AT THE WORLD Christian Gathering of Indigenous People in 1996, our North American Native delegation was unable to find any “Christian” Native powwow music that we could use to dance to as part of our entrance into the auditorium. This was important at the time, as we didn’t feel the liberty to use “non-Christian” powwow music for a distinctly Christian event. A contemporary Christian song by a Caucasian worship leader using some Native words and a good beat was selected.

Except in a handful of cases (believers among the Kiowa, Seminole, Comanche, Dakota, Creek, and Crow tribes, to name some)—and those always in a local tribal context—Native believers were not allowed or encouraged to write new praise or worship music in their own languages utilizing their own tribal instruments, style, and arrangements.

What they were encouraged to do was translate Western-style music, hymns, and songs (for example, “How Great Thou Art,” “Amazing Grace,” “The Old Rugged Cross,” “A Mighty Fortress is Our God”) into their own languages, fully retaining Western cultural musical constructs.

Participation in traditional powwows, with their key features of drumming/singing and dancing, for many Native Christians has been discouraged or forbidden. Long considered a seditious threat to government control and an obstacle to the evangelization of tribal people, there was a long-concerted effort on the part of the U.S. government and missionary organizations and workers to put an end to these practices. Were it solely in the hands of some Native evangelicals to determine what Native ceremonies, rituals, or other cultural practices would be allowed, all would disappear forever, considered by the historic evangelical mission position to be “of the devil,” thus requiring total elimination.

For example, Native pastor and Bible teacher Jim Chosa and co-author Faith Chosa have demonized the Native drum in their book Thy Kingdom Come Thy Will Be Done In Earth, writing, “We also are aware of many cultural elements which are distinctly in contradiction to the Word [Bible] and unredeemable, such as the use of drums as the sole musical instrument for worship of God.”

To demonize the drum is to demonize the songs and the stories that go with it—and the entire genre of traditional Native music.

The Chosas’ dismissal of the Native drum and elevation of Western music (that is, harmony, melody, arrangement, and churchly dependence on the pentatonic scale as reflective of “a heavenly sound”) is a prime example of neocolonialism. Such views emanate from the worldview assumptions of modernity, colonialism, and paternalism that were accepted by earlier missionaries. While these views and attitudes are diminishing in popularity and authority under the weight of the favor contextual efforts are finding, they still prevail in many conservative circles. These attitudes reflect a dualism that neatly divides the human experience into isolated compartments that can be individually analyzed, categorized, and assigned meaning apart from the whole of the experience.

Within that worldview framework, Indigenous music as a “cultural category” has suffered under the weight of the hegemonic bias of a “Western-tuned ear” that cannot hear the beauty of Creator—Jesus—in it. This mindset is absolutely predisposed to reject Native music, dance, and art as uncivilized, pagan, unsophisticated, primitive, base, evil, satanic, and so on.

THE CRUCIALLY IMPORTANT expressions of traditional cultural music and dance have been denied Native followers of Jesus—yet are integral in the development of an “Indigenous hymnody.”

But many Native believers now engaged in contextualization efforts—a relational process of theological and cultural reflection within a community, seeking to incorporate traditional symbols, music, dance, ceremony, and ritual to make faith in Jesus a truly local expression—are experiencing deep meaning as they put on their powwow regalia and dance in a church or Christian gathering or traditional powwow. It helps bring wholeness to their world as both Native and Christian.

In 1995, Mohawk musician Jonathan Maracle wrote a song that was selected to be part of the national March for Jesus soundtrack used all across Canada. The song utilized some Mohawk words, drumming, and style. Maracle had written dozens of songs as a contemporary Christian artist and church worship leader before that time, but all had been Western-style music. The popularity and success of the song opened his eyes to the possibility that Creator could use and bless traditional Native-style music, contrary to what he had been taught by church and ministry leaders in his early Christian experience.

In 1998, Maracle was asked to participate in the World Christian Gathering of Indigenous People in Rapid City, S.D., by leading a session of music for younger participants. It was then that he fully realized the power of Indigenous-style music to convey biblical faith to Indigenous audiences in a way they would enjoy and appreciate—and that would uniquely speak to their “Native heart and soul.” Beyond that, listeners of every ethnic background have found this style of music very moving. More than 130,000 CDs of music written and recorded by Maracle and his band, Broken Walls, have been distributed, and he has performed concerts or led music for Christian events in more than 300 venues. His songs are sung in Native and non-Native churches all across North America.

This Indigenous-style music has been missing in the Native church. It is music that moves the Native soul—unlike a piano, guitar, or synthesizer. Charles H. Kraft notes that the longer a people or group utilizes a majority of foreign forms, the longer Christianity will remain a foreign religion, which I think is particularly true of music. Kraft writes, “When the [Native] Christians think of the Lord as their own, not a foreign Christ; when they do things as unto the Lord meeting the cultural needs around them, worshiping in patterns they understand; when their congregations function in participation in a body, which is structurally Indigenous, then you have an Indigenous church.”

In large part, for a generation of younger Native ministry leaders, the growing contextual movement sprang from the increasing disappointment they felt with the “white character” of the Christianity they had been brought up in. They loved the music, dance, ceremony, and notions of ritual they were beginning to discover in a different reading of the Bible. Moving away from their modernist and culturally Eurocentric-informed view of their own faith journey, they began to long for, dream about, and experiment with new models and forms of expressing their faith as Native men and women.

MARACLE AND MANY other Native Christian musicians compose and perform today in order to serve contemporary purposes and needs, though their music is drawn from and inspired by historical tradition. They come from a background of never or only recently sharing their tribal music as Christians in a Christian setting. They are creating a new genre of music to support the contextual movement and carry the sound of the people along with the message of the gospel of Jesus.

While more conservative Native evangelicals have vigorously opposed the acceptance of these musical innovations and ceremonial adaptations as being what they consider profoundly syncretistic, contextualization efforts also have been viewed with suspicion by more mainline liberals as being “not authentic enough” or disingenuous, being manipulated for “evangelizing the sinner” vs. being embraced as deeply sacramental in a worship context. They have been resisted by the traditionalists because these efforts were viewed as compromising Native religion, or being co-opted by Christian Indians who didn’t really know what they were doing. The traditionalists saw the contextualization efforts as “invading” Indian ways to take them away, or at least to inappropriately borrow them. These tensions still exist.

For the First Nations community of Jesus-followers, there is the huge challenge of how to interpret and incorporate music, dance, and ceremony in light of history, contemporary needs, adaption, and acculturation. This emerging new hymnody is similarly a pastiche of tradition where people are seeking new meanings in old traditions as they attempt to transform a blend of historical/cultural musical constructs, styles, and meanings into a new genre. It is inevitable that something will get lost in the process. Yet this new music has been one of the most attractive and meaningful components of the contextual movement as people experience great personal spiritual enrichment within the context of Native cultural ways. In addition it has served as a dynamic tool of diffusion as thousands of recordings of this style of music have been distributed across the land.

Besides those mentioned earlier, other Native Christian musicians who are writing, recording, and distributing music and have emerged in the past 15 years or so include Robert Soto (Lipan Apache), JoAnne Storm Taylor (Blackfoot), Michael Jacobs (Cherokee), Bill Miller (Mohican), Tom Bee (Lakota), Jan Michael Looking Wolf (Grand Ronde), Terry (Ojibwe/Yaqui) and Darlene Wildman, Jim Miller, Stephen Tindle (Cherokee), and Cheryl Bear (Nadleh Whut’en). This is only a small representation of those who are engaged in contextual music. Their songs are played in musically progressive churches (Native and non-Native) throughout North America.

Today, nearly two decades after the inaugural World Christian Gathering of Indigenous People, when no “Christian” Native powwow of dance music could be found, there is a new and steadily growing ethno-musical library of Native-style worship music being written, recorded, and distributed by Native artists. All societies have their own unique music, and now an Indigenous hymnody has begun to emerge out of the contextualization movement in North America.

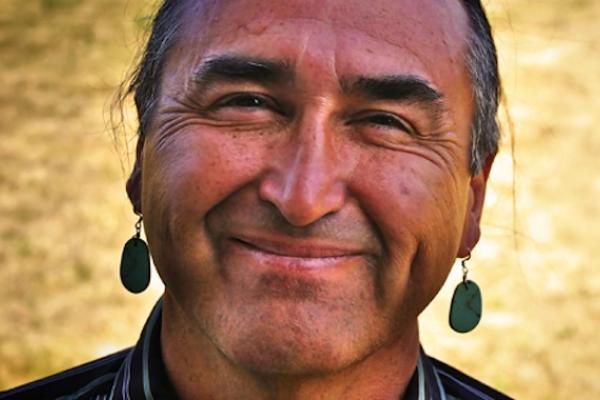

This article is excerpted and adapted from Rescuing the Gospel from the Cowboys, by Richard Twiss. Copyright (c) 2015 by Richard Twiss. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515, USA. www.ivpress.com

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!