Native American

The Native American narrative remains largely unknown in U.S. majority culture. It is glaringly absent in most school curriculums, and remains unheard in modern dominant politics. One crucial stream of Native culture I’ve recently come to learn about is the destructive legacy of Christian-run Indian boarding schools.

What began with genuinely good intentions (in those days, “European” norms were viewed as superior, “sameness” seemed like a good idea, and the threat of legitimate genocide lingered over tribes) rapidly deteriorated, with Christian boarding schools becoming institutions of forced assimilation and abuse.

Beginning in the 1800s and lasting into the 20th century, Native children were forcibly removed from their families and sent to live in boarding schools. Finding the task of “civilizing” Native adults beyond its ability, the federal government delegated the task of “normalization” to churches, which could educate, or, inculcate, children from a young age.

The Baby Veronica case, named for the girl at the center of a contentious child custody dispute, has stirred powerful emotional responses from many groups, including some Christian evangelicals.

Motivated by their faith in God and a distrust of federal Indian policies, a few evangelical organizations are campaigning to abolish the federal Indian Child Welfare Act at the heart of the dispute.

Congress enacted the law in 1978 to address the abuses that separated Indian children from their families through adoption or foster care. The law gives related tribes a preference in custody proceedings involving Indian children.

As a young Iroquois boy living on the Onondaga Nation, Hickory Edwards paddled, swam, fished and caught crabs in the creek close to his parents’ house.

To celebrate his love of the water, Edwards is leading a group of about 200 people paddling canoes and kayaks down the Hudson River from Albany to New York City as part of the Two Row Wampum Renewal Campaign.

“I feel really close to the water,” Edwards said. “It’s life-giving, and to be so close to water is to be close to nature.”

The nine-day journey, from July 28 to Aug. 9, is part of a yearlong educational program marking the 400th anniversary of the 1613 agreement between the Haudenosaunee, or the Iroquois, and the Dutch settlers.

A Methodist pastor of a suburban Oklahama City church is suing the state, claiming its license plate image of a Native American shooting an arrow into the sky violates his religious liberty.

Last week, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver ruled his suit can proceed.

The pastor, Keith Cressman of St. Mark’s United Methodist Church in Bethany, Okla., contends the image of the Native American compels him to be a “mobile billboard” for a pagan religion.

"The antidote to feel-good history is not feel-bad history but honest and inclusive history." – James Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me, 92.

It’s becoming increasingly difficult for Americans to celebrate Thanksgiving. This Thanksgiving, as we take turns around the dinner table sharing why we are thankful, a sense of awkwardness settles in. The awkwardness is not only due to the “forced family fun” of having to quickly think of something profound to be thankful for. (Oh, the pressure!) The growing awkwardness surrounding Thanksgiving stems from the fact that we know that at the table with us are the shadows of victims waiting to be heard.

Humans have an unfortunate characteristic – we don’t want to hear the voice of our victims. We don’t want to see the pain we’ve caused, so we silence the voice of our victims. The anthropologist Rene Girard calls this silencing myth. Myth comes from the Greek worth mythos. The root word, my, means “to close” or “to keep secret.” The American ritual of Thanksgiving has been based on a myth that closes the mouths of Native Americans and keeps their suffering a secret.

SYRACUSE, N.Y. — Sister Kateri Mitchell was born and raised on the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation along the St. Lawrence River. She grew up hearing stories about Kateri Tekakwitha, the 17th-century Mohawk woman who will be declared a saint in the Roman Catholic Church on Sunday.

She has long admired Tekakwitha for her steadfast faith and her ability to bridge Native American spirituality with Catholic traditions. In 1961, Mitchell joined the Sisters of St. Anne, and since 1998 she has served as executive director of the Tekakwitha Conference in Great Falls, Mont., a group that has spread Tekakwitha’s story and prayed for her canonization since 1939.

“We’ve been waiting a long time for this,” she said of the canonization at the Vatican. “It’s a great validation.”

MOHAWK VALLEY, New York — Twelve-year-old Jake Finkbonner leaned over and ran his hand through a pool of water from a natural spring at the National Shrine of Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha, in Fonda, N.Y.. With that simple gesture, on a recent July weekend, the boy connected literally to the story of the 17th-century Native American woman who the Roman Catholic Church will elevate to sainthood on Oct. 21.

Jake had already connected to her story in what he believes is a miraculous way. The boy's inexplicable recovery from a flesh-eating illness in 2006 is attributed to prayers to Kateri (pronounced Gad-a-lee in Mohawk) on his behalf.

Jake, who is of Lummi descent, said he's gotten used to the attention he draws when people learn he's at the center of the miracle that led the Vatican to decide to proclaim Kateri a saint — a step that will make her one of the church's holy role models, and the first Native American to be canonized.

He likes to read and play basketball, and he loves video games. He and his 10-year-old sister, Miranda, are also training to become altar servers.

"I feel a great amount of gratitude and thanks to her," Jake said of Kateri.

We often hear that there’s a “war on religion,” that certain expressions of Christianity are under attack by secularists seeking a new age of post-God. And while things may or may not be easy for Christians, our rituals are not prohibited by law, like some of our Native American neighbors.

Until recently, it was illegal for Native Americans to acquire bald eagle feathers and parts – relics used for a variety of tribal rituals and ceremonies – by any means other than family or the National Eagle Repository in Denver.

? U.S. troops on the front line believe that the war will go on for another 10 years after they leave.

? An audit shows that the surge of U.S. civilian advisers has cost nearly $2 billion.

? The U.S. mission in Afghanistan has suspended the transfer of detainees to several Afghan jails, following torture allegations.

Life Stories

Alison Owings interviewed members of 16 tribal nations for the oral history Indian Voices: Listening to Native Americans, capturing intimate, engaging perspectives from long-overlooked communities. An inspiring antidote to the ignorance many non-Indigenous people may unwittingly hold about contemporary Native American lives. Rutgers University Press

Broadcaster Tavis Smiley and Princeton professor Cornel West just wrapped up their 18-city "Poverty Tour." The aim of their trip, which traversed through Wisconsin, Detroit, Washington, D.C., and the Deep South was to "highlight the plight of the poor people of all races, colors, and creeds so they will not be forgotten, ignored, or rendered invisible." Although the trip has been met with a fair amount of criticism, the issue of poverty's invisibility in American media and politics is unmistakable. The community organizations working tirelessly to help America's poor deserve a great deal more attention than what is being given.

The main attack against the "Poverty Tour" is Smiley and West's criticism of Obama's weak efforts to tackle poverty. For me though, what I would have liked to see more is the collection of stories and experiences from the people West and Smiley met along their trip. The act of collective storytelling in and of itself can be an act of resistance.

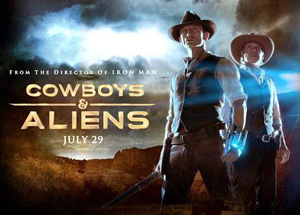

Americans have a hard time knowing how to respond to the sins of our colonial past. Except for a few extremists, most people know on a gut level that the extermination of the Native Americans was a bad thing. Not that most would ever verbalize it, or offer reparations, or ask for forgiveness, or admit to current neocolonial actions, or give up stereotyped assumptions -- they just know it was wrong and don't know how to respond. The Western American way doesn't allow the past to be mourned or apologies to be made. Instead we make alien invasion movies.

Americans have a hard time knowing how to respond to the sins of our colonial past. Except for a few extremists, most people know on a gut level that the extermination of the Native Americans was a bad thing. Not that most would ever verbalize it, or offer reparations, or ask for forgiveness, or admit to current neocolonial actions, or give up stereotyped assumptions -- they just know it was wrong and don't know how to respond. The Western American way doesn't allow the past to be mourned or apologies to be made. Instead we make alien invasion movies.

During my travels connecting with communities as part of an extended listening tour for Jesus Died for This?: A Satirist's Search for the Risen Christ, I hung about a bit with Mark Van Steenwyk, co-founder of Missio Dei, an anabaptist intentional community in Minneapolis, Minnesota. I was intrigued to learn about their work with the Christian Peacemakers Team (CPT), so I decided to shoot him an email to see what's in store for them during spring 2011.

I've been fascinated watching an earlier blog hunker down into a strong debate about Israel and the Palestinians (February 22, "

"Yes, Muslims have the constitutional right to build a mosque near Ground Zero.

[Editor's Note: This week we will have a series of reviews on films with a focus on immigration. Check back each day for a new film review, and visit www.faithandimmigration.org for more information]