Poetry

Some mornings I drive to the duck pond

instead of writing poems. I can’t remember

how to keep words coupled to the truth.

So much lying has torn words loose

from what they stood for. Remember,

back when we agreed on their meanings?

I’d say honey for instance, and you could

taste it. Once you said freedom

and I saw doves rising from your shoulders.

We shared language so we were not alone.

We both loved words as if we could see them:

like ducks bobbing on a pond, dipping,

scooping, swabbing insects from the air.

I can tell from the way

they are staring at shadows on the ground

that the voice-bearers have come

from that place where

trees are not life-giving.

Two nights ago, One was here with them

Whose longing, love, and pain woke my soul,

deep-buried,

which sleeps through winter,

moth-like.

He is not here with them now.

Today, the United States and Iran are two countries on the precipice of war with ruling elites who quote Rumi.

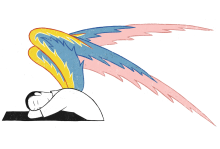

1. I knew, but didn’t know—extent, sprawl,

continent-wide bird with great shadow-wings

hovering over a whole nation’s knife-opened birth—

talons and curved-hook raptor’s beak coming

for my heart, which is history,

which shields itself and hungers

as though truth were a flock of season-following geese

from whom I choose how many to bag,

how many a season requires. So many

moments sound like gun-shot—

sound cracking the ear with its own hammer,

pummeling some dark priest-hole in every mind,

fists on doors, slammed hatches on ships,

iron coming down so hard on a deck it loses its clang,

a skull punched against echoing wood, snapped branches,

snap of a jaw-trap around leg bone.

An eagle cannot feed its young its young.

Though the inaugural Madeline L’Engle conference felt like a safe haven as we gathered in the cozy glow of art, and fellowship, we were all still very aware of a similar sense of imminent evil in our country and the world at large. We are no longer in the Cold War, but the uncertainty of the impeachment hearings, of uncontrollable wildfires at home and abroad, of the refugee crisis and the hardening of hearts at the borders hang over us daily. Just as is often asked these days about Fred Rogers, we at the conference found ourselves murmuring, “What would Madeleine L’Engle think? What would she do?”

ROSE MARIE BERGER doesn’t know it yet, but through her tour-de-force poems in Bending the Arch, she has become a holy woman of many nations. Among my own people, she would be called one of the alikchi, a sacred healer, a doctor of the people, a woman who can restore balance to lives that have been shattered. She does this through the strong medicine of words.

Berger, poetry editor and a columnist for Sojourners, describes Bending the Arch as “ethnopoetic documentary poetry.” “Ethno” because it speaks with the accents of a dozen different cultures: European settlers, Chinese miners, Native American leaders. “Poetic” because it uses a cat’s cradle of language from different moments, people, and realities. “Documentary” because it covers a vast scope of America’s manifest destiny history, symbolized by the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, which is depicted on its cover. All these are contained in layers of history, one on top of another, until the spiritual sediment of Berger’s meaning begins to become clear.

I am the border agent who looks

the other way. I am the one

who leaves bottled water in caches

in the harsh borderlands I patrol.

I am the one who doesn’t shoot.

I let the people assemble,

with their flickering candles a shimmering

river in the dark. “Let them pray,”

I tell my comrades. “What harm

can come of that?” We holster

our guns and open a bottle to share.

Save for the sun, the nearest star

is more than twenty-five million

million miles away.

What has a single star

shining in Bethlehem

to do with us?

IN 1948, A HERMIT was made known to the world by another hermit. Like many Christian holy men, the Jewish-born Catholic contemplative and poet Robert Lax had his early spirituality enshrined in a book: The Seven Storey Mountain, the bestselling autobiography authored by his friend, the Trappist monk Thomas Merton.

“He had a mind naturally disposed from the very cradle to a kind of affinity for Job and St. John of the Cross,” Merton wrote about Lax. “And I now know that he was born so much of a contemplative that he will probably never be able to find out how much.”

Better known to many for what was written about him than for what he wrote (and he wrote a lot), Lax, who died in 2000 at age 84, wanted, according to his archivist Paul Spaeth, “to put himself in a place where grace can flow.” For Lax in the 1940s, New York City was not such a place. Though he worked with the poor at Baroness Catherine de Hueck’s Friendship House in Harlem, and had enjoyed jazz with Merton, he balked at the gaspingly fast pace and materialism of the city. He was also unhappily employed at The New Yorker.

LIKE MANY PEOPLE, I have spoken out more times than I can count under the literal and metaphorical banner of “Silence Is Violence,” my voice growing louder and louder in the past several years.

Yet recently, on one matter, I found myself having fewer words, not more. Gun violence rendered me mute.

The death counts that rise in real time. The fact that before we have comprehended one shooting, another has occurred. The relativizing of value and shifting calculus of loss we have begun to accommodate this “new normal.” The reality—contrary to what one would think based on media attention and political rhetoric—that mass shootings account for less than 2 percent of U.S. gun violence (suicides, by contrast, account for nearly 66 percent).

THE WORD THAT comes to mind when considering American Journal: Fifty Poems for Our Time is gift. Edited by former U.S. Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith, this anthology of poems from 50 living American poets addresses the nation with generosity. In her introduction, Smith describes American Journal as “an offering” for us to expand, renew, or establish our relationship with poetry and each other. She writes that she loves poems because they invite her to “sit still, listen deeply, and imagine putting [herself] in someone else’s unfamiliar shoes.”

American Journal presents 50 different takes on the American experience: a school field trip (“The Field Trip,” by Ellen Bryant Voigt); war (“Personal Effects,” by Solmaz Sharif); the shouldering of inequity on young, brilliant lives (“Mighty Pawns,” by Major Jackson); addiction (“My Brother at 3 AM,” by Natalie Diaz); work (“Minimum Wage,” by Matthew Dickman); language (“Music from Childhood,” by John Yau); and hope (“For the Last American Buffalo,” by Steve Scafidi).

Darling of Mayans, Incas, and Aztecs, cochineal

conquered the ever-expanding world—

borne of female coccids boiled, dried, and ground

fine as dust, then woven with water, coaxing color

vibrant as any pink peppercorn, dye so prized,

long before Spain came, natives bred the prickly pear

on which the insects fed to bear fewer spines,

so, horsetail in hand, they could brush the parasites

On the Sunday Gran died, I baptized a little girl sixteen months old. And I was grateful for the unending grace that knows neither limit of time nor space. And, as the water spilled down her rosy cheeks, I remembered how Gran held my firstborn, how Gran held me when I was a child, how I held Gran’s hand for the last time, just a few days before.

The water that gives life mixes

With the blood and the tears

From the gas, the bullets

Why wouldn’t they drop by, stare up

approvingly at the point of the minaret?

Perpetual connoisseurs of the loving work

of centuries, the stacked stones, nails pounded

until synagogues, temples, shrines

little houses of worship rise from the land.

This seep of droplets sponged by moss leaked

from a cleft in the rock; the waters in the cleft

rose osmotically from earth:

the aquifers of earth rained down

from cloudburst skies;

HUMANITY HAS BEEN reaching ever since Eve put her hand out and plucked the forbidden fruit. Since then, our acts of extension have been plagued far too often with violence and, in the end, death and despair. Philip Kolin’s new book of poetry, Reaching Forever: Poems, takes on those stretches and examines them with grace. His book is a fresh take on what it means to be loved and loving.

In the poem “God Comes to the Eternal Gate Holiness Church,” Kolin makes short work of people whose reaching is unsuccessful, via one of my favorite lines: “Bystanders down country roads reach out to him.” In other words, the spiritual life is not one for spectators but for those who do God’s will.

Writing poetry has helped me face all the fear and uncertainty that surrounds a lifelong diagnosis.

In my Mexican heaven, my grandfather's hands would be calloused from turning pages of poetry. He would be sitting at the dinner table, sipping coffee, and reading, looking up as I walked out the door to tell me “que dios te bendiga mijo.” He wouldn’t sing hymns or shout hallelujah, but every evening at the same time he’d sing the song “Gema” to my grandmother.

IRISH POET Patrick Kavanagh famously said, “Any poet worth his salt is a theologian.”

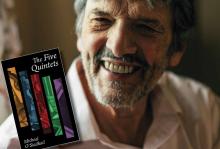

In The Five Quintets, a poetic tour de force by Micheal O’Siadhail, Kavanagh’s quip is flavorfully borne out. Quintets offers a sustained reflection on Western modernity (and its yet unnamed aftermath) in the vein of The Divine Comedy, Dante’s sustained reflection on medieval Europe (and its aftermath, the Renaissance).

O’Siadhail (pronounced O’Sheel) inspects 400 years of Anglo-Atlantic culture—artistic creativity, economics, politics, science, and “the search for meaning”—with the skillful hand of a citizen-poet, refracted through an Irish Catholic soul. Dublin born and educated, now poet in residence at Union Theological Seminary in New York, O’Siadhail embodies the vatic tradition of the Hibernian Gael—poet, prophet, priest, and, at times, jester.

His blind guide for the modern era is Madame Jazz—who encompasses klezmer from the Jewish shtetls and céilí music from famine Ireland as well. Jazz is the consummation of all that is truly human, the best of our polyphonic harmonies, a wild, joyful freedom born of shared suffering. Her chilling counterpoint, who ends the age of monarchs, is Madame Guillotine, whose shadow reaches forward into our War on Terror.