Race

American Promise spans 13 years as Joe Brewster and Michèle Stephenson, middle-class African-American parents in Brooklyn, N.Y., turn their cameras on their son, Idris, and his best friend, Seun, who make their way through one of the most prestigious private schools in the country. Chronicling the boys’ divergent paths from kindergarten through high school graduation at Manhattan’s Dalton School, the documentary presents complicated truths about America’s struggle to come of age on issues of race, class, and opportunity. American Promise is an Official Selection of the 2013 Sundance Film Festival.

The most controversial sentence I ever wrote, considering the response to it, was not about abortion, marriage equality, the wars in Vietnam or Iraq, elections, or anything to do with national or church politics. It was a statement about the founding of the United States of America. Here’s the sentence:

"The United States of America was established as a white society, founded upon the near genocide of another race and then the enslavement of yet another."

The comments were overwhelming, with many calling the statement outrageous and some calling it courageous. But it was neither. The sentence was simply a historical statement of the facts. It was the first sentence of a Sojourners magazine cover article, published 26 years ago titled “America’s Original Sin: The Legacy of White Racism.”

An extraordinary new film called 12 Years a Slave has just come out, and Sojourners hosted the premiere for the faith community on Oct. 9 in Washington, D.C. Rev. Otis Moss III was on the panel afterward that reflected on the film. Dr. Moss is not only a dynamic pastor and preacher in Chicago, but he is also a teacher of cinematography who put this compelling story about Solomon Northup — a freeman from New York, who was kidnapped and sold into slavery — into the historical context of all the American films ever done on slavery. 12 Years is the most accurate and best produced drama of slavery ever done, says Moss.

In her New York Times review, “ The Blood and Tears, Not the Magnolias,” Manohla Dargis says, 12 Years a Slave “isn’t the first movie about slavery in the United States — but it may be the one that finally makes it impossible for American cinema to continue to sell the ugly lies it’s been hawking for more than a century.” Instead of the Hollywood portrayal of beautiful plantations, benevolent masters, and simple happy slaves, it shows the utterly brutal violence of a systematic attempt to dehumanize an entire race of people — for economic greed. It reveals how morally outrageous the slave system was, and it is very hard to watch.

When we consider the typical church worship service in the United States, we discover certain trends. Lament and stories of suffering are conspicuously absent. In Hurting with God, Glenn Pemberton notes that laments constitute 40 percent of the Psalms, but in the hymnal for the Churches of Christ, laments make up 13 percent, the Presbyterian hymnal 19 percent, and the Baptist hymnal 13 percent.

Christian Copyright Licensing International (CCLI) licenses local churches for the use of contemporary worship songs. CCLI tracks the songs that are employed by local churches, and its list of the top 100 worship songs as of August 2012 reveals that only five of the songs would qualify as a lament. Most of the songs reflect themes of celebratory praise: “Here I Am to Worship,” “Happy Day,” “Indescribable,” “Friend of God,” “Glorious Day,” “Marvelous Light,” and “Victory in Jesus.”

How we worship reveals what we prioritize. The American church avoids lament. Consequently the underlying narrative of suffering that requires lament is lost in lieu of a triumphalistic, victorious narrative. We forget the necessity of lament over suffering and pain. Absence doesn’t make the heart grow fonder. Absence makes the heart forget. The absence of lament in the liturgy of the American church results in the loss of memory.

Are we waiting for another Dr. King? As I collect my thoughts to write these words, I’m mindful that I don’t honestly know what discrimination is. I have never (consciously) experienced discrimination because of my race, the color of my skin, or where I come from. I have never had to say, like Solomon Northup, “I don’t want to hear any more noise.” In the film, 12 Years a Slave, Solomon refers to the cry of those being beaten and separated from their children. I speak here with a profound sense of respect and fear. Who am I, or maybe even you who read, to speak about a tragedy and a pain that we have never experienced? I only speak out of a sense of duty and a calling from God.

Dr. King wrote, “So many of our forebears used to sing about freedom. And they dreamed of the day that they would be able to get out of the bosom of slavery, the long night of injustice … but so many died without having the dream fulfilled.” (A Knock at Midnight, p.194)

To this day, millions of African Americans in our country still dream about getting out of the bosom of slavery. Slavery today is masked behind the social, financial, political, and even religious systems that deny the dignity and full integration into these systems to people of color. Solomon Northup cries out in the film saying, “I don’t want to survive, I want to live.” The struggle of African Americans is a struggle to live. So far, they have only survived.

Crickets chirping, a branch creaks, and a black body swings on a tree whose roots grow deep into a shared story of our American past. These are images that are floating in my mind, after watching a pre-screening of12 Years a Slave. This film was a terribly beautiful depiction of the antebellum south and the atrocity known as slavery. Its honesty was riveting, as the film portrays characters in ways never captured before on the big screen. They were characters such as Mistress Shaw (played by Alfre Woodard), the black wife of a slave master who is adored by her husband and treated as a white woman. In a panel discussion, Lisa Sharon Harper of Sojourners asked Woodard, about this character. And she responded that in the South, there were all kinds of arrangements between whites and blacks. Her character Mistress Shaw learned how to survive. I was so refreshed that 12 Years a Slave, was a new depiction of slavery instead of a rehashing of Roots orAmistad.

The panel also consisted of a plethora well-informed faith leaders. One of the panelists, Jim Wallis, while discussing the aspects of faith profoundly said, “Enslaved Africans saved Christ from the Christians.” I was immediately struck by his words as they reminded me of how I became a Christian.

Strange but beautiful things happen when we begin to identify with people who are culturally different. A few years ago, I became friends with Peter, a guy at my church who also happened to be an undocumented immigrant. One day over lunch, he shared that his mother (whom he hadn’t seen in 15+ years) had recently been diagnosed with a terminal disease. He desperately wanted to visit her, but due to his immigration status, he knew that if he left the U.S. he wouldn’t be allowed to return. Given his obligations to his family in the U.S., Peter made the heart-breaking decision to not to visit his dying mom.

As a U.S. citizen, I hadn’t personally experienced the trials of being undocumented or felt the frustration of geographic immobility while a loved one approached death in a far off land. But throughout my friendship with Peter — getting to know his family in the U.S., listening to him share about the harrowing challenges he experienced on a daily basis, and seeing photographs of his life and family in his home country — I got a glimpse of the world from his perspective. In many ways, Peter’s life was marked by sorrow and loss – and that was more evident than ever during our lunch conversation that day.

I pre-screened 12 Years a Slave the same weekend I saw Gravity. The two films couldn’t be more different, although they do have some fascinating (if not immediately obvious) commonalities.

As for commonalities, they’re both powerful and both deserve to be seen. Both are about people trying to get home — one, in a harrowing adventure that takes several hours, the other in an agonizing 12-year struggle. The protagonists of both movies demonstrate heroic resilience and courage. One struggles with physical weightlessness, the other with a kind of social or political weightlessness.

Although Gravity impressed and fascinated me, 12 Years a Slave affected me and shook me up. Now, several days later, scenes from the film keep sneaking up on me and replaying in my imagination — three in particular.

The ethos of slavery still runs deep in our national consciousness. Alfre Woodard, a supporting actress in the upcoming movie 12 Years a Slave, hopes that point is taken by all who see it.

“Whenever there is repression, it takes toll on everyone; especially a physical and psychic, stunting pain on the abuser,” Woodard said at a panel following a pre-screening of the movie hosted by Sojourners last week. “My hope, expectation is that audiences will start to think about slavery in a new way. That they’ll come away with some small perspective to understand each other better.”

The panel gathered to begin the conversation about residual impacts of slavery on the United States. Woodard started the discussion with a description of what it was like to be set and involved with a film that revolves around such a difficult emotional topic.

[view:Media=block_1]

I watched 12 Years a Slave today. The film is based on Solomon Northup’s autobiography by that name. Northrup was a free black man living in Saratoga, N.Y. He was lured away from his home to Washington, D. C., on the promise of lucrative work and was kidnapped, transported to Louisiana, and sold into slavery. He was rescued 12 years later.

Some of the questions and issues that the movie raises are: What right do people have to own others? Do money and might make right? Unjust laws — such as slave laws — exist. It just goes to show that something can be legal, yet morally wrong. Still, laws come and go. We must not confuse laws with rights, which are universal and enduring truths that do not change. What is true and right and good is always so. So, too, that which is evil is always evil. Even if unjust laws are overturned and abolished, evil can still return in other guises.

I asked myself as I watched the movie, “Could it happen again?” Some of us may think, “Surely, something like this could never happen in our day.” And yet, people are abducted and sold into various forms of slavery here and abroad on a daily basis. Granted — people are not publicly bought and sold on the slave block in America today because of skin color; however, people are enslaved based on race and class divisions.

Since the production of The Birth of a Nation, Hollywood has lived with the mythic world imagined by artists who view the lives of people of color as footnotes and props. From Gone With The Wind to Django Unchained, the most difficult type of film for Hollywood to get right is the antebellum story of people of color.

Django, for example used the archetypes designed by Hollywood — “Mammy, Coon, Tom, Buck, and Mulatto,” to quote film historian, Donald Bogle — and exploit them in order to create a hyper-exploitation Western fantasy, with slavery as the backdrop. The film is a remix and critique of exploitation clichés, not a historical drama seeking to illuminate our consciousness. Django is a form of visual entertainment where enlightenment might happen through a close reading of the film. All the archetypes remain in place. Nothing is exploded or re-imagined, only remixed to serve the present age.

Steve McQueen’s 12 Years A Slave, on the other hand, sits within and outside the Hollywood fantasy of antebellum life. I say it sits within, because the archetypes forged by the celluloid bigotry of D.W. Griffith are present. But, in the hands of the gifted auteur, Steve McQueen, they are obliterated and re-imagined as complex people caught in a system of evil constructed by the immorality of markets, betrothed to mythical, biological, white supremacy.

In my lifetime I’ve driven on three roadways named after Martin Luther King, Jr. One was a street, another a boulevard, and the third a highway. And whether by cosmic irony or human design, each of these roadways passes through communities of significant poverty and color, namely black. Around these roadways are boarded up storefronts, crack and heroin dens (think The Wire), condemned row houses, and inevitably, always – public schools.

From 2001 to 2006 I left the safety of the pulpit to teach in the schools of Baltimore and Washington, D.C., pursuing a call to care for the proverbial least of these (it’s always pained me to think how I might feel to be called this, as in hey, you least of these, can I help you with anything? – but that’s a reflection for another time). I left also the safety of a suburban megachurch, where all you needed to do to understand the socioeconomic standing of its members was to walk through the parking lot, and the familiar cultural context of my Korean-American upbringing.

This article, however, is not about me. It’s about beautiful, creative, energetic, and intelligent children — kids who, as the least of these, are too often treated as such. There is no limit to blame: from the mother who comes to school drunk, a prostitute, publically shaming her son (who loves her nonetheless and gets beaten by the other boys defending her honor); to the worn-out teacher who drags a “difficult” child into the bathroom, bruising her arms and threatening her with verbal vitriol and rage; to the administration that promotes student after student, knowing they are years behind, but too old to remain; to the system that maintains, protects, and worships a biblical truism, that for to all those who have, more will be given, and they will have an abundance; but from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away (Mt.25:29).

I remember the first time I ever got straight A’s. It was also the last time.

I was in Mrs. Becker’s 4th grade class at John Story Jenks School in Philadelphia. I was always good at reading, I LOVED science projects, and art class was fun — but math? Ugh. Math was my nemesis. In 4thgrade the times tables felt as insurmountable as that dang rope everybody else could whiz up and down in gym class. I just couldn’t figure it out. In fact, to this day, I haven’t figured the rope.

So, my father became my times tables drill sergeant and resorted to straight memorization tactics, making me write each one 10 times. Then he sat across from me at the dining room table and drilled me on the times tables until I said them in my sleep. It was brutal … and oddly, one of the fondest memories of my elementary school years. Not only did I master multiplication, but I also learned something much more important. When my report card came back that quarter with straight A’s, I learned that I could learn!

I GREW UP in rural Mississippi, a black girl who lived “out in the booneys,” fairly isolated from peers outside school. My God-fearing parents brought me up in an African Methodist Episcopal church that stood just beyond the edge of the woods. At the right age, I waded into a muddy watering hole, only recently vacated by the cows who drank there, and got dunked by the preacher and welcomed into the church and the kingdom of God.

That was my baptism, but I wouldn’t call it a conversion experience. I felt very innocent then, and would until I left home for college in Massachusetts. There I got my first taste of diversity. Most of my classmates didn’t believe as I did. Most of my African-American friends felt as if my faith was some kind of relic from our slave heritage, a white-supremacist trick that I had bought into.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King immortalized many phrases still used in the contemporary American lexicon. But it was on Dec. 17, 1963 in a talk at Western Michigan University when he noted that the “most segregated hour in this nation” is 11 a.m. on Sunday.

Though many of King’s other famous quotes come from scripted speeches, the comment above actually was from part of a question-and-answer session with students and faculty about racial integration. He was asked if he believed that true racial integration must be spearheaded by the Christian churches, rather than in workplaces or on college campuses.

Suffice it to say that Dr. King begged to differ, and sadly, his words spoken 50 years ago ring eerily prophetic as we scan the halls of most of our churches. What he claimed then is still, today, a stark reality. He went on in his response:

“I’m sure that if the church had taken a stronger stand all along, we wouldn’t have many of the problems that we have. The first way that the church can repent, the first way that it can move out into the arena of social reform is to remove the yoke of segregation from its own body.”

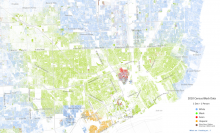

But how? About the same time King made these keen observations, white people were leaving the inner cities by the millions, establishing more homogenous suburbs on the far boundaries of town. So-called “white flight” took hold, creating entirely new municipalities, while decaying urban centers were hollowed out, left only with an aging infrastructure and those who had no choice but to endure being left to fend for themselves.

As such, our churches were, in some ways, byproducts of the communities in which they found themselves.

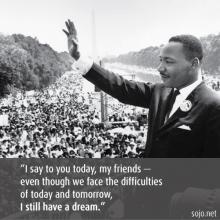

Yesterday was the 50th anniversary of a day that changed America, changed the world, and changed my life forever. I was fourteen years old on Aug. 28, 1963, in my very white neighborhood, school, church, and world. But I was watching. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., became a founding father of this nation on that day, so clearly articulating how this union could become more perfect.

He didn’t say, “I have a complaint.” Instead, he proclaimed (and a proclamation it was in the prophetic biblical tradition), “I have a dream.” There was much to complain about for black Americans, and there is much to complain about today for many in this nation. But King taught us that day our complaints or critiques, or even our dissent will never be the foundation of social movements that change the world — but dreams always will. Just saying what is wrong will never be enough the change the world. You have to lift up a vision of what is right.

The dream was more than the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, which both followed in the years after the history-changing 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It finally was about King’s vision for “the beloved community,” drawn right from the heart of his Christian faith and a spiritual foundation for the ancient idea of the common good, which we today need so deeply to restore.

WASHINGTON — Fifty years to the day after Martin Luther King, Jr., knocked on the nation’s conscience with his dream, religious leaders gathered in a historic church to remind the nation that he was fueled by faith.

Later, in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial where King thundered about America’s unmet promises, King’s children joined the likes of President Barack Obama and Oprah Winfrey to rekindle what Obama called a “coalition of conscience.”

At Shiloh Baptist Church, where King preached three years before his 1963 “I Have A Dream” speech, Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Sikh clergy summoned King’s prophetic spirit to help reignite the religious fires of the civil rights movement.

King’s daughter, the Rev. Bernice A. King, said at the service that her father was a freedom fighter and a civil rights leader, but his essence was something else.

“He was a pastor,” said King, who was 5 when her father electrified the nation in front of the Lincoln Memorial. “He was a prophet. He was a faith leader.”

Editor's Note: The following is a transcript of President Barack Obama's speech from the Lincoln Memorial on the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington.

We rightly and best remember Dr. King’s soaring oratory that day, how he gave mighty voice to the quiet hopes of millions; how he offered a salvation path for oppressed and oppressors alike. His words belong to the ages, possessing a power and prophecy unmatched in our time.

But we would do well to recall that day itself also belonged to those ordinary people whose names never appeared in the history books, never got on TV. Many had gone to segregated schools and sat at segregated lunch counters. They lived in towns where they couldn’t vote and cities where their votes didn’t matter. They were couples in love who couldn’t marry, soldiers who fought for freedom abroad that they found denied to them at home. They had seen loved ones beaten, and children fire-hosed, and they had every reason to lash out in anger, or resign themselves to a bitter fate.

The upcoming March on Washington has been on my mind as I reflect upon this week’s Gospel reading from Luke about a banquet. I personally love banquets. You get to adorn yourself with the finest trappings, dance the night away, and if the food is good, that is an added plus! But what I find most frustrating? Knowing a banquet is occurring, and I have not been invited. “Did I do something wrong? Do I not meet a certain standard? Who did get invited?” My wondering is filled with emotion.

What if America was a banquet, and at this banquet the servings were fair wages, just trials, civil rights and liberties, but offered by invitation only? According to those who “March(ed) on Washington,” this was exactly the case. Blacks deserved the same fair treatment as whites, and they were protesting to bring about the necessary changes. Perhaps if everyone took heed of Jesus’ instructions on banquet etiquette, things would be different and better.

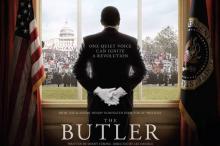

As people stepped on our toes and stood anxiously in front of us, waiting to exit the crowded theater, three of us sat weeping at the close of Lee Daniels’ The Butler. Even now, as I recall that moment, it brings tears to my eyes.

How do I describe the movie? Utterly intense. Remarkable. Heartbreaking. Inspiring. A genius capturing of the complexities of the Civil Rights Movement, of the history of race in America in the 20th and early 21st centuries, of presidential decision making, and of family.

I sat next to my colleague, Lisa Sharon Harper, who sobbed at the violence, tragedy, and passionate courage displayed on screen. It was a challenge. To be a white woman sitting next to an African-American woman as she wept over the suffering of her people — often at the hands of my people. It was neither her nor I who had perpetrated these specific acts, but we are certainly still caught in the tangled web of systemic racism and the histories that our ancestors have wrought us.

Even as we had waited in the theater prior to the movie's start, we spoke of serious subjects. She shared some of her lineage and the challenges of legal records that simply do not exist when ancestors are slaves or perhaps a Cherokee Indian who escaped the Trail of Tears in Kentucky and suddenly appears on the U.S. Census in 1850 as an adult. We spoke of her leadership in the church, and I encouraged her to continue speaking even though she is one of the lone women who graces the stages in front of national audiences. I told her, "You must do this so that other women who come after you can do this. You must do this for women right now. You must do this so that I can do this." We bonded over being women in ministry.

And then the separation came. I do not know Lisa's shoes — the road that she walks due to the color of her skin. I see her in all of her glory — passion, intelligence, creativity — and not in all of her blackness. Our world sees her with racial eyes.

This year marks the 150th anniversary of both the issuing of Emancipation Proclamation and the battle of Gettysburg. This month marks the 50th anniversary of the historic March on Washington and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. All three moments marked major turning points in the fundamental American struggle to actualize the divine dream of life, liberty, and equality for all. That dream has been especially powerful through the struggle for African-American freedom.

From a biblical perspective, American slavery and Jim Crow segregation not only subjugated the body. For about 300 years, from Virginia’s first race-based slave laws in the 1660s to the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, the legal binding of black hands, feet, and mouths also bound spirits and souls. Both slavery and Jim Crow laws denied the dignity of human beings made in the image of God and forbade them from obeying God’s command to exercise Genesis 1:28 “dominion” — in today’s terms, human agency.

So, the Emancipation Proclamation and passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were cause for jubilee worship in black churches and among other abolitionists. Likewise when the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965, churches across the nation erupted again in worshipful jubilee.

Now, nearly 50 years after the second American jubilee, African Americans are being stripped of dignity and constitutionally protected freedoms like we have not seen since Jim Crow.