LIKE MANY PEOPLE, I have spoken out more times than I can count under the literal and metaphorical banner of “Silence Is Violence,” my voice growing louder and louder in the past several years.

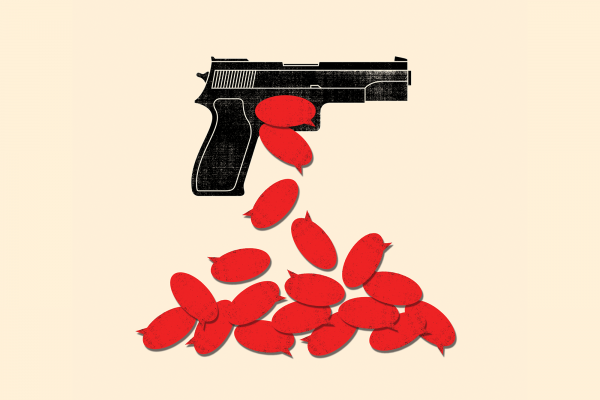

Yet recently, on one matter, I found myself having fewer words, not more. Gun violence rendered me mute.

The death counts that rise in real time. The fact that before we have comprehended one shooting, another has occurred. The relativizing of value and shifting calculus of loss we have begun to accommodate this “new normal.” The reality—contrary to what one would think based on media attention and political rhetoric—that mass shootings account for less than 2 percent of U.S. gun violence (suicides, by contrast, account for nearly 66 percent).

Ubiquitous, normalized gun violence left me wordless and weary, struggling to articulate out of a mix of rage, hurt, fear, and cynicism. I assumed this was “advocacy burnout,” but soon realized there was something more. It wasn’t simply the issue that exhausted me; it was language. I was experiencing the failure of political speech, the paucity of words—mine and others’—in the public arena. I felt the need to fall silent in search of deeper, truer expression.

I found it in language grounded by poetry. Bullets into Bells: Poets and Citizens Respond to Gun Violence contains poems accompanied by responses from gun violence survivors, family members, and activists. When I read this anthology last year, I was further stripped of speech. Its truth-telling demands that we shut up and listen and really see what is happening in gun violence. For example, in the opening of Mark Doty’s poem “In Two Seconds,” 12-year-old Tamir Rice is a sunflower whose astral brilliance, years in the making, has been suddenly snuffed out. The enormity of that collapse yields an absence not unlike a black hole: a gaping wound in time and space, a vacuum of reason.

Poems say more with less.

Prophets, I think, do the same.

Many of us are protesting today out of a strong desire for prophetic witness, an honest need for truth. Now is the time for prophets, on countless issues. My experience tells me this means listening as much as speaking out. In addition to prophets excoriating wayward kings, the Bible showcases wordlessness as a route to truth. Romans even marks it as divine, depicting the Spirit interceding for us with sighs or groans “too deep for words” (Romans 8:26).

At the end of his poem’s opening stanza, Doty rephrases as a question the words Jesus often said to close a parable: “Who has eyes to see, or ears to hear?” As in scripture, so, too, here: These words challenge, invite, direct. Jesus’ parabolic refrain asks us to cut through all the noise and tune in to a deeper frequency within the fray.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!