In my Mexican heaven, my grandfather's hands would be calloused from turning pages of poetry. He would be sitting at the dinner table, sipping coffee, and reading, looking up as I walked out the door to tell me “que dios te bendiga mijo.” He wouldn’t sing hymns or shout hallelujah, but every evening at the same time he’d sing the song “Gema” to my grandmother.

But he’s not sitting at the table. He never read poetry. And his hands were calloused from years of construction and factory work.

In José Olivarez’s Mexican heaven, the poet describes how Mexicans got in. To the doctrinal frustrations of various denominations, they were not let into heaven because of grace or good works. They were let into heaven by a man named Pedro who is no saint. But because Pedro controls the entrance, “all the Mexicans walk into heaven, / even our no-good cousins who only / go to church for baptisms & funerals.” There, the table is set with tamales, tacos, tortas, and aguas frescas. In his Mexican heaven, Jesus is not Jesus but is “Jesús from the block.” And Chuy, always the cholo, has La Virgen de Guadalupe tattooed on his back, but no one on earth cares about him or his life.

“There are white people in heaven, too” Olivarez writes. “They build condos across the street / & ask the Mexicans to speak English.” For a poet whose faith is far from certain, he writes this line with complete certainty: "just kidding, there are no white people in heaven." Presumptuous, he is sure that heaven cannot be gentrified, that the displacement of communities, the discarding of people will not continue in the afterlife — but in his experience in Chicago he knows of no other model of coexistence.

Heaven seems far away, especially when “at the border—el diablo anda suelto, / ready to rip the world from her hips,” as poet Carolina Hinojosa-Cisneros writes. There is no hope, no haven, no refuge, when the devil is on the loose in the desert, tearing children away from their mothers, putting them in cages. But the devil isn’t bright red and caped. He’s not even supernatural. He wears a dark green uniform and probably goes home at the end of a shift. While he eats dinner, weary mothers pray but their “prayers fall around like / bright marbles of misfortune.”

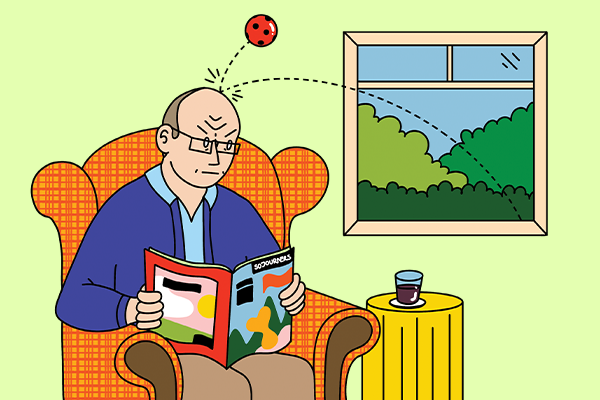

It seems that in Mexican heaven there are no saints or martyrs, just mothers, fathers, primos, who carried crosses, bore them, wore them around their necks and passed them down to us to protect us. They blessed us when we left, prayed at night when we got home, and lit candles for us to follow in the darkness. Bereft of bodies, broken and marked, they find a place where their being rests. That place does not look like heaven or purgatory. It is the impossible fantasy of a regular life. The improbable luxuries of living a life no longer under surveillance or state violence. No need to sing in a choir, when sitting in a chair will do. They are accepted. They are able to relax.

These are the words for when the church cannot supply the language for liberation. This is what it looks like when faith is challenged, but not broken. This is what faith looks like at the moment before it is lost. There is not a chasm of difference between the hopeful and the hopeless. Faith finds itself not in the trappings of the celestial and angelic, but consecrated in the quotidian.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!