Commentary

ON SEPT. 5, the U.S. Department of State announced that it had secured the release of 135 political prisoners in Nicaragua. Among those released were 11 pastors of the Mountain Gateway ministry and a number of Catholic laypeople. These victims of the Ortega-Murillo regime’s sweeping persecution of religion will join hundreds of now stateless priests, women religious, bishops, and other believers exiled to Guatemala, Costa Rica, the United States, and even Vatican City.

Despite this negotiated release, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom still lists 36 Nicaraguans imprisoned because of their faith. That number does not include the thousands of Nicaraguans who have fled because of their beliefs or the more than 1,600 religious organizations and facilities that have been closed by the regime. Dozens of priests and ministers have been arrested. Religious charities, schools, universities, radio stations, churches, and clinics have been shuttered. Religious orders have been banned. Traditional religious processions for Holy Week have been outlawed. Secret police systematically monitor religious services. Even Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity were escorted from the country by armed police.

President Daniel Ortega’s authoritarian-trending-toward-totalitarian regime is powerfully repressing the Catholic faith and is rapidly expanding its persecution to Protestant and Indigenous faith communities. However, it was not always so.

I KNOW YOU. I met you in the dense canopies in the war in El Salvador. It was there that I first heard the single, high-pitched crack of the sniper bullet. Distinct. Ominous. A sound that spreads terror. I saw you at work in Basra in Iraq and of course Gaza, where on a fall afternoon at the Netzarim Junction, you shot dead a young man a few feet away from me. We carried his limp body up the road. I lived with you in Sarajevo during the war. You were only a few hundred yards away, perched in high rises that looked down on the city. I witnessed your daily carnage.

You targeted me, too. You struck down colleagues and friends. I was in your sights traveling from northern Albania into Kosovo. Three shots. That crisp crack, too familiar.

I know how you talk. The black humor. “Pint-sized terrorists” you say of the children you kill. You are proud of your skills. It gives you cachet. You cradle your weapon as if it is an extension of your body. You admire its despicable beauty. This is who you are. A killer.

THE LAST PICTURE in Richard Avedon and James Baldwin’s Nothing Personal, an exploration of American identity through the photographer’s eye and the essayist’s heart, holds a haunting some 60 years later. Two young boys look solemnly into Avedon’s lens. It is as if they stare into the soul of the watcher. It is as if in their innocence they wonder about the world in their silence. It is the children’s eyes that I can’t stop thinking about.

Their eyes are still our eyes, their gaze, still our gaze — weary, longing, determined, and despairing. Baldwin writes in the 1964 book, “Despair: perhaps it is this despair which we should attempt to examine if we hope to bring water to this desert.”

Baldwin and Avedon’s friendship and work together can be instructive for us because what we face as a nation is not much different from the Civil Rights years. We are presently dealing with a lack of trust; the forces of polarization are deepening within and without. There is, writes Baldwin, an “unspeakable loneliness” that we feel, wondering if anyone can feel what we feel and are angry about what we are angry about and are sad about what we are sad about. Then there is the kind of loneliness that takes root when “we live by lies.”

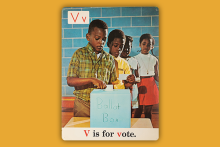

I PROUDLY SHARE the legacy of generations of people who fought to be respected as full citizens in America. I am the granddaughter of Mississippi sharecroppers. My parents picked cotton growing up, sometimes missing school to ensure the family could make ends meet. My parents left Mississippi in the late 1960s after college, having never voted. I know too well about voter suppression and the horrors of Jim Crow. The fundamental right to vote is close to my heart; it’s personal.

My generation was the first in my family born with full voting rights. I never thought the precious right to vote would be jeopardized in 2024. Yet, because the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013, the right of full and safe access to the ballot box is again impeded. Voter suppression has again taken hold as a tactic for dismantling democracy. The ghost of Jim Crow keeps on haunting.

IF WE ARE to end Christian nationalism, we must first develop a better idea of the threat we are facing.

Christian nationalism in the United States is a political ideology and cultural framework that seeks to fuse American and Christian identities. It suggests that “real” Americans are Christians, and that “true” Christians hold a particular set of political beliefs. It seeks to create a society in which only this narrow subset of Americans is privileged by law and in societal practice.

Christian nationalism is a gross distortion of the Christian faith that I and so many others hold dear. It employs the language, symbols, and imagery of Christianity, and it might even appear to the casual observer to be authentic Christianity.

GOD SEIZED ISABELLA on Pentecost 1826. Isabella Baumfree, born in slaveholding New York, had secured her freedom. But, in despair for her children, she “looked back into Egypt.” On the verge of returning herself to slavery, God’s spirit overtook her in a mystical encounter that changed her life.

This thunderclap of God’s grandeur surpassed any notions of the divine she had previously acquired. This God, at once familiar and foreign, called Isabella to abandon the faith of her owners. But God also called her to transform the faith inherited from her mother, who taught that survival consisted of equal parts prayer and submission to enslavement. As Isabella recovered from this mystical encounter her only words were, “Oh, God, I did not know you were so big.”

Seventeen years later, Isabella had another mystical experience. After having been swindled out of her savings, she struggled to rebuild financial stability in New York City. She asked herself why, “for all her unwearied labors,” did she have nothing to show? Why did others, with much less work and anxiety, “hoard up treasures for themselves and children”? As she reflected on the economic hardship she witnessed, she realized, “the rich rob the poor and the poor rob one another.” With this insight, the political roots of her religious transformation took hold. From that time forward she claimed a new name: Sojourner Truth. And began her career as a traveling preacher and activist.

POLITICAL SCIENTIST Thea Riofrancos has written extensively on the politics and economics of mining. “Extraction is a very old practice. We can say that it is as old as human history,” said Riofrancos in a Granta interview this year. With the rise of European empires in the 15th century, extraction led to conquest in search of valuable minerals. Conquest led to territorial occupation, consolidation of forced labor, and centralized foreign control over resources. And it is all still happening — now, on a planetary scale. This is why Pope Francis describes the Earth as the “new poor,” and thus as a locus of liberation.

The logics of extraction and occupation are entwined. Driven by economics, both view certain human lives, and any part of nature, as marketable and disposable by the cheapest means of violence and destruction. These logics thrive on the constant retraumatizing of the environment and of Black and brown bodies, to keep them compliant and prevent them from consolidating power. These are presented as necessary sacrifices for civilization to “advance.” Colonial laws remain in many post-colonial nations, and elite communities in those countries continue to benefit from resource control, perpetuating the violence and oppression of the colonial project.

In the age of climate collapse, these sinful logics come back to haunt us. For example, as the geographer Kenston Perry has highlighted, the Caribbean region has faced enormous losses from climate-induced natural disasters. This is a result of colonial systems that prioritized extractive plantation agriculture instead of protective ecosystems and disregarded Indigenous practices and knowledge of the environment. The fate of the poor, the marginalized, and those on the wrong side of western colonialism is inextricably tied up with the fate of the planet.

The environmental crises in Congo from mining and in Gaza from war provide two examples of how extraction and occupation are twin sins.

AS THEY GEARED up to storm the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, the soon-to-be rioters carefully chose their clothes, their flags, and their symbols to convey the message they wanted to send. That message, surprisingly, had a lot to do with Jesus.

One popular flag read “Jesus 2020.” Preachers and worship leaders arrayed around the Capitol “pleaded the blood of Jesus” while their compatriots shed the blood of Capitol Police officers. Indeed, at times the Capitol riot resembled a modern-day crusade, mayhem and suffering inflicted on the innocent under the sign of the cross.

I have spent the past three years searching out the leaders and theologies that galvanized Christians to show up that day. What I’ve found are networks of hardline Christian nationalists who have cobbled together a theology of power, domination, and privileged access. I call them “Christian supremacists,” because they are making moves to restructure society to privilege and elevate Christians over everyone else.

I wish I could say that these leaders were fringy, or better yet, not really Christians, but, if anything, Christian supremacy is spreading like wildfire in the American church, especially as we careen toward another polarized election.

The early church faced a similar problem: A group of early Christians called the gnostics believed that God gave special revelation to certain individuals, the spiritual elites. The gnostics disdained the more bodily and human dimensions of the biblical Jesus in favor of an enlightened, victorious Christ.

I HAD A conversation recently about an essay I’d written on prison labor in the United States. My colleague was shocked. Well into the 21st century, she mused, isn’t that a phenomenon reserved for totalitarian regimes on the other side of the planet?

It’s a reasonable assumption. After all, it sounds an awful lot like slavery.

The U.S. never abolished enslavement; we only regulated it. In 1865, the 13th Amendment to the Constitution ended legalized chattel slavery and involuntary servitude, except “as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” This proviso, known as the “exceptions clause,” has served to obscure the continuation of an American slave system from the end of the Civil War to the present day.

Convict-leasing schemes were integral to rebuilding the South from the ashes of total war. Incarcerated labor fueled the postwar Industrial Revolution. And today, approximately 800,000 of the country’s nearly two million incarcerated people work for a pittance (on average, less than a dollar an hour) with varying degrees of willingness. If U.S. prisons and jails were to form that workforce into a conglomerate, they would be the nation’s third largest private employer, behind only Walmart and Amazon.

IT FEELS AS though the United States could not become more polarized. Across our contemporary chasm, no matter what side people believe they occupy, the other always feels unreachable. That’s why this is a particularly apt time to ponder the late Rev. Will D. Campbell, who was born 100 years ago this July.

A white Mississippian raised in a 1920s Jim Crow thicket, Campbell rejected that era’s rampant racism early on. When the civil rights movement began, he embraced its goals with open arms. Campbell’s no-frills reading of the Sermon on the Mount led him to the cause. When 16-year-old Ernest Green and eight other African American students entered Arkansas’ Central High School in 1957, Campbell walked beside them. When the Southern Christian Leadership Conference came together, Campbell was the only white man in attendance. When the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee formed in 1960, Campbell made the first cash donation. To the brave leadership from the Black community, he added his own. For everyone involved, it was an extremely dangerous endeavor.

Then, at the midway point in Campbell’s life, his ministry underwent a drastic change. He set a controversial new direction for himself, one that confused many of his supporters and angered others. He began a soul-saving outreach to the white racists of the local Ku Klux Klan.

LIKE MANY ISRAELIS, Ofer Cassif, a member of the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, knew people killed by Hamas militants on Oct. 7. “One of them was a very dear close friend of mine,” Cassif told Sojourners. “She actually texted me from the security room minutes before she was killed with her husband.” Many progressive, anti-occupation Israeli peace activists lived in the region where Hamas killed more than 700 civilians in one day. Cassif, whose grandparents came to Israel from Poland in 1934 as part of the Zionist movement, is a secular Israeli Marxist and a leading voice against the war in Gaza. During the first Palestinian Intifada in 1987, Cassif refused Israeli military service in the Occupied Territories and was incarcerated in military prison. In 2019, he was elected to Israel’s parliament as the only Jewish member of the Arab-majority Hadash-Ta’al party. In January, Cassif publicly supported South Africa’s petition to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to investigate Israel for violation of the 1948 Genocide Convention in its war on Gaza. In February, some parliament members tried — unsuccessfully — to impeach him. For this interview I spoke with Cassif in late March over WhatsApp. It was nearly midnight in Israel. He was still sipping his yerba mate through a metal straw.

Do you hold Hamas responsible for the Oct. 7 attack? Yes. Obviously, I hold Hamas responsible. That’s not to say that the government of [Benjamin] Netanyahu is not responsible in some respects, too. But definitely the guilt, the blame, is on those who killed, on those who raped, on those who tortured, and torched. And those are Hamas’ people.

Why do you support the petition before the ICJ to investigate Israel for genocide in Gaza? I do not trust the Israeli government or Hamas or any other government to investigate itself. The ICJ is the authoritative branch to investigate allegations of genocide. Israel recognized its authority in 1949, when Israel became one of the first states to ratify the convention. The bottom line is to support the ICJ in calling on Israel to stop the war — to save lives, as simple as that. The more than 30,000 deaths in Gaza, most of them women and children, the disease and starvation, this is totally the blame of the government of Israel. And it should be stopped. Stopping the assault on Gaza is the only way to save the Israeli hostages. There’s no military way to release the hostages, only a political one — which necessitates ceasefire.

IN MARCH, CIVIL society groups across the Pacific — including churches — unveiled a landmark declaration to end fossil fuel expansion in the Pacific region. The Naiuli Declaration provides a moral rudder from Pacific communities to guide the international Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Pacific Islanders are championing the treaty as a legally binding mechanism to end new exploration and to support the rapid, equitable, and lasting phaseout of fossil fuels, core drivers of climate change and sea-level rise. To date, 12 nations have endorsed the treaty, including fossil fuel-producing countries Timor-Leste and Colombia. In the U.S., Maine, California, and Hawaii have also endorsed the treaty.

In envisioning our fossil free future, the Naiuli Declaration carries the twin aspects of vulnerability and resilience (the term Na i Uli draws from indigenous Fijian words for the steering oar in traditional double-hulled ocean canoes). There is the vulnerability of communities facing an existential crisis caused by climate change, putting at risk livelihoods, culture, our deep spiritual relationship with land and ocean, and the possibility for climate-induced displacement. The sense of exile evoked by this vulnerability resonates with the psalmist, who laments: “For there our captors asked of us songs, and our tormentors asked for mirth, saying, ‘Sing us one of the songs of Zion!’ How could we sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land?” (Psalm 137:3-4).

DESPITE WHAT DASHBOARD Jesus figurines might suggest, there is no plastic in the Bible. None. It’s a 100 percent plastic-free zone. Jesus does, however, promise eternal life. While Christians have a wide array of interpretations about what that means, we generally agree that Jesus did not mean through polyresins and microplastics, which have a nearly eternal life of their own.

Christians are on the forefront of the battle to reduce fossil fuel use and address climate change. We understand that God has given us a mandate to serve and protect the Earth and its communities. Churches have divested from fossil fuels. Christians have risked arrest for effective legislation. Youth are leading the global defense of our planet and people.

But, as the pressure to transition to renewable energy increases and fossil fuel demand drops, the CEOs of petrochemicals want to keep their money pipelines open.

Over the past 70 years, annual production of plastics has increased nearly 230-fold, reaching 460 million tons in 2019. China, with weak human rights and environmental regulations, is now the world’s largest plastics manufacturer, accounting for nearly one-third of global production. If trends in oil consumption and plastics production continue at the current rate, plastics will make up 20 percent of fossil fuel consumption by 2050.

Studies track with increasing accuracy the total mass of microplastics found in adults around the world. It’s a lot. You may as well just chew on your credit card. Microplastics are linked with a variety of human health issues, including reproductive disorders, organ damage, and developmental impacts on children.

FOLLOWING THE HAMAS attacks on Israel last October, President Biden drew a parallel to the Sept. 11 attacks on the United States. He remarked that in the aftermath of 9/11 “we felt enraged” and “we made mistakes.” The U.S. response in 2001 serves both as a cautionary tale to Israel and a reminder of the failures of the military-first approach the U.S. has taken to international terrorism.

After 9/11, the U.S. responded with war. This choice was just that — a policy choice. The U.S. could have used effective models of international policing to bring Osama bin Laden’s transnational criminal network to justice — and many countries stood ready to help. Instead, ex-President Bush chose a military strategy against nonstate actors. Thus began the Global War on Terror. This choice employed a war-based framework that permitted killing people suspected of terrorism as a first resort; allowed for indefinite military detention; and trained foreign forces to respond to threats of terrorism with lethal force. In 2023, according to the Costs of War Project, the U.S. was conducting militarized counterterrorism operations in 78 countries.

Twenty-three years of this approach has not defeated terrorist groups. Instead, these groups are more dispersed and recruitment has increased. This policy choice has resulted in up to 432,000 civilian deaths and cost U.S. taxpayers more than $8 trillion. The post-9/11 period has seen a fourfold increase in terrorist groups and terrorist attacks have increased fivefold per year globally. Part of this growth relates to the high numbers of civilian casualties caused by U.S. military operations, including drone strikes, which groups such as ISIS and al Qaeda exploit to bolster recruitment.

DEMOCRACIES OFTEN DIE by a thousand small cuts. The slide from a robust, if unfinished, democracy to an authoritarian government is incremental and uses inherent weaknesses in a country’s institution and culture. In the U.S., racism has been a core weakness debilitating progress toward a vibrant inclusive democracy, exploited by autocrats to maintain power no matter the cost to human dignity and freedom.

Since 2015, the U.S. democracy score has slid from 92 to 83, according to Freedom House’s global index, lower than any democracy in Western Europe. At a point when pro-democracy and anti-racism movements need to be strongest in the U.S., we find them at odds.

I work in many pro-democracy coalitions committed to political and ideological pluralism where it is challenging to identify the role of white supremacy and Christian nationalism in undermining democratic norms. Conservatives see these as “leftist” issues and moderates fear dividing an already fragile coalition. I also work with political progressives who often see police brutality and mass incarceration as aberrations in a functioning democracy rather than direct attacks on democracy itself, as political scientists Vesla M. Weaver and Gwen Prowse have laid out in their analysis of racial authoritarianism and as Black intellectuals and activists have understood for decades.

Authoritarianism is a system that concentrates wealth and power in a relatively small group of unaccountable people. Authoritarian systems are made up of authoritarian leaders and their institutional enablers, including members of political parties, media outlets, businesses, and religious institutions who provide autocrats with critical sources of social, political, economic, and financial power. Authoritarian systems engage in a range of anti-democratic behaviors to consolidate or expand power, such as weaponizing disinformation, gutting institutional checks on power, subverting free and fair elections, undermining civil liberties, and condoning political violence.

FOR MANY, TAX season is a scramble. Where are the receipts? How much do we owe? Why is it so complicated? But it’s also an annual opportunity to review our social contract, our shared moral obligation to fund the common good. The taxes we pay can affirm life, care for our elders, feed the hungry, house the poor, and care for creation. Taxes can also underwrite a bloated military budget that takes life and incentivizes war.

Until 2015, the largest segment of a typical tax bill did not support programs of social uplift for Americans, but instead supported the military-industrial complex and war. Over the last few years, however, there’s been a shift, even as military costs have continued to rise. That shift is due in part to expanded health care access — but also in part due to health care inflation. Now, providing affordable health care for those over 65 or on limited income through Medicare and Medicaid is the most significant portion

of your tax bill. Paying for war or supporting Americans at home are in a battle for top tax billing.

The average U.S. taxpayer contributes more than $13,000 each year in federal income taxes, according to our research at the National Priorities Project. That’s not a small chunk of change for anyone but the wealthiest among us. When we pool our funds, our federal income taxes are a powerful force, accounting for nearly half of federal revenue (much of the rest also comes from us, in the form of other payroll taxes).

Editor's note: As of Jan. 10, 2024, the Committee to Protect Journalists has documented at least 79 journalists and media workers killed in Israel, Gaza, and the West Bank since Oct. 7. This article will appear in the forthcoming February/March issue of Sojourners.

IN OCTOBER, NEARLY a week after the brutal Oct. 7 attack by Hamas militants on Israeli citizens, an Israeli military tank crew at the Israel-Lebanon border fired at a group clearly identified as press. Reuters’ journalist Issam Abdallah was killed, and six others were injured. Israel denied targeting the journalists.

While the Israeli government continues to say that the incident is under review, in December, human rights groups Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, along with wire services Reuters and Agence France-Presse, released the results of their own investigations into the Oct. 13 missile strike.

The journalists were reporting on skirmishes between Israeli forces and Hezbollah militants. They were wearing blue helmets and flak jackets, most marked “Press.” One of their vehicles had “TV” on the hood. They had been on a hilltop on the Lebanon side of the border for around an hour before the attack. An Israeli helicopter hovered above them for 40 minutes of that time. Their identity as members of the press — civilian journalists — should have been clear.

PROPHETS USE WORDS to encourage or condemn. The biblical prophet Micah’s command “to act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God” (6:8), for example, has rung in the ears of many. Language is a powerful tool for social change. However, some prophets don’t use words at all: They use their bodies.

Social prophets today that use their bodies often stand arm-in-arm in front of police barricades or walk miles for justice. But some prophets have used their bodies in another arena: athletics. And many of these prophets are women.

How many know the story of track and field star Eroseanna (“Rose”) Robinson? Some recall in 2016 when football quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem in protest of police brutality and in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. Few remember that in 1959, nearly 60 years before Kaepernick’s action, Rose Robinson refused to stand for the U.S. national anthem at the Pan American Games in Chicago because, to her, “the anthem and the flag represented war, injustice, and hypocrisy,” according to historian Amira Rose Davis. By refusing to stand, Robinson used her body to speak for justice.

But Robinson was a full-time activist on and off the field. Throughout the 1950s in Cleveland, she was a leader in the Congress of Racial Equality, an interracial group of students founded by the Fellowship of Reconciliation that paved the way for nonviolent actions in the U.S. civil rights movement.

POPE FRANCIS MADE history eight years ago when he became the first pope to publish an encyclical focused on the environment and our collective responsibility to end the poisoning of our planet. Unlike most such documents that stir debates largely confined to theological circles, “Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home” sparked a global reaction far beyond the Catholic Church.

In October, the pope again pulled our attention back to a worsening climate crisis and even more dire threats to our common home with the release of “Laudate Deum” (“Praise God”), which comes at a time when mounting evidence of more frequent climate emergencies has been met most often with apathy, not action.

“I have realized that our responses have not been adequate, while the world in which we live is collapsing and may be nearing the breaking point,” the pope writes. There are good reasons for the pope’s stark assessment. The burning of fossil fuels continues to reap obscene profits for oil executives while the impact of human-induced climate change, especially on impoverished nations, is devastating. Pope Francis laments that “the necessary transition towards clean energy sources such as wind and solar energy, and the abandonment of fossil fuels, is not progressing at the necessary speed.” The publication was timed for the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) taking place in November and December.

I’m particularly encouraged by the pope’s support for activists and grassroots organizers who have far outpaced most political leaders when it comes to mobilizing for climate justice. Francis endorses “a multilateralism ‘from below.’” While right-wing demagogues who fancy themselves populists exploit fears of cultural displacement and economic anxiety, the pope’s hopeful populism is rooted in standing in solidarity with the poor, bringing people together across divides, and challenging structures of injustice that prop up immoral syst

I'M TIRED OF hearing politicians use “family values” as shorthand for a narrow and often misguided agenda. It is time to broaden and reclaim a truly pro-family agenda to protect and strengthen all families. Since at least the 1990s, the political and Religious Right have often claimed a monopoly on “family values.” Many Democrats have only exacerbated this trend with their reticence to frame their policies as pro-family. As a result, whenever we hear a politician talking about “family values” or “pro-family policies,” it’s shorthand for policies that restrict women’s autonomy or threaten LGBTQ+ rights.

Of course, outside of the world of politics, it’s obvious that people with widely divergent perspectives view the welfare of their family — whether biological, blended, or chosen — as the center of their lives. Protecting families should be a nonpartisan issue with bipartisan support, not another casualty of partisan extremism.

What would a holistic pro-family policy agenda require? As Christians, we have a responsibility for both the pastoral and political welfare of families. It is these intimate, human, familial relationships that generate our common good. True family values in politics should mean programs and policies that protect human dignity, help families thrive, and promote space for kids to grow and learn. As Christians, we stand for this kind of “family values” not to force our theological beliefs on others, but to stay faithful to scripture’s commands to love God and generously provide for our neighbors’ flourishing, protecting the most vulnerable regardless of whether they share our beliefs (see Matthew 22:36-40).