Church

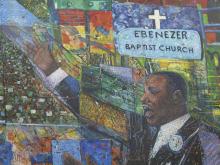

What is at stake in the conversation regarding the decline in religious life is not just the future of our faith institutions but the future of humanity. We are living through a time just as Dr. King described, where reactionary forces seek to double down on the failing status quo through the rhetoric of scarcity, isolation, and walls. In response, a prophetic faith kindles the imagination of humanity helping us to create new pathways to respond to the challenges of our time that are rooted in not in fear, but in possibility and the values of justice and peace.

As Shamika and I called upon our own experiences in church and seminary, we became especially concerned with providing a resource for those who historically have been barred from participation at the Lord’s Table: the divorced, Christians of color, LGBTQ believers, those living far from physical community, or far from a church that is physically accessible. While we’re not trying to replace “brick and mortar” community, we believe God calls us beyond a spirit of fear in the face of innovations in technology.

Christians can claim that God's power is made perfect in weakness but leaning more heavily on the image of a mothering God would push Christians to give the care-giving traits a higher value at the ballot box and in our advocacy work.

In our faith walk, there is much to celebrate, but insistently characterizing life as a triumphant march from glory to glory can alienate people who don’t find life quite as sunny. Church culture can feel painful for people who deal with various health issues or certain kinds of inner suffering that make it difficult to sense God’s presence. There’s little discussion in church of the “dark nights” that are a normal part of the faith journey, or the fact that such nights can last for years in some cases.

In that small town, we were told that we were in "God’s country." The physical and spiritual evidence that surrounded us made us all the more certain. If this was "God’s country," then this too was God’s community, God’s actions, God’s relationships. The community, its actions, its families, its relationships were sacred. Nearly every aspect of the community was transformed into some great action of the Kingdom. And we were reminded, almost as often, that The World was a threatening force trying to make its way in and it was our duty to keep it out.

As a multiracial Christian, growing up in white evangelicalism challenged my sense of belonging. Fitting in was dependent on how well I could match the church culture. Minorities understand that being accepted by the dominant culture means living out a characterization of ourselves rather than our whole selves. We must think and act with sameness to the dominant church in order to belong.

Where are the safe and brave church spaces for Christians of color?

So now, here the church sits staring in the face of human rights violations being committed in our national name. Here we sit privy to the betrayal of anything we could possibly claim the gospel to be about — from the actual life story of Jesus and his dark-skinned, refugee family to the theological imperative to love one’s neighbor and stand with the most vulnerable. Here we sit bearing witness to breathtaking levels of racialized, religious violence being emboldened by this administration’s rhetoric and policies.

I spent the first 18 years of my life blissfully assuming all Protestant churches allowed women to preach. At my home church, a tiny Presbyterian (USA) congregation in San Antonio, women spoke from the pulpit as often as they brought lukewarm casseroles to Sunday potluck. But when I left home for college, another first-year ambushed me in the dorm kitchen with his mouth full of 1 Timothy, bursting my egalitarian bubble. While I have since memorized the scriptural justifications for my equal existence and participation in the church, a new study by Church Clarity reveals that I am still far from living in a world where all Protestant churches allow women to lead.

AT THE BORDER between San Diego and Tijuana, Mexico, people come together once a week for communion across the dividing line. El Faro: The Border Church/ La Iglesia Fronteriza is held every Sunday on both sides of the border. For some families, it is their only opportunity to see loved ones who have been separated from them by immigration status.

The service is at Friendship Park, or “El Parque de la Amistad,” the piece of land that lies between the mesh border fence and the larger border wall that keeps the United States separate from Mexico. Usually, the outer wall is closed, cordoning off any opportunities for people on opposite sides of the border to connect. But for four hours each weekend it opens. For most people, the border is a place of division. But for Pastor John Fanestil, the borderland, or “la fronteriza,” is “a place of encounter.”

Fanestil, who preaches at First United Methodist Church of San Diego, has been running El Faro: The Border Church for almost a decade. He meets me at the trailhead of Border Field State Park, the 1,000-plus-acre San Diego nature preserve that borders the sprawling metropolis of Tijuana. In the summer months, you can drive all the way down to the border, but the trail floods when it rains and is often closed to vehicles in the winter. Today, it’s shut because of a sewage spill from Tijuana, so we hike down.

Fanestil was raised in La Jolla, an upscale neighborhood in San Diego, but says that his first real introduction to Spanish culture was in Costa Rica, where he did a year of seminary. His first appointment after ordination was in the inland border town of Calexico, Calif., which is adjacent to its Mexican sister city, Mexicali. He fell in love with the border culture, and after serving congregations in Los Angeles and Orange Country, he was placed in San Diego in 2004.

For too many Christians, the argument that we should love others because Jesus told us to becomes a begrudging obligation rather than a willful choice. If the only thing that drives Christians to accept disenfranchised people is Jesus, there is a lack of authenticity in that connection. The implication is that without Jesus, there would be no intrinsic value to diversity.

I think Christians have to do organizing, because it helps us to broaden whatever kind of tunnel vision some of our own traditions unwittingly produce in this fundamentalist age. I often tell my congregation that organizing, justice work, is essential for Christian discipleship, because it helps our heart become less wicked. It puts you in relationship and conversation with both systems and individuals that you may need to learn from, or you may need to help transform. I think organizing is critically important in that way.

And nearly every Sunday, as broken bread stands for broken bodies, I am struck with the words of James Baldwin, when he wrote that to be born black or a person of color in America means that you must “give up all hope of communion.”

When Baldwin wrote those words he believed that the nation was both a Christian nation and a white nation. White supremacy was the foundation of American rites and rights. Whiteness was a prerequisite to be encircled by compassion and included in citizenship. The denial of communion — the denial of the body of Christ and the rejection from the body politic — was connected to the nation’s original sin.

As I look back, I can now see how these transitions had been significant in my caminata espiritual as well as in discerning my call to serve God and God’s people. These different encounters with places, peoples, and cultures, have been crucial in my attempt to foster the conditions for visible signs of Jesus’ kingdom to be a present reality and not only an eschatological affair.

The report cited 301 priests who are accused of abuse. As a consequence of the cover up, only two priests are subject to prosecution — some abusers died and other cases are too old to prosecute. There were more than 1,000 victims identified in the report, mostly boys, but more victims are believed to exist.

These recent events have catalyzed a movement, inspired by the leadership of members of color at First Congregational Church in Oakland, Calif., to encourage churches to divest from police. This means churches will stop calling the police and will start hosting activities to promote alternatives, such as restorative justice circles, self-defense classes, and mental health de-escalation trainings.

This leaves people of color and indigenous peoples trying to decide if it's worth it to participate, if we can handle another conference, if we can possibly share our stories to a room willing to listen first and do the work later. It is an honor to share our stories, but there is a weight along with it. There is energy expelled from our hearts and bodies when we say this is my story, this is what my ancestors endured to give you America.

“Sparks were flying all around the table, and then Jared had this idea,” Moore said. “He said — it was a brilliant idea, and this was the impetus, the beginning of things — ‘What if we got every church or synagogue to take responsibility for one prisoner re-entering society? You think that could work?’”

But since the 2016 meeting, many of its smaller U.S. jurisdictions and regional bodies, called annual conferences, have made their own decisions regarding LGBT clergy. Last year, the Mountain Sky Conference elected Karen Oliveto, a married lesbian, as the denomination’s first openly LGBT bishop.

Times reporter Edward B. Fiske observed how conservative evangelical Protestants supported the war. Many, like the theologian and editor of Christianity Today, Carl F. Henry, believed it to be morally defensible. Fiske wrote that “the majority of laymen and clergy in this country” were more in agreement with Carl Henry than with William Sloane Coffin.

A crowd of thousands of angry, shouting protesters gathered as his body, covered by a sheet, was carried on a makeshift stretcher along dirt streets to the presidential palace, a Reuters witness said.