Native American

“This to me is one of the most consequential things I’ve ever had an opportunity to do in my whole career,” Biden said in his apology at an outdoor football and track field in Laveen Village, Arizona, near Phoenix. “It’s a sin on our soul. ... I formally apologize.”

Across the nation, Catholic Church leaders are beginning to reckon with their institution’s role in operating Indigenous residential schools and the lasting consequences these schools left on Native American communities. One state seeing growing momentum to address this history is Minnesota, which had 15 boarding schools; Catholic groups operated at least eight of them.

A few days ago, I gathered with my two Potawatomi sons on our couch to watch Molly of Denali, a cartoon that recently premiered on PBS starring a young girl named Molly who is an Alaska Native (specifically, Gwich’in/Koyukon/Dena’ina Athabascan). This show is the first of its kind in the history of the United States.

Alaska has a “linguistic emergency,” according to the Alaskan Gov. Bill Walker. A report warned earlier this year that all of the state’s 20 Native American languages might cease to exist by the end of this century, if the state did not act. American policies, particularly in the six decades between the 1870s and 1930s, suppressed Native American languages and culture. It was only after years of activism by indigenous leaders that the Native American Languages Act was passed in 1990, which allowed for the preservation and protection of indigenous languages. Nonetheless, many Native American languages have been on the verge of extinction for the past many years.

At a time when the Trump administration has created a new task force to address discrimination against certain religious groups, the exclusion of Bears Ears and other places of religious significance from these discussions raises important questions about religious freedom in the United States and also the legacy of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act.

The Northern Cheyenne Tribe, located in southern Montana, said the administration lifted the moratorium without hearing the tribe's concerns about the impact the coal-leasing program has on the tribe, its members, and lands.

Now a tribal coalition, which considers many sites within Bears Ears sacred, fears the Trump administration will take the unprecedented step of stripping a national monument of its designation, and leave their ancestral lands vulnerable.

In one weekend, the swastika appeared in public places in three U.S. cities — Houston, Chicago, and New York. The sight was so offensive, average New Yorkers pulled out hand sanitizer and tissues to wipe the graffiti from the walls of the subway where it had been scrawled.

“Within about two minutes, all the Nazi symbolism was gone,” one subway rider who was there said. He added, “Everyone kind of just did their jobs of being decent human beings.”

The backlash to gospel singer Kim Burrell’s homophobic rant was swift: canceled national television appearances and the termination of her local public radio show.

But to those of us in religious communities, it’s important to note that, even as the controversy over Burrell’s statement recedes from the national spotlight, the issue of what goes on in the vast majority of American churches remains a festering wound.

Dec. 4 was a beautiful reminder, in the long struggle for justice, that, no matter how long we wait, God hears our cry. And love and justice will win.

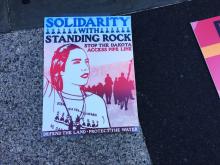

A few weeks ago, Chief Arvol Looking Horse issued an invitation to clergy and faith leaders to stand in solidarity with the people of Standing Rock. He said he was hoping maybe 100 would respond. But I joined thousands, in a procession of faith leaders, to gather around the sacred fire at the Oceti Sakowin Camp at Standing Rock.

I knew something special was happening here.

Does Pope Francis have a position on the Dakota Access Pipeline?

That’s one question he hasn’t been asked, and he might demur if pressed on such a specific issue. But in his landmark encyclical on the environment published last year, and in other statements, Francis has strongly supported arguments of the Native American-led resistance movement on three core issues: indigenous rights, water rights and protection of creation.

It’s being called “the largest, most diverse tribal action in at least a century”: hundreds of Native American tribes camped among the hills along the Cannonball River.

They’ve gathered in tents and teepees, and in prayer and protest, to oppose the construction of an oil pipeline, engaged in what both activists and religious leaders are calling a spiritual battle.

And they won a partial victory on Sept. 9, when the federal government ordered a provisional halt on construction near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation.

What’s behind the opposition to the pipeline, and what makes it spiritual?

We cannot control or shape the place of our birth. It gives us our bounds for understanding ourselves on this earth. It is difficult to grow beyond our background to include others who are different within the scope of our compassion. Most often we are inclined to feel loyalty only to people who are similar to us in critical regards.

DURING A TRIP to Alaska in September, President Obama announced that the name of Mount McKinley, the highest peak in North America, would be officially restored to Denali, the Koyukon Athabascan name that means “the tall one.” This is the name the Athabascan people have used for the mountain for centuries. “This designation recognizes the sacred status of Denali to generations of Alaska Natives,” announced the White House.

Apparently, William Dickey, a gold prospector in Alaska, coined the name Mount McKinley “after William McKinley of Ohio, who had been nominated for the presidency, and that fact was the first news we received on our way out of [that] wonderful wilderness,” Dickey wrote in 1896. McKinley was elected the 25th president, but he was assassinated in his second term, never having set foot in Alaska.

Restoring the mountain’s rightful name has been a passionate issue for Alaska Natives for more than 100 years.

A few years ago a Native elder was asked for his thoughts on the millions of European immigrants who had flooded Turtle Island, as North America is known to many Native people, to establish a new nation. “They’ll leave,” he said. “Eventually, after they have used up all the resources and the land is no longer profitable for them, they’ll leave. They’ll move on to someplace different. And then we, the Indigenous people, will nurse our land back to health.” That is an incredible perspective from a wise man who has seen the lands of his ancestors senselessly exploited by generations of foreigners.

From a Native American perspective, the U.S. is a country of more than 300 million undocumented immigrants. People from all over the world have left their lands, their homes, their families, and everything they knew and loved to come here. They flocked to this “new world” largely in pursuit of a dream of financial prosperity. But they never asked for permission to be here, nor has permission ever been given.

After over one hundred years of being known as “Mount McKinley,” North America’s tallest mountain will henceforth be officially recognized as “Denali.” President Obama announced the change on Aug. 30 in anticipation of his trip to Alaska, on which he will call for aggressive action against climate change.

Alaskan Native tribes have long objected to the cultural imperialism embedded in the name “Mount McKinley,” which commemorates a man who never even stepped foot in Alaska.

AT THE WORLD Christian Gathering of Indigenous People in 1996, our North American Native delegation was unable to find any “Christian” Native powwow music that we could use to dance to as part of our entrance into the auditorium. This was important at the time, as we didn’t feel the liberty to use “non-Christian” powwow music for a distinctly Christian event. A contemporary Christian song by a Caucasian worship leader using some Native words and a good beat was selected.

Except in a handful of cases (believers among the Kiowa, Seminole, Comanche, Dakota, Creek, and Crow tribes, to name some)—and those always in a local tribal context—Native believers were not allowed or encouraged to write new praise or worship music in their own languages utilizing their own tribal instruments, style, and arrangements.

The United Church of Christ for the mid-Atlantic region passed a resolution Saturday asking its 40,000 members not to buy game tickets or wear any souvenir gear of the Washington NFL club until it changes its embattled team name.

“I hope this debate will continue to draw attention to an unhealed wound in our cultural fabric,” the Rev. John Deckenback, conference minister, said in a statement. “Changing the name of the Washington NFL team will not solve the problems of our country’s many trails of broken promises and discriminatory isolation of our Native American communities. However, a change in the nation’s capital can send a strong message.”

“Redskins.” The name of Washington, D.C.’s football team is a racial slur, a racist epithet. The U.S. trademark office agrees; so does the dictionary. But more importantly, Native American people feel it. How important is that to the rest of us? That is the moral question for all of us: are we going to show respect for our nation’s original citizens?

In an insightful column for the Chicago Tribune, Clarence Page compared NBA Commissioner Adam Silver’s decision to ban Clippers owner Donald Sterling “for life” for his private racist comments, with the decision yet to be made by the NFL and Washington’s owner to change a name deeply perceived as a public racist comment. “That’s the question at the heart in the name dispute. Who gets respect,” says Page.

Think about the name. Say it in your head or out loud in a private space. What comes to mind? Try to imagine why Native Americans feel the way they do.

FOR GENERATIONS, Native North Americans and other Indigenous peoples have lived the false belief that a fulfilled relationship with their Creator through Jesus required rejecting their own culture and adopting another, European in origin. In consequence, conventional approaches to mission with Indigenous peoples in North America and around the world have produced relatively dismal outcomes.

The result has subjected Indigenous people to deep-rooted self-doubt at best, self-hatred at worst.

One of the more egregious examples of the “conventional” approach in Canada involved the church-run residential schools. Indigenous children were taken from their families, prevented from speaking their native languages, and subjected to various other forms of abuse.

Isabelle Knockwood, a survivor of church-run residential schools, observed, “I thought about how many of my former schoolmates, like Leona, Hilda, and Maimie, had died premature deaths. I wondered how many were still alive and how they were doing, how well they were coping, and if they were still carrying the burden of the past on their shoulders like I was.”

Given the countless mission efforts over the past four centuries (which in practice were targeted not so much to spiritual transformation as to social and cultural annihilation), we might conclude that Indigenous people must possess a unique spiritual intransigence to the gospel.

Sojourners' online calendar features an image and prayer from various tribes around North and Central America that reflect an Indigenous understanding of God.