Commentary

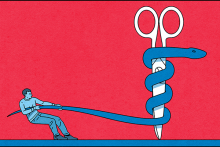

SINCE PRESIDENT TRUMP urged Texas lawmakers to get him “five more seats” in the House of Representatives before the 2026 mid-term elections, the words “redistricting” and “gerrymandering” have grabbed news headlines. Texas has redrawn congressional districts to give the Republican party an advantage. California is leading a countermove to redraw districts to give Democrats an edge. Other states are considering similar ploys along partisan lines.

Redistricting is the process of revising the boundaries of districts from which legislators are elected. Normally, redistricting takes place once a decade following the national census. Using new data on population changes and racial diversity, each state is required to redraw voting districts to provide balanced populations for congressional and state representation.

Gerrymandering happens when redistricting goes rogue. The word dates from 1812, when Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry permitted a congressional district map drawn to benefit his own party. One district, shaped like a monstrous salamander, caught press attention. Ever since, distorted districts have been called “Gerry-manders.”

FOR THE THIRD year in a row, Advent in Palestine is not a season of joy. Even with the tenuous ceasefire, Advent is lived in the shadow of genocide, walls, checkpoints, ethnic cleansing, dispossession, and fear.

For many Palestinians, these days of waiting and preparation are overshadowed by mourning for loved ones lost, for homes demolished, for lands taken. In Bethlehem itself, where the Christian story began, streets that should be filled with song and light are burdened with grief and lament. The hymns of waiting mingle with the cries of the bereaved, displaced, imprisoned, and the starving.

In the land where the gospel of Jesus first unfolded, the nearness of Advent is most real. The Christmas story doesn’t look like comfort, plenty, and “toys in every store.” The original narrative bears a much closer resemblance to the times in which we, Palestinians, currently live.

THE VAST AGRICULTURAL plain of Ventura County in California, where César Chávez first envisioned the United Farm Workers movement, is no stranger to grassroots activism. When federal immigration officers raided Glass House Farms in Camarillo on July 10, a rapid response network, the 805 Immigrant Coalition, immediately used its text app to mobilize citizens to protest and document the event.

“This is quickly becoming one of the largest operations since President Trump took office,” wrote Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem on social media as the chaotic raid unfolded, a raid that ultimately resulted in the death of farmworker Jaime Alanís Garcia.

“PRESIDENT TRUMP SAID he wants to destroy our holy ground of Oak Flat so a foreign-owned corporation can send copper to China,” Wendsler Nosie Sr., representing the grassroots group Apache Stronghold, told the Arizona Republic this summer. “Whether you’re Republican, Democrat, or neither, that is a terrible deal for the American people,” he said.

Trump called Nosie, and others who want to save Oak Flat, “anti-American” for defending the holy ground where San Carlos Apaches and Indigenous people worshiped long before there was a United States of America. Trump posted his comments on social media one day after the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals temporarily blocked the Trump administration from its plan to transfer the public lands of Oak Flat to Resolution Copper, a subsidiary of multinational mining companies Rio Tinto and BHP, and following a meeting between Trump and the CEOs of the parent companies.

Because Nosie’s people have worshiped the Creator for thousands of years while drawing water at Oak Flat, it is holy ground—a place for prayer and sacred ceremony, not unlike the Temple Mount for Muslims, Christians, and Jews. For Nosie, an elder in the San Carlos Apache Tribe, the wisdom of his people and their relationship with the Creator are inextricably tied to Oak Flat.

DECADES AGO AND an ocean away, there lived a dictator who called himself a president. From 1997 to 2003, Charles Taylor served a chaotic term in Liberia’s highest office, presiding over a civil war that killed tens of thousands of his own people and inflicted traumas like rape and child soldiering on many more. Taylor was later found guilty of “some of the most heinous and brutal crimes recorded in human history” by an international criminal court at The Hague.

Taylor’s regime was ended, in part, by the prayers of ordinary Liberian women. In 2002, a 30-year-old single mother and social worker named Leymah Gbowee awoke from a sleeping dream in which she believed she heard the voice of God say, “Gather the women to pray for peace!” Gbowee founded a series of public prayer meetings that eventually included thousands of women. Over the next few years, as the women demanded peace from God and from their leaders, Taylor was arrested, violence ceased, and Liberia elected Ellen Johnson Sirleaf as president, Africa’s first female head of state.

I first heard about the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace movement on the last Friday night of the Biden administration. Over dinner, a friend recalled hearing a talk about Liberia’s peace movement. “These women just stood outside the presidential palace,” she recounted, “and prayed until he was removed from office.”

The following week, as Donald Trump was inaugurated for the second time and his executive orders began to reverberate around us like so many gunshots, I couldn’t stop thinking about the Liberian women who prayed. What might it look like, I wondered, to do something like that here in America?

Budgets reveal our true values. Americans have long prioritized that everyone, including people with disabilities, have access to high-quality health care, essential long-term services, and nutritious food. However, the new tax cut and spending package signed on July 4, 2025, reorders U.S. budget priorities and creates significant hurdles to access or use Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act marketplace insurance. This new budget is designed to deny coverage to those who need it, even if they qualify, by burdening them with additional administrative and paperwork barriers.

Medicaid covers more than 70 million low-income or disabled people, including nearly half of the nation’s children. Congress slashed nearly $1 trillion from Medicaid, a staggering 20% cut, the largest in the program’s history. Approximately 11 million people will lose coverage. If Congress also fails to extend enhanced ACA subsidies, that number could rise to 17 million. New mandated work requirements for Medicaid recipients will result in more red tape and lost coverage. Medicaid is the primary payer for long-term supports, including home and community-based services, known as HCBS, that many people with disabilities rely on to live independently. Federal cuts mean that costs will shift to states, forcing them to reduce these “optional” Medicaid services.

The new law also cut nearly $200 billion from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the country’s largest food assistance program, and expanded its work requirements. People with disabilities are twice as likely to live in poverty as those without, so many depend on both Medicaid and SNAP. Imagine losing access to health care and food simultaneously.

If you’re a Medicaid or SNAP beneficiary or an organization supporting those who are, now is the time to learn how to defend benefits and demand your rights. Here are five essential actions you can take.

HOW IS IT possible that a major Christian denomination has refused to aid refugees from South Africa? Isn’t “welcoming the stranger” critical to a Christ-like response?

In May this year, the Episcopal Church refused to provide support and assistance to more than 50 white South Africans arriving in the United States to claim refugee status. The denomination took this action in consultation with and the support and endorsement of Rev. Thabo Makgoba, the Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, South Africa.

Despite the Episcopal Church’s nearly 40-year commitment to “seek and serve Christ in migrants and refugees,” it declared an end to its refugee resettlement contracts with the federal government because of Trump’s “white refugee” charade. To understand why the church’s refusal to resettle this group of white South Africans is not antithetical to the gospel, we need to take a closer look at the history of apartheid or racial segregation in my country.

THIS AUGUST MARKS 80 years since U.S. president Harry Truman issued orders to drop atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The impact was so terrible that no head of state has done so since. Yet, eight decades later, 12,000 nuclear weapons are deployed around the world — a veritable apocalypse-in-waiting.

While many people are accustomed to thinking of climate change as our existential threat, we may overlook that nuclear arsenals are the first global threat entirely of humanity’s own making.

WE WERE DEEP in the thick heat of a Virginia summer when my teenage campers gathered to argue one night on the volleyball court.

It was 2011 and I was a counselor at Camp Hanover, a Presbyterian summer camp and retreat center. It was my third summer working at the outdoorsy camp, and prior experience with campers told me this group was at a breaking point. The issue that divided them? Whether it was okay to be queer and Christian.

I had seen this group go through the first of the classic team formation norms (“forming, storming, norming, and performing” developed by psychologist Bruce W. Tuckman). I knew they were itching to storm. Sure enough, as we sat on the cooling sand of the court, stars piercing through the cloud layers above and the volleyball net swaying in the breeze, they finally opened up.

Some had pastors in their home churches who preached against queer affirmation. Some were queer themselves, grappling with their self-understanding in the context of their teenage faith. All of them were questioning what they had been told by adult leaders and were digging through their collective wisdom for answers.

That moment is the perfect illustration of why religious summer camps are important: They provide places for personal and spiritual growth beyond what kids can access in their regular home and church environments. Camp provides space — external and internal

I AM A grandson of the Black South, descended from women whose lives were shaped by the long arc of American contradiction. In her later years, my maternal great-grandmother, Essie Lou or “Big Ma,” would often sit alone on her back porch. If anyone came to check on her, she would say, “It’s just me and JC.” That phrase, soft-spoken and straightforward, testified to her resilience, her intimate relationship with the Divine, and her enduring hope. From another branch of my family comes Delsie, my third great-grandmother, born enslaved in 1831. She lived to see her son register to vote in 1867, during the fleeting promise of Reconstruction. Though from different branches, both women were shaped by the same Georgian red clay, the same struggle, and the same unshakable faith. Their lives spanned the distance between hope and heartbreak — and still, they believed.

Today, I believe we are living in another such moment — one that echoes the backlash against Black freedom and multiracial democracy during the so-called Redemption period. Then, as now, the church stood at a crossroads: complicity or prophetic resistance?

THIS YEAR, REPUBLICAN House Speaker Mike Johnson pushed through a budget resolution that calls for cutting at least $880 billion over 10 years from funding that includes Medicaid. A number of Republicans see these cuts as damaging to voters in their districts. Johnson’s job, however, is to advance the budget set forth by the Trump administration — a budget aimed at increasing spending on border security and deportations while also extending the tax cuts from the first Trump administration.

Those 2017 tax cuts saved households with incomes in the top 1% and the top 5% three times more than they did for those with incomes in the bottom 60%, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The Trump administration wants Medicaid to foot the bill, effectively stealing money from disabled children to give tax cuts to billionaires.

Medicaid is widely popular, but we can get so caught up in rhetoric and budget numbers that we fail to understand it. Broadly known as a joint federal-state health insurance program for low-income and disabled people, Medicaid also covers services for 47% of all disabled children in the United States. My daughter Zoe is one of them.

So is Mia, daughter of Adam and Joy Beth Crownover, who gave me permission to tell their story. Mia was born with lissencephaly, a condition in which the brain is smooth where it should be wrinkled. Many babies like Mia don’t live past their second birthday, but Mia is already 2.

SOME U.S. CHRISTIANS fear that the world is in chaos. These Christians have felt their cultural influence waning as our nation becomes more racially, religiously, and culturally diverse. This “chaos” extends to Sunday worship as once-robust congregations dwindle, tithing decreases, young people leave the church, and denominations split under the pressure of politically motivated culture wars. As someone raised in and deeply formed by the evangelical tradition, I have experienced this panic. It is terrifying.

In response, I’ve seen my Christian peers desperately attempt to control our world by donning red MAGA hats and aligning themselves with political strongmen and bullies. They attain positions of power in an authoritarian regime, place guards at the gates of “doctrinal purity,” and advocate for a Christian nationalism that elevates their rights at the expense of the rights of others.

The question we must ask, though, is if Christians should be in control. Is control the task that God has for us? Is gaining control over others the faithful way to worship God and act neighborly in this chaotic world?

But that does not mean that all control is bad. Wielding power and control becomes disordered when they are treated as ultimate goods. In “On Christian Teaching,” fourth century theologian Augustine of Hippo provides a helpful framework for this: “enjoyment” and “use.” To enjoy something is to treat it as the highest good — as an end in itself. To use something, then, is to put that thing in service to what we ultimately enjoy. God has given us some things to be used for the sake of something beyond them, while others exist to be ultimately enjoyed in themselves. The things that we enjoy, Augustine says, are what we ought to love.

IN MAY 1933, Nazi-influenced student groups publicly burned more than 25,000 books by Jewish authors and those deemed liberal or leftist in 34 university towns across Germany. Newspapers supported it as “action against the un-German spirit,” and Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s minister of propaganda, said to a crowd of 40,000 that “the era of extreme Jewish intellectualism is now at an end. ... The future German man will not just be a man of books, but a man of character.”

This antisemitic act of censorship and intolerance is memorialized at the Yad Vashem Holocaust History Museum in Jerusalem, where a display about book burnings sets the tone for the rest of the museum. Before you enter the display on the rise of Nazism, you must first consider the gravity of book burnings. A prophetic quote from 19th century German poet Heinrich Heine concludes the display: “Where books are burned, human beings are destined to be burned too.”

Across the city, in East Jerusalem, is the Palestinian-run Educational Bookshop. It consists of an English store, which doubles as a coffee shop, workspace, and community hub, and an Arabic store across the road. This family-owned business, which opened in 1984, sells all sorts of titles related to Palestine. There are Palestinian books on cooking, art, and history; there are novels, textbooks, and children’s books. The Educational Bookshop carries titles that are hard to find within Israel, and on a Sunday afternoon in February, this popular bookstore was raided by undercover Israeli police for the first time.

“They came into the shop with a search warrant,” Ahmad Muna, assistant manager of the shop, told me. “They demanded a search that happened over the course of two hours. The officers were aggressive, brutal, were not polite.” According to Muna, the officers didn’t speak Arabic or English; at first they used Google Translate to figure out book titles.

“At some point they had enough of Google Translate,” Muna said, “It was getting too tedious. So, they started to judge the books by their covers, by the design, by the picture on the cover, any book that had the flag of Palestine, any book that had a picture of a prisoner, of a boy being arrested, a picture of the wall, a picture of a Palestinian flag, it was confiscated.”

Police took away about 300 books in trash bags. Muna and his uncle were arrested and detained for two nights. After release, both were put under house arrest for five days and banned from entering their shop for more than two weeks.

I WAS STANDING at a bus stop in northern Virginia this spring with another dad putting his kids on the bus. He is a federal employee coping with the sudden precarity of the career he pursued to support his family. President Donald Trump’s executive order in February that directed federal agencies to submit plans for “large-scale reductions in force” may leave this dad out of work.

President Trump’s deployment of billionaire Elon Musk to dismantle the federal government fulfills a long-held dream for some. Since the mid-1980s, certain far-right Republicans have wanted to enact political strategist Grover Norquist’s mantra: “I don’t want to abolish government. I simply want to reduce it to the size where I can drag it into the bathroom and drown it in the bathtub.”

Well, “government” is “people.” Real people. There are 2.4 million federal employees, not including the military or the postal service. Under the Trump administration, they wake up each day not knowing whether the world’s richest man and the world’s most powerful man will decide that they no longer have a job.

Federal workers are only one sector in Trump’s bull’s eye. This administration is attempting to erase the existence of transgender and other gender-diverse people: A day one executive order proclaims that “it is the policy of the United States to recognize two sexes, male and female. These sexes are not changeable.” Trump has banned trans people from women’s sports and the military and now is attempting to eliminate gender-affirming medical care for people under 19. Immigrants are also facing a terrifying crackdown. Immigration enforcement officials arrested more people in the first 22 days of February this year than in any month for the past seven years, according to The Guardian. Green-card holders have been deported for their political activities. Immigrants accused of gang membership were flown to a maximum-security prison in El Salvador in open defiance of court orders.

AT TIMES, WHITE HOUSE press secretary Karoline Leavitt proudly wears a gold cross when meeting with the press pool. Many assume she emerges from the heart of right-wing American evangelicalism. But they would be wrong. Leavitt emerges from the heart of right-wing American Catholicism. While we have been focused on the fusion of evangelical Christianity and Far Right nationalism, we’ve missed how Christian nationalism has risen in Catholic and Orthodox traditions. Are former evangelicals — or “exvangelicals” — who resist Christian nationalism also contributing to its smokescreen?

“Christian nationalism” is an idea from academia that has become a bit overused. Fortunately, sociologists Andrew L. Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry provide a narrower, more workable definition. Christian nationalism, they write, is an “ideology that idealizes and advocates a fusion of Christianity and American civic life.”

In the past 50 years, this ideology has increasingly emerged as a visible force in American life, as the Religious Right walked onto the political scene and into the center of the Republican Party. For all that time, the image in the popular mind of the Christian nationalist has been stereotypically the (often Southern, but not always) white evangelical denizen of megachurches replete with rock bands and biblical literalism.

Colorado was one of the epicenters of that subculture, in part due to James Dobson’s Focus on the Family, based in Colorado Springs. I grew up in that region when the subculture was reaching its zenith in the 1990s, and it was clear that our evangelical neighbors did not think of my family’s Greek Orthodox faith as “Christian.” As a marginal minority in a context where evangelical Christians dominated the state’s cultural and political life, this experience prompted my interest in the history of religion; specifically, in how people construct idiosyncratic versions of history and identity for political ends. Over the years, I’ve watched the Religious Right morph into something new and virulent. Many of those raised in its most extreme cultures have migrated out of nondenominational evangelicalism to Orthodox Christianity or Catholicism. Others left Christianity altogether, joining the unaffiliated or “nones.” Many of the millennial (born between 1981 and 1996) and Generation Z (1997 to 2012) children of American evangelicalism became disaffected with their upbringing and the limited worldview it offered.

THE WORD “SERMON,” like “lecture,” is an ambiguous one: both a genre of speech and a shorthand for our worst ways of speaking to one another. Outside of a religious context (and to be honest, sometimes even inside one), who wants to be preached at?

Those connotations of arrogance and superiority likely come from authentic experience. But they also miss something important about the sermon as a genre: its foundation in humility, in the practices of reading, reflecting on, and speaking on someone else’s text.

In his 1990 farewell sermon as pastor of Concord Baptist Church in New York, Gardner C. Taylor, one of the great preachers of the civil rights era, asked for forgiveness “if I ever tried to make the Word of God mean what I wanted it to mean.” Sermons (in Christian tradition, as well as in my Jewish tradition) are public acts of commentary. And, as Taylor reminds us, serious commentary is a morally consequential act, because it requires putting one’s own priorities and intentions second to those of the text, an act which is always, at least a little, selfless. At the heart of a sermon is the tension between what the text seems to say and what the preacher wants to say with the text.

When I read or listen to a sermon — even one as politically memorable as Episcopal Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde’s sermon at the national prayer service following President Donald Trump’s inauguration in January 2025 — I try to keep that basic question in mind: What text is she preaching on?

IT SHOULD HAVE surprised no one when Donald Trump, who boasted to a New York City crowd, “On day one, I will launch the largest deportation program in American history to get the criminals out,” began carrying out his promise on Inauguration Day. Immigrants have been the target of Trump’s most aggressive rhetoric since he entered politics a decade ago, and he loves hyperbole. Trump is making the removal of migrants a centerpiece of his new administration by declaring a state of emergency on the U.S.-Mexico border, mobilizing National Guard units, and sending troops to do his bidding. The warlike imagery and language he uses are hard to hold alongside the Christian belief that we are all created in God’s image.

With approximately 11 million undocumented residents in the United States, there is legitimate reason to fear what Trump is enacting in his second administration. I say this as someone who witnessed what a Trump-appointed federal prosecutor called “the largest single-state immigrant enforcement operation in our nation’s history” during Trump’s previous administration. It occurred in 2019, in Mississippi, where I live. I know that whatever else happened that day, children were left without parents, families were cut off from loved ones, and communities were filled with a sense of confusion and terror. But I also know from that experience that, even in the worst moments, there were people and places where hope and comfort resided, too.

On day one, Trump began translating his campaign rhetoric to actual deportation methods. The point is sometimes made that Trump’s first administration deported fewer people than Biden’s or either of Obama’s administrations. While that may be accurate, context is everything. For example, deporting someone who just crossed the border illegally is very different from deporting someone who has lived in the U.S. for 20 years. While the numbers of people matter for each impacted individual and family, it also matters how people are targeted and why inciting terror is the tool of choice. Tom Homan, who Trump has chosen to oversee the nation’s borders, has said we should expect “shock and awe” from the current administration’s deportation efforts. That comment, coupled with Homan’s promise to conduct more workplace raids, suggests how deportations will be handled. That language calls to mind the workplace raids that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials conducted in Mississippi in 2019.

ON MARCH 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic of covid-19. The virus causing covid had already been circulating for at least four months. People were dying from some kind of strange pneumonia. In the five years since, our world has changed. As of December 2024, there were more than 7 million covid deaths worldwide (the actual number is likely three times that high) and 1.2 million were in the United States. The coronavirus has left an indelible mark on relationships, social institutions, and politics.

In 2025, we are still dealing with the shock and trauma of who and what we lost. Our sublimated grief, confusion, and anger too often manifest as personal denial, social apathy, or political individualism. All while the virus persists among us. For proper healing and to navigate this “new normal,” we must first square the last five years.

From the jump, the U.S. failed to provide an adequate pandemic response. President Donald Trump, in his first term, was handed an unexpected event — but not an unprecedented one. Preparations for a mass public health event were available, but by politicizing public health his administration left the country vulnerable. In 2018, Trump’s national security adviser oversaw the disbanding of the global health security team. Trump’s adversarial stance toward China, including increased tariffs, negatively impacted the supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) available in the U.S. In those first key months, the administration chose propaganda, not science, to fight the pandemic. In May 2020, Trump pulled the U.S. out of the World Health Organization (as he did again in January this year), which was coordinating a global response.

I WANT TO let you in on a joke. But, for many of us, this joke might not be funny for a very long time. Let’s begin by addressing the elephant in the room. The election results drastically exacerbated tensions that Americans have been struggling with for the last decade. As I write, holiday plans are being made and canceled based on who voted for whom. This tension is not going away soon. However, changes of political regimes and the Christmas story give us insight into where we are as followers of Jesus today.

As a pastor and a comedian, I try to bring God’s levity to bear on tragedy to recenter a Christian perspective. At its root, the word levity means “lightness,” like the word “levitate.” While God’s levity may not be conventionally funny in the moment, it employs the elements of comedy that, by design, lighten the burdens of our human experience.

FOR THE FIRST time, Americans have elected a wannabe dictator as president. Donald Trump is committed to and now capable of ending democracy as we know it. Trump is the one the “new authoritarians” have been waiting for. What now?

First, as of January 2025, the United States is on track to become an electoral autocracy. Electoral autocracies have multiparty systems and independent institutions that over time lose sufficient power to hold the executive branch accountable for its corruption or restrict its lawlessness. The Republican trifecta in November was not the presidency, Senate, and House. It was the White House, Congress, and Supreme Court. This win enables what political scientists call “state capture” by anti-democratic forces.

Whatever else we do, we must reorient our political map.