Church

A church and mosque in France’s “jungle” camp for migrants and refugees have been destroyed, despite authorities’ reportedly promising not to demolish the places of worship. Bulldozers moved into the camp in Calais, the departure point for ferries to Great Britain, on Feb. 1 and tore down the mosque, which reportedly drew up to 300 worshippers each day, and St. Michael’s Church, a makeshift chapel serving mainly Orthodox Ethiopian Christians.

Apparently, Bigfoot wears glass slippers. And he lost one in Taiwan.

That may be the conclusion passers-by would come to when seeing this new church in Taiwan’s Jaiyi County, but in reality, the intention is to attract women worshippers.

December means curtains up for church Christmas pageants, hand-bell concerts, caroling kiddie choirs, and Nativity displays on the front lawns.

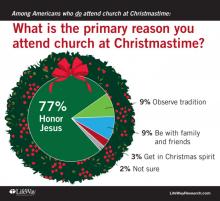

But the No. 1 reason most U.S. adults — Christians and many unbelievers, too — give for going to church at Christmastime is to “honor Jesus,” according to a new survey from the evangelical research agency LifeWay Research.

More than three in four of churchgoers (77 percent), Protestants and Catholics alike, said they were drawn to attend church to honor the birth of their savior, the fundamental religious experience of Christmas above and beyond all the seasonal fa-la-la-la-la.

I spend (most of) my Sunday mornings sitting in a pew at an Evangelical Lutheran Church in America congregation, singing old hymns, and reciting the Lord’s Prayer which I have had memorized since before I went to school.

At age 22, I make an effort to get my dose of word and sacrament before heading to brunch on Sunday mornings. Though I love the beach, I found greater joy in singing songs and leading Bible studies at a mainline church camp during my recent summers.

I love the sound of an organ.

Do not be alarmed: there are no known bands of Jesus fish-sporting, vigilante hackers patrolling the cyber underworld.

But in 13 cities this weekend — including Jakarta, Bangalore, Addis Ababa, Guatemala City, London, Waterloo, Atlanta, and Raleigh-Durham — more than 800 Christian coders, developers, programmers, designers, pastors, and artists gathered together for a 48-hour simultaneous hackathon. They scripted, designed, collaborated, and competed to develop new apps and websites for global and local adherents to the faith.

Programmers speaking of transformational love, and pastors wielding code: Welcome to the first global Christian hackathon.

In two wide-ranging new interviews, the pontiff discusses matters both weighty and personal, such as: the perils of his popularity, his plans to welcome divorced and remarried Catholics, and his fear that the church has locked Jesus up like a prisoner.

Speaking Sept. 13 to the Argentine radio station, FM Milenium, Francis lamented those who posed as his friends to exploit him, and decried religious fundamentalism.

And speaking to Portugal’s Radio Renascença in an interview that ran on Sept. 14, Francis said that a priest comes to hear his confession every 15 to 20 days: “And I never had to call an ambulance to take him back in shock over my sins!”

THE KILLING OF 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., last year and the events that followed sparked protests by the community in the St. Louis area asserting that black lives matter and ignited a discussion on race relations in the United States.

On the heels of non-indictments in the slaying of Brown and other black men, our nation focused its attention on the drastic inconsistencies inherent in our judicial system. To many observers, black lives had less standing in our nation than white lives.

Rodney King, Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, and the churchgoers in Charleston, S.C., are part of a long list of black victims of violence. They are victims of an American narrative that devalues black souls, black lives, black bodies, and black minds. In response to these tragic events, particularly since the non-indictment of the police officers who killed Brown and Garner, many evangelicals have been calling for a biblical practice that is often absent in American Christianity—the call to lament.

On one level I am thrilled that evangelicals are discovering the importance of lament in dealing with racial injustice. However, I am concerned that the way lament is being used by some white evangelicals is a watered-down, weak lament that is no lament at all.

Lament is not simply feeling bad that Brown won’t be able to go to college. Lament is not simply feeling sad that Garner’s kids no longer have a father. Lament is not asserting your right to confront the police because, as a white person, you won’t be treated in the same way that a black protester may be treated. Lament is not the passive acceptance of tragedy. Lament is not weakly assenting to the status quo. Lament is not simply the expression of sorrow in order to assuage feelings of guilt and the burden of responsibility.

“BLACK WOMEN AND GIRLS are killed by the police, too.” I can’t tell you how many times I’ve received a blank stare when I made this statement, even in activist spaces. Occasionally I’ll see a few affirmative nods, but overwhelmingly there is apathy. I leave with a sick feeling, wondering, “Where is the rage and protest for my sisters?” and “Who will fight for my life?”

In May, Black Lives Matter, Black Youth Project 100, and Ferguson Action came together for a national day of action for black women and girls. We wanted to shed light on the fact that black women and girls, in all our complexities, have been erased from the broader narrative of police terrorism and modern-day lynching in this country. Cities such as Oakland, Calif., New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, and Miami all participated in powerful acts of public resistance that involved reading the names of women who have been killed by police and using the hashtag #SayHerName as an awareness tool on social media.

Speaking our sisters’, daughters’, and mothers’ names at a vigil on a day set aside to acknowledge our humanity is powerful, because it says: When the world has forgotten Mya, Aiyana, Tanisha, Rekia (and so many others), we will not forget.

“THE IDEA THAT peace is inevitable is as dangerous as the idea that war is inevitable,” says author and peace educator Paul K. Chappell. We’ve been discussing peace in practice for the better part of an hour, and he’s warming to the theme. He puts forward an unlikely premise—that violence is not intrinsic to human nature.

Paul Chappell isn’t what you would expect in a peace champion. A graduate of West Point and a member of the U.S. military for seven years, including as a captain in Iraq, he first honed his fighting skills on school playgrounds, getting expelled for fighting in grade school and suspended in high school. He was bullied as a child for his skin color (his father, a veteran of the Korean and Vietnam Wars, was biracial—black and white—and his mother is Korean). Because of his father’s war trauma, Chappell describes his childhood as “unpredictably violent.”

It’s hard now to imagine this former troubled youth, both perpetrator and victim of violence, as the articulate Chappell thoughtfully winds his way through classical theory and national myth. But Chappell’s learned taste for creed over instinct is clear. The army provided the closest thing to family that a young Chappell had ever encountered, he tells me, but despite that deep affection—or perhaps because of it—he began paying attention to the lasting effects of war and trauma on his brothers-and-sisters-in-arms.

The move would bring London into line with Paris and New York, where no restrictions on Sunday shopping exist.

Strict anti-Sunday shopping laws came into being in the 19th century, under Queen Victoria.

In 1986, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher tried to do away with them but she met stiff opposition from traditionalists and Christian churches.

Two decades later a compromise was reached, and most shops are now allowed to open for six hours on Sunday.

Church leaders, I beseech you to study all sides of the situation carefully and prayerfully before you make a judgment on your church member that may alter his or her view of God or spiritual life forever. You have been placed in such a position to be the agent of change, to bring restoration to the individual.

As someone who has felt the sting of this, I ask you to consider these questions: Are we equally investigating BOTH parties? Are we taking the totality of the word of God into examination on this issue? What is the Holy Spirit telling us to do? Does Satan have a foothold of pride or control in my heart?

Religion is notoriously behind on nearly every societal curve there’s ever been. Some say that’s a good thing, as it’s supposed to be countercultural.

But there’s a difference between pandering to cultural trends and being tone-deaf or willfully ignorant. And as one of my old grade-school counselors once said: when you know better, do better.

If we look around us we know that there are better ways to employ the resources we have to affect positive social change, deepen discipleship, and strengthen community of many kinds. But we adhere to mid-twentieth-century models and understandings of how the world works, then look around, asking ourselves why no one cares anymore.

It’s time for Moneyball church.

We looked at the famous photo of Earth taken from Apollo 8. If you remember, it was the first time we got to see ourselves from the vantage point of another body in space.

The boys wondered why the photo was so grainy. I told them it’s from the 1960s. They seemed to think those were prehistoric times and started talking about pixels.

I told them that the grainy photo of Earth kind of fits what we do at church. We try to help each other find God in this picture. Sometimes when it seems that God is nowhere to be found, we just have to look a little closer and recognize the divine everywhere.

The issue isn’t that God does not have power; the issue seems to be more that we do not use the power that God gave to us. While we profess to love God and God’s son Jesus, we are all too ready to dismiss what God gave us in, with, and through the life, death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus. While we say we are Christian, we bypass too often the words of Jesus and latch onto other parts of the Bible, most often the words of Paul. While Paul’s writings have their own power, they do not have the power of Jesus’ words, nor do they carry with them the promise of the Holy Spirit, which does have the power to sustain and strengthen us.

Bio: Erika Totten is a leader in the Black Lives Matter movement in Washington, D.C., and the black liberation movement at large. She is a former high school English literature teacher, a wife, a stay-at-home mom, and an advocate for the radical healing and self-care of black people through “emotional emancipation circles.”

1. How did you get started with “emotional emancipation” work?

Emotional emancipation circles were created in partnership with The Association of Black Psychologists and the Community Healing Network. I was blessed to be one of the first people trained in D.C. I had been doing this work before I knew what it was called. My organization is called “Unchained.” It is liberation work—psychologically, mentally, spiritually, and emotionally.

I want to tell people to be intentional about self-care. Recently, we had a black trans teen, who was an activist, commit suicide. A lot of times you need to see a counselor or therapist, which is often shunned in the black community. Because of racism, we are taught that we need to be “strong.” But it’s costing us our lives. As much as we are dismantling systems, we have to dismantle anything within ourselves that is keeping us from experiencing liberation right now.

Goodpasture Christian School sits on a sprawling, bucolic campus seven miles north of downtown Nashville, where 900 students ready themselves for adult lives of college, career, and loving the Lord.

Right next door sits the United Fellowship Center, a planned church where adults will ready themselves to have sex with each other after enjoying a little BYOB togetherness.

It’s the newest incarnation of The Social Club, a whispered-about swingers club in downtown Nashville that left for the suburbs when a building boom took its parking lot. The community went bonkers after zoning hearings revealed the club’s plans to relocate in a former medical office building in Madison — adjacent to Goodpasture and within a mile of an Assemblies of God megachurch.

After months of debate, an emergency city zoning amendment and a state law designed to stop the relocation, the club’s attorney made an announcement: The Social Club would open in its new location as a church.

Protection via the First Amendment effectively silenced zoning complaints — for now. But it sparked conversations about what it means for a secular organization suddenly to label itself a church, and religious scholars seem no more ready to plunge into that debate than American courts have proved to be.

“When I see this case, I do roll my eyes, but I also know Protestant Christians in America don’t own 'church,'” said Kutter Callaway, assistant professor of theology and culture at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, Calif.

I am in a lovely college town to help a congregation discern its path forward.

It faces challenges that many church leaders will recognize: leadership, finances, isolation from the surrounding community, not enough young and middle-age adults to carry the congregation forward.

It also has pluses. The members aren’t deeply divided or mired in distrust and disdain. They aren’t afraid of change. They don’t bury the future in grand laments about a lost “golden age.”

I think they have a good shot at turning a corner and building a healthy next phase. I hear reports from across the nation that things are improving for Christian congregations. A new generation of clergy is exploring new ideas. Fresh energy is emerging. Denial is losing its hold, as congregations whose average age is 60 to 65 realize they must change or die.

Denominations are slower to adapt, but they, too, are moving forward in practical ways such as training in leadership and stewardship, and flexible deployment of resources.

Yet for this fresh day to last, church leaders will need to embrace a truth that goes beyond organizational development and resolving present issues. It’s a truth that many congregations simply cannot hear.

That truth is this: There is too much shallowness, not enough depth.

Over the years, in a process that isn’t at all unusual, we have equated faith with attending Sunday worship, maybe pitching in on a committee, and forming friendships within the fellowship. People enjoy belonging to the congregation. They radiate a palpable joy in being together. They seem content.

WHEN I WAS 15, my church youth group was not a safe place. Like most youth groups, there were college-age volunteers who served as counselors and Bible study leaders.

One counselor, Paul, took it upon himself to constantly tell me I wore too much makeup, my clothes were too tight, and that I was a flirt. These actions took place in public for six months while other counselors and students watched and laughed. The interactions came to a head when he commented on my lipstick color and I snapped back at him. He grabbed me, forced me onto his lap, and told me I liked it.

At the time, I just thought Paul was creepy; I now recognize his behavior was sexual harassment. I also recognize that the other members of my youth group, including the leaders, saw his behavior and failed to intervene. Why did this happen? Both Paul’s behavior and the leaders’ silence belong to a larger set of attitudes in our culture—and churches—that allows sexual violence and sexual harassment to become normal, even expected, behaviors.

This set of attitudes is known as “rape culture.” When we fail to confront these toxic attitudes in our churches, we undermine our love for our neighbors, ignore the Bible, and misrepresent God as misogynistic.

A sheriff in one of North Carolina’s smallest counties told registered sex offenders they can’t go to church, citing a state law meant to keep them from day-care centers and schools.

Graham County Sheriff Danny Millsaps told sex offenders about his decision Feb. 17, according to a letter the Asheville (N.C.) Citizen-Times obtained March 6. About 9,000 people live in Graham County, which abuts Great Smoky Mountains National Park on the Tennessee line in western North Carolina.

“This is an effort to protect the citizens and children of the community of Graham (County),” he wrote.

“I cannot let one sex offender go to church and not let all registered sex offenders go to church.”

He invited them to attend services at the county jail.

I WAS ONCE told that “racism is our nation’s original sin.” This statement jolted me. While I didn’t dispute its truth, I have come to realize racism is much more complex than this.

In order to dismantle the structural sin of racism, we have to first set it within a larger context that acknowledges racism’s sociopolitical dependency and structural interconnectedness.

First: “race” is not real. It is not a scientific category; biologically, it does not exist. Race is a social construct, something built systematically. It has no inherent value or true significance beyond what we give it. In order for race to have real social consequences—which it undoubtedly does—there must be other phenomena at work that validate, sustain, and reinforce the social significance of race.

As a result of sin in our fallen world, human bodies are appraised and given a value based upon certain criteria. As a result of sin, men are privileged over women, white skin is privileged over darker skin, able bodies are privileged over disabled bodies. Historically, certain bodies are acclaimed while others are defamed. Race plays a starring role in this larger drama of embodiment.