Peace

IN "SILENCE FOR GAZA,” Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish captures the contradictions of the coastal enclave, describing it alternately as “ugly, impoverished, miserable,” and “the most beautiful, the purest and richest among us.” Darwish’s antonyms evoke Gaza’s crushing conditions and resilient residents, exemplars of sumud, an Arabic word roughly translated as “steadfast perseverance”—a fundamental form of Palestinian resistance. Darwish’s poem also states that Gaza “did not believe that it was material for media. It did not prepare for cameras and did not put smiling paste on its face.” And yet every person, every story, every image of Gaza illustrates this persistent paradox of a land at once ugly and beautiful.

“I DON’T KNOW why they targeted us. No rockets were fired from our neighborhood,” says citrus farmer Yusuf Jilal Arafat, whose 5-year-old daughter Runan was killed when Israeli warplanes bombed their home. Arafat’s wife, four months pregnant, and their 8-year-old son were found alive in the rubble. His surviving children now suffer from frequent panic attacks at night. Many of Arafat’s trees were destroyed by the bombs, and the ground is covered with oranges now in various stages of decay. Rumors of contamination by Israeli weapons may hurt the sales of his crop, but he will still harvest. The family is living with Arafat’s father-in-law until they can rebuild.

Rebuilding under Israeli import restrictions is no simple task, so salvaging existing materials remains a vital practice—albeit risky, according to structural engineers. But ingenuity-by-necessity is constantly on display in Gaza, whether it’s recovering crushed stone from beneath ruined highways, straightening steel rebar from bombed-out buildings, or pulverizing concrete for reuse in new (but weaker) blocks.

IN HER JEWISH school in Montreal, Ronit Avni learned the tragic history of her people. Her Canadian mother and Israeli father had met in the ’60s when her mother was living in Israel and working as a folk singer, often performing for Israeli troops. Her older sister was born in Tel Aviv, but the family settled back in Montreal in the mid-’70s before Ronit was born.

Not strictly religious but committed to the values of Judaism, Ronit couldn’t help but ask probing questions as she listened to the stories of the birth of the modern state of Israel in 1948. Am I hearing the whole story? How do Palestinian perspectives differ from what my educators and community leaders are teaching? How can we transform this situation from a zero-sum equation to one that respects the dignity and freedom of all?

Years later, having graduated with honors from Vassar College with a degree in political science after studying theater at a conservatory in Montreal, Ronit trained human rights advocates worldwide to produce videos as tools for public education and grassroots mobilizing.

By the time I met Ronit a few years ago, she had narrowed her worldwide focus to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, where her heart was most deeply drawn. She is the founder and executive director of Just Vision, an organization dedicated to increasing media coverage and support for Palestinian and Israeli efforts to end the occupation and conflict without weapons of violence.

During the last several years, my engagement in the Holy Land has been significantly shaped by Ronit. Her film Encounter Point, about Israelis and Palestinians who have lost family members, land, or liberty to the conflict yet choose forgiveness and reconciliation rather than revenge, gave me hope that peace can emerge from pain.

THE FONDEST memories I have of Kathy Kelly are of her singing. It’s safe to say that her three nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize were not for her voice, which is sometimes sweet but often a touch out of key. At times I’ve imagined her feeling briefly self-conscious about this, but that passes. The song remains, and I am again reminded of just how deeply this woman can move me.

In spring 1999, in a small banquet room at Georgetown University, I first heard Kelly sing and speak about the suffering in Iraq. A crowd of about 200 people had gathered to hear about her work. She had been to Iraq dozens of times to put a human face on the conflict there and to defy the drastic financial and trade embargo that the U.N. Security Council had imposed shortly after Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

She briefly went over the statistics—the deep poverty, the lack of medicines, the estimated half-million children who had died, many due to the U.N. sanctions, enforced in part by a U.S.-led blockade—but she quickly moved on. Statistics weren’t her strength.

Instead she spoke from the heart. Kelly talked about the ordinary Iraqis she had met: the worn women who served her tea and biscuits they could barely afford, the countless kids in threadbare hand-me-downs who ran after her merrily in the street, the tired doctors who broke down crying as they remembered all the children they had lost, the stone-faced parents who accepted her condolences because they didn’t know what else to do.

She also told the story of Zayna, a 7-month-old baby girl who died of malnutrition shortly after Kelly visited her in the hospital.

WHEN I WAS growing up in the western suburbs of Chicago, I felt so far outside of the inner circle of cool kids that I didn’t even know where the circle was. So you can imagine my delight when I got an invitation to David’s birthday party. David was in the outer part of the inner circle, which meant I was heading in the right direction.

A couple days before the party, my mom took a closer look at the invitation and noticed that it said David’s parents would be making hot dogs for lunch. As she wasn’t sure whether the hot dogs were pork or beef, and as we were Muslims who don’t eat pork, she informed me that she’d be giving me all-beef franks to take from home with a note to David’s mom asking her to fry them up in a separate pan.

Of course, this horrified me, the kind of horror that only a kid caught up in the jungle of grade school coolness competition can feel. I remember standing in the living room, staring at my mom, and thinking to myself: “First, you named me Eboo.”

The day of the party rolled around and, dutiful Indian-Muslim child that I was, I accepted the little plastic baggie with two beef hot dogs that my mom handed me, allowed her to put me in nice slacks and a collared shirt, and went off to the party. When lunchtime came, I snuck into the kitchen to make my request of David’s parents. Imagine my surprise when I noticed another kid in the kitchen. He wore a collared shirt and nice slacks and also held a plastic baggie with two hot dogs.

In the fourth chapter of Genesis, after the proverbial “fall” of humanity, two brothers stand in a field. Cain is a farmer — Abel, a herdsman. Both bring offerings from their labor to God, but Abel brings his first fruits, so God looks on Abel’s offering with delight. In a jealous rage Cain rises up against Abel and kills him. This is the first recorded murder in the Bible.

I will never forget walking onto the National Mall early on the morning of April 11, 2013. As I approached a mass of people and television cameras between the Washington Monument and the Capitol Building I was overcome by the sight of more than 3,300 crosses and other religious symbols rising from the heart of our capital city. They represented the graves of all the people who have died by gunfire since the December 14, 2012 shooting massacre at Newtown, Conn. It was profound. It was overwhelming.

Paul Rand quoted scripture and used biblical principles as he made his case against excessive American engagement overseas. He quoted Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount: “Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God.” Paul also stressed the military should be used sparingly. Politico reports:

“I can recall no utterance of Jesus in favor of war or any acts of aggression,” Paul said at a kickoff luncheon for the Faith and Freedom Coalition conference. “In fact, his message to his disciples was one of non-resistance.”

Star Trek: Into Darkness is a fascinating and complicated story that is well worth watching. Instead of providing a summary, I want to explore three related aspects of the movie: sacrifice, blood, and hope for a more peaceful future.

Live Long and Prosper – The Sacrificial Formula

In a reference to my favorite Star Trek movie, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, the current movie’s Spock (Zachary Quinto) restates the sacrificial formula: “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the one.” This formula has generally been used throughout human history to justify sacrificing someone else. As René Girard points out, from ancient human groups to modern societies, whenever conflicts arise the natural way to find reconciliation is to unite against a common enemy.

Of course, there’s a lot of this going on throughout the Star Trek franchise. One conversation in Into Darkness explicitly points this out when Kirk (Chris Pine) unites with his enemy Khan (Benedict Cumberbatch), and explains it to Spock:

Kirk: The enemy of my enemy is my friend.

Spock: An Arabic proverb attributed to a prince who was betrayed and decapitated by his own subjects.

Kirk: Well, it’s still a hell of a quote.

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY in Lynchburg, Va., was founded by televangelist Jerry Falwell. Its publications carry the slogan “Training Champions for Christ since 1971.” Some of those champions are now being trained to pilot armed drones, and others to pilot more traditional aircraft, in U.S. wars. For Christ.

Liberty bills itself as “one of America’s top military-friendly schools.” It trains chaplains for the various branches of the military. And it trains pilots in its School of Aeronautics (SOA)—pilots who go up in planes and drone pilots who sit behind desks wearing pilot suits. The SOA, with more than 600 students, is not seen on campus, as it has recently moved to a building adjacent to Lynchburg Regional Airport.

Liberty’s campus looks new and attractive, large enough for some 12,000 students, swarming with blue campus buses, and heavy on sports facilities for the Liberty Flames. A campus bookstore prominently displays Resilient Warriors, a book by Associate Vice President for Military Outreach Maj. Gen. (Ret.) Robert F. Dees. There’s new construction everywhere you look: a $50 million library, a baseball stadium, new dorms, a tiny year-round artificial ski slope on the top of a hill. In fact, Liberty is sitting on more than $1 billion in net assets.

The major source of Liberty’s money is online education. There are some 60,000 Liberty students you don’t see on campus, because they study via the internet. They also make Liberty the largest university in Virginia, the fourth largest online university anywhere, and the largest Christian university in the world.

Jesus says some stuff in the inaugural speech of his ministry that really upsets the status quo of both the religious and non-religious. In essence, he says, "If you are to follow me as King of this newly inaugurated Kingdom of God, you will need to start loving your enemies as much as yourself. You will need to start getting creative in how you deal with your oppressors in order to choose the way of love and reconciliation rather than the way of revenge and contempt. In fact, when you live as peacemakers, you best reflect what it looks like to be children of God. Those of you that choose this way of life will be blessed."

A few years later — after Jesus has been announcing the good news of the Kingdom through both word and deed — he looks over Jerusalem and begins to weep. Here is the people and the city that is to symbolize right relationship with God and humanity. It is to be a place of shalom where salvation flows through all aspects of life. It is to be the city of peace. Instead, Jesus stands on the Mount of Olives overlooking the city and laments, "If you, even you, had only recognized on this day the things that make for peace!"

Finally, Jesus, as king, messiah, and deliverer models this way of life to the point of death on a cross. Refusing to accept the lure of power through military might or pursuing peace through violence, Jesus embodies the life of suffering and self-sacrifice that he is calling his followers to emulate. Jesus, as the ultimate peacemaker, shows us that the life and work of peacemaking isn't some fairy tale euphoria, but the gritty, subversive and sacrificial life of faithfulness to a God and kingdom that lives by a different standard than the systems and powers of the world.

GORDON COSBY was perhaps the most Christian human being I have known. But he would always be the first to raise serious questions about what it meant to be a “Christian” and lived a different life than many of his fellow pastors and church leaders who call themselves Christian. Gordon was happier just calling himself a follower of Jesus. He always told people who wanted to call him “reverend” to just say “Gordon.”

Julia Ward Howe, best known for writing "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" in 1862, began working to heal the wounds of the Civil War once the war ended. By 1870 Howe had become convinced that working for peace was just as important as her efforts working for equality as an abolitionist and suffragette. In that year she penned her "Mother's Day Proclamation," exhorting women to:

“Say firmly: ‘We will not have great questions decided by

irrelevant agencies.

Our husbands shall not come to us, reeking

with carnage, for caresses and applause.

Our sons shall not be

taken from us to unlearn all that we have been able to teach

them of charity, mercy and patience.

We women of one country will be too tender of those of another

country to allow our sons to be trained to injure theirs.

From the bosom of the devastated earth a voice goes up with our own.

It says "Disarm, Disarm! The sword of murder is not the balance

of justice.’"

Last year, 506 murders happened in the city of Chicago — the majority of them in black communities. Similar rates of violence swept through places like Philadelphia, Camden, N.J., New Orleans, and the list could go on and on. I have in my life begun to declare myself a pacifist. I have made this change because I think, as a black man, the only recourse for me is to try and stop violence that happens in so many black communities. Turning the other cheek, responding with a gentle answer, forgiving a misunderstanding: these are the paths to recovery in my neighborhood.

The “if someone hits you, hit them back” mentality is destroying black men at an alarming rate. Dads, teach your boys to talk it over, look the other way, or keep walking when things begin to escalate.

The Rev. Bob Edgar, a Democratic congressman and United Methodist minister who went on to lead the National Council of Churches through a painful series of restructuring, died suddenly Tuesday at age 69.

The man religious leaders remembered as a “bridge builder,” suffered a heart attack and had been exercising on a treadmill in his home in Burke, Va., said Mary Boyle, spokeswoman for Common Cause. Edgar became president of the Washington-based nonpartisan advocacy group in 2007 after serving two terms as the general secretary of the NCC.

“He was a man of great capacity who understood the importance of cross-cultural and religious dynamics,” said the Rev. Carroll Baltimore, president of the Progressive National Baptist Convention, who recalled traveling in a Common Cause interfaith delegation Edgar led to Vietnam in 2010 to learn about continuing effects of Agent Orange.

Baltimore said Edgar brought together Christians, Buddhists, Confucians, and political leaders.

“He was able to link all of those pieces together and just remind us that we’re all made from the same cloth,” he said.

“Be still and know that I am God.” - Psalm 46:10a

From April 29 to May 5 individuals, households, and communities will celebrate Screen-Free Week by disconnecting from their screens — TV, computers, games, mobile devices — during their free time and reconnecting with relatives, neighbors, the natural world, and the quiet voices that may be drowned out by the constant barrage of electronic noise. My neighborhood celebrated early so we could offer a variety of cost-free and screen-free family activities during the school's spring break week. I organized the celebration, as I've done for the last six years. It was satisfying to see kids slow down and engage in gardening, carpentry, music making, nature exploration …

I also observed Screen-Free Week myself. Seven days of fasting from electronic media showed me how much time I spend using then mindlessly and forced me to confront my idolatries that are fed or masked by this mindless use. I'm using Michael Schut's definition of idolatry:

"An idol is anything we put before God, a partial truth mistaken for the whole Truth, a lesser good elevated to the ultimate good. … Idols [promise] what they cannot deliver."

The question for me as a teacher is not so much "What could have been?" as it is "What can be?"

I think of my fourth grader holding signs that say, "I am MLK," "I am Anne Frank," "I am Harvey Milk," "I am Daniel Pearl," "I am James Byrd, Jr.," "I am Matthew Shephard," and "I am Yitzhak Rabin." Though she cannot really be them, she certainly can take up their work and carry it on in her own life. She wants to become a doctor so she can help people live. With that spirit, she will help these martyrs live, too.

As a teacher, it is my job not only to help students imagine a world without hate, but also to help them find the tools and the heart to build it.

I woke up this morning, like everyone else, to the news of a shootout with one suspect in the Boston Marathon bombing and the ongoing manhunt for a second brother. Like many others, I’ve heard lots of misinformation over the past few days about whether officials did or didn’t have a suspect, whether they did or didn’t have them in custody, and so on.

“I heard someone dropped a bomb on Boston,” said Mattias, my 9-year-old son, over breakfast while I scrolled through the breaking news reports.

“Not exactly,” I said. “It was two guys. Two brothers who came from [another country] to go to college at MIT.” They put homemade bombs in and around trashcans by the finish line of the marathon.”

“Why?” he asked.

“I really don’t know.”

“Maybe they were angry about something, and they didn’t know how to talk about their feelings.”

“Maybe so,” I nodded.

“Did they hurt people?”

On April 11, 1963 Pope John XXIII published an encyclical some initially dismissed as naive and myopic, as too liberal and too lofty. But today, his "Pacem in Terris" is generally lauded as genius and prophetic – well ahead of its time on the issues of human rights, peace, and equality.

As Maryann Cusimano Love, a Catholic professor of international relations, notes, the same year “Pacem in Terris” was published, spelling out the theological mandate for political and social equality for all people, women in Spain were not allowed to open bank accounts, Nelson Mandela was standing trial for fighting apartheid, and Walter Ciszek was serving time in a Soviet gulag simply for being Catholic.

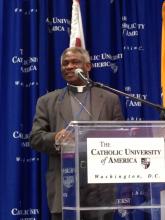

On Monday and Tuesday, the Catholic Peacebuilding Network hosted a two-day conference at the Catholic University of America, commemorating 50 years since the publication of "Pacem in Terris.”

My Uncle Norman fought in Europe during World War II. An artillery observer, he didn’t return with many “heroic” stories to tell. When I was little, he would roll out some souvenirs from the war, and I’d be impressed: German military dress knives and lovely table linens. I don’t recall all of the stories or how these things became his, but I’m pleased to report the table linens were a gift. His war experience was hardly glamorous.

Uncle Norman did tell of one harrowing experience. He and his partner were identified by German artillery, and they experienced exactly the treatment they dished out. Out in front of their own unit, as they always were, they heard a shot go just overhead and explode behind them. Then one fell just short. Placing a shell a bit to the left and one to the right, the Germans had them zeroed in. Uncle Norman’s friend panicked, frozen, stuck to the ground. And in the last minute – as he remembered it – my uncle tackled his partner and carried him to safety. Pretty dramatic stuff for a kid to hear.

When Uncle Norman was much older, he came close to death after gall bladder surgery. That night he experienced profound nightmares, the Lady Macbeth experience of bloody hands he could not cleanse. The next day, he told me a very different story than the ones I’d heard before. I believe I was the first to hear of the time when he called in the coordinates for an intersection across which a significant body of Germans was crossing. For 30 minutes, he said, he watched the effects of the barrage he had targeted. And now, 40 years later, his hands wouldn’t come clean.

IT'S BEEN SAID that one of the most radical things Jesus did was to eat with the wrong crowd. Undoubtedly, folks on the Left were frustrated with Jesus for making friends with Roman tax collectors. And folks on the Right were surely ticked at him for hanging out with Zealots. Dinner must have been awkward with both of them at the table; after all, Zealots killed tax collectors for fun on weekends.

But Jesus was a subversive friend, a scandalous bridge-builder, a holy trespasser. Just as we are known by the company we keep, so was Christ—accused of being a "glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners" (Luke 7:34). He was put on trial for being a rabble-rouser and a traitor. He got in trouble with the religious elite for crossing the line, overstepping purity laws and cultural norms, and disrupting the status quo. His love had no bounds and his friendships defied categories. He insisted on calling his followers friends: "I no longer call you servants, because a servant does not know his master's business. Instead, I have called you friends" (John 15:15).

Jesus made friends—with folks who adored him and folks who hated him. He sat with the woman at the well, washed the feet of his disciples, wept at the death of his buddy Lazarus, and loved his mom and dad. But his love went beyond borders. He redefined family, inviting his followers to be "born again" and discover an identity that runs deeper than biology. He challenged the chosen and included the excluded—in the family of God.

I wonder who Jesus would be hanging out with if he were around today?