increasingly diverse marketplace or the belief that diversity fosters innovation and creativity.