Technology

From 2023 to 2024, I served as a Jesuit Volunteer with the purpose of helping educate high school students. I was repeatedly left awestruck by how easily young people today become dependent on and how effectively they can navigate online spaces.

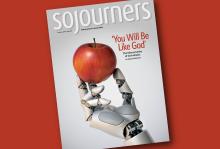

The most terrifying thing about power isn’t the force it applies; it’s the moral vacuum it creates in the soul of the person wielding it.

I think of the times I’ve made choices that were professionally powerful but ethically hollow—the quick decision that saved time but neglected a vulnerable party, the project that elevated my status but buried someone else’s contribution. We’ve all been Victor Frankenstein, playing God with a Promethean flame, only to be horrified when the fire scorches someone else.

As the ubiquity of artificial intelligence grows, Black spiritual leaders find themselves navigating its perils and promises.

Amid ethical concerns over the sourcing of AI materials, the role of technology in creative endeavors, and the environmental consequences of AI, there’s a significant demand for the technology among church leaders. A 2024 survey by Barna Group found that 78% of pastors are comfortable using AI to assist with marketing and that 58% of pastors are comfortable using AI to assist with communication.

Rev. Heber Brown III, founder of The Black Church Food Security Network, interprets this demand as a symptom of increasing workloads.

Corporations are jamming AI into every platform we use. Like it or not, it’s clearly here to stay. But we can fight back the mass possession of AI demons. By learning how AI works and why it has such a hold on us, we can start to see through its demonic facade. But that’s not enough by itself. To bust these ghosts for good, we need to think bigger and find collective ways — like trade unions — to take control of our work and thinking.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IS all the buzz as I write this. It’s been impossible to ignore the omnipresent chatter about AI, from the deluge of online commentary to congressional hearings. As I thought about adding to the chatter — er, providing some insightful perspective from a progressive theological point of view — I wondered what more could be said. So, I decided to ask AI. I prompted Microsoft’s Bing AI chatbot to draft an essay, “from a progressive Christian perspective,” on the dangers of AI. The first line of the response: “As an AI language model, I am not capable of having a religious belief or point of view.”

Well, that’s reassuring.

Concerns about AI aren’t new — science fiction writers have painted grim pictures of machine consciousness at least since Samuel Butler’s 1872 novel Erewhon (wherein Butler wrote in his three-chapter “The Book of the Machines” that “there is reason to hope that the machines will use us kindly, for their existence will be in a great measure dependent upon ours; they will rule us with a rod of iron, but they will not eat us.” One hopes that we’ll find better reasons to hope.). Warnings of apocalyptic totalism abound: In May, Matthew Hutson wrote in The New Yorker, “In the worst-case scenario envisioned by [artificial-intelligence doomers], uncontrollable AIs could infiltrate every aspect of our technological lives, disrupting or redirecting our infrastructure, financial systems, communications, and more.”

Since the Bing chatbot is incapable of offering a theological perspective, I asked scholar Walter Brueggemann for his thoughts.

“MACHINES, WHETHER MECHANICAL or digital, aren’t interested in truth, beauty, or justice. Their goal is to make the world a more efficient place for more machines.” So argues journalist Andrew Nikiforuk, paraphrasing Jacques Ellul’s seminal The Technological Society. “Their proliferation combined with our growing dependence on their services inevitably led to an erosion of human freedom and unintended consequences in every sphere of life.”

THE MET GALA is fascinating. Part chaos and part fundraiser, the Gala has created a treasure trove of cultural touchstones and meme-worthy content over the past few years. Created in the 1940s to benefit the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, the Gala is, at its core, a paean to the sartorial arts. In many ways, it’s the gift that keeps on giving, especially if you, like me, are not opposed to a lot of pomp and very little circumstance. However, in the thick of my 2 a.m. behind-the-scenes-at-the-Met video binge, a thought occurred to me that I’ve been turning over ever since: America may not have bread, but it sure has circuses.

MAPS ARE NOT just drawings of a place; they are also windows into a perspective. In the era of European colonial expansion, maps were essential tools.

The 15th century imperial edicts known collectively as the Doctrine of Discovery theologically and politically justified the brutal seizure of land not inhabited by European Christians. This set into motion a new worldview that is the basis for all modern property ownership and established a relationship to the land based on colonization rather than habitation. As a result of this and other political arrangements, the Roman Catholic Church controls about 177 million acres of land around the world.

Molly Burhans is a Catholic, an activist, and an entrepreneur. She is also a cartographer and geographic information system (GIS) analyst who sees the church’s landholdings as an opportunity for a global spiritual and ecological transformation. If church maps in the past too often represented cultural oppression and land domination, the maps Burhans creates are powerful tools for ecological regeneration and social repair.

IF ASKED “What era would you time travel to if you could?” many young Black and brown and Indigenous people would answer in a flash, “None of them.” Why? We’re too aware of the past and what it means for us today—we tweet about the results of American slavery and can break news of the latest injustice to emerge from centuries-long hatred of nonwhite skin faster than MSNBC. We feel the negative effects of history enough each day to not want to go back there.

But maybe we should. If all we see of ourselves on TV and social media is us sick, oppressed, or dead, what other understanding of ourselves do we miss? How can we remember that we are greater than the damage done—that our history holds more than that and so might our present?

Ruby Sales, founder and director of the SpiritHouse Project, helps young people invested in faith and social justice see themselves through the lens of their divine wealth and boundless potential rather than through eyes dimmed by media and versions of history shaped by white supremacy. Sales, who by age 17 was a Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee member registering people to vote in her home state of Alabama, has a Master of Divinity degree from the Episcopal Divinity School and is a preacher, speaker, and intergenerational mentor on racial, economic, and social justice. I spoke with her in December by phone. —Da’Shawn Mosley

Da’Shawn Mosley: I watched a YouTube video of you speaking in 2015 at St. Albans Episcopal Church in D.C. and was struck by what you said about today’s youth: that the most recent generations have incredible insight but haven’t lived enough to have hindsight.

Ruby Sales: Now that I’m working with young folks in my fellowship program and have had some time to weigh how things have changed from the ’90s to the 2000s, I think young people lack insight also. When you have been raised in a technological age, when history is no longer lived experience but is created on social media and reproduced through technology, I think that long-term memory is affected, as well as the ability to empathize and connect with human suffering. There is a difference between being able to theorize about human suffering and being able to feel it. All of these are challenges faced by generations raised in a technocracy—the decimation of history, of who we are as a people.

FOR OVER A month now, like everyone else, I have been isolated at home. Here with me are my wife, Polly, and our two youngest sons, both college students. All of us are continuing our work and studies online, and our rural home has become a sort of cyber-monastery. We meet in the morning for daily Mass on YouTube, then peel off to our separate hotspots to toil through the day. We don’t have compline, but we do often reconvene to watch The West Wing.

This isn’t the life any of us would have chosen, but it’s probably good for the soul to surrender some of our precious, almighty power of choice, and it helps that almost everyone is going through this with us. But there’s one aspect of our locked-down life that we can’t attribute to the vagaries of a random virus, and it isn’t shared with most of our fellow citizens. Instead, it’s one of the many rank inequalities the COVID-19 crisis has exposed in American life.

Unlike most of you, we don’t have access to high-speed broadband internet. Two months ago, that might have seemed like a trivial complaint, but not now. And we’re far from alone. The best estimate says that there are about 42 million of us, about 13 percent of the U.S. population, mostly in rural America. Then there are all the people who could have access to broadband, but don’t, mostly because they can’t afford it. All told, about 30 percent of us are out here in the digital cold.

Many psychologists fear awe is receding from our lives and that a vital social resource is disappearing.

As Shamika and I called upon our own experiences in church and seminary, we became especially concerned with providing a resource for those who historically have been barred from participation at the Lord’s Table: the divorced, Christians of color, LGBTQ believers, those living far from physical community, or far from a church that is physically accessible. While we’re not trying to replace “brick and mortar” community, we believe God calls us beyond a spirit of fear in the face of innovations in technology.

As technology continues to evolve, it is rapidly outpacing the standard ethical frameworks by which we normally approach new developments. The nucleus of technology and sexuality, which was situated around questions of porn, has been forced to answer new questions, grappling not only with what is right and wrong, but why. With the rise of new, impending sexual technology, the church must learn how to speak into this realm.

BY THE TIME you read this, I will either be recuperating from multiple contusions or hugging the outer walls of buildings as I walk from corner to corner, trying to avoid said contusions. Either outcome is apparently the price we pay for progress, although I’d be happy to let another loyal citizen experience that progress. (Why should I use up my sick leave?)

My anxieties of late have nothing to do with the usual political hypocrisy that stalks the streets of our nation’s capital. I speak instead of thousands of rental bicycles and electric scooters that flit about like troublesome insects, albeit insects completely lacking in judgment and common sense. They are everywhere and, counterintuitively, can come out of nowhere. And they move with a speed matched only by the wobbliness of the inexperienced riders who thought it would be cool to “arrive in style.” Or “in ambulance,” depending on conditions.

To make matters worse, one scooter company recalled thousands of its vehicles because some were at risk of spontaneously catching fire, an extremely dangerous occurrence that would both threaten the lives of riders and look totally cool as FLAMES COME OUT OF YOUR SCOOTER! But like I said, very dangerous and, after I do it once, it must be stopped.

"WE LIVE AS if the connections provided by digital technologies are vital,” writes Gaymon Bennett in the cover story, “and indeed we have made them so.”

Guilty as charged. Hang around the Sojourners office long enough and you’ll hear stories about how we used to keep a list of our subscribers in a shoebox and write articles on typewriters. But those days are done: Today our office hosts a congregation of laptops, tablets, screens, cameras, and smartphones that we need to access databases, send messages, and update our website. When a network upgrade happens to knock out the Wi-Fi, we all go home because, well, how could we work?

Entering digital spaces that are dominated by conservative Christian resources, Our Bible App is attempting to carve out a unique space. It is explicitly pro-LGBT, pro-women and pro-interfaith inclusivity in its stated mission. “I created this app because I'm tired of feeling left out of Christianity because of my complex identities,” Crystal Cheatham, the app’s founder and CEO, told Sojourners. “I wanted worship materials that talked about an inclusive kind of faith and embraced that same kind of community.”

FRANTICALLY GRABBING last-minute items, I rush out the door to get my middle-school son to his pregame warm-up. “Oh, don’t rush; it will only take us 25 minutes to get there,” says my son. Surprised, I question where he got that information. Looking up from his phone, he replies, “Google sent a notification on my phone since my calendar has the game with location.” With some marvel in his tone, he remarks, “Every morning Google Assistant tells me how long it will take the bus to get to school.”

Humans have always shared information with each other, but the advance of digital media altered the time and geographic constraints that once shaped our historical patterns of communication. This transition ended the “Gutenberg era,” a period of human communication marked by a dependency on print, authorship, and fixity, and launched us into an era of communication marked by openness, collaboration, and easy access to information.

Despite the rapid pace at which we churn through this information, our new communication styles are also shaped, paradoxically, by permanence. Every share, post, or comment is archived, creating an online trove of information that identifies every person and their connections: where we get our news, what we look like, what sports team or social causes we support, who “likes” our church on Facebook, and, in my son’s case, our current whereabouts, our travel route, and destination points.

The internet is forever

In the world of digital ethics, the “endless memory of the internet” has recently attracted a lot of attention. How do we live in a world that increasingly does not forget?

“Fears about the technology might go viral, especially if they’re designed to go viral, but the more lasting effect might be the way this technology is adopted and adapted by creative, mission-driven people,” Silliman said.

Some Minecraft users even “build” their own religious icons. Using blocky “skins” — Minecraft lingo for a character — they create Jesuses, popes, priests, rabbis, angels, and more to populate Minecraft worlds everywhere.

For Augustine and his followers, attention was a rare and valuable experience, perhaps even more than for us since they associated it with the divine. One might expect that as a result they should have simply dismissed distraction. But they didn’t.