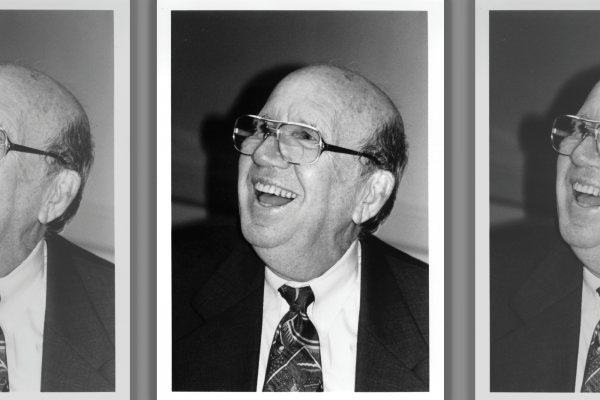

IT FEELS AS though the United States could not become more polarized. Across our contemporary chasm, no matter what side people believe they occupy, the other always feels unreachable. That’s why this is a particularly apt time to ponder the late Rev. Will D. Campbell, who was born 100 years ago this July.

A white Mississippian raised in a 1920s Jim Crow thicket, Campbell rejected that era’s rampant racism early on. When the civil rights movement began, he embraced its goals with open arms. Campbell’s no-frills reading of the Sermon on the Mount led him to the cause. When 16-year-old Ernest Green and eight other African American students entered Arkansas’ Central High School in 1957, Campbell walked beside them. When the Southern Christian Leadership Conference came together, Campbell was the only white man in attendance. When the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee formed in 1960, Campbell made the first cash donation. To the brave leadership from the Black community, he added his own. For everyone involved, it was an extremely dangerous endeavor.

Then, at the midway point in Campbell’s life, his ministry underwent a drastic change. He set a controversial new direction for himself, one that confused many of his supporters and angered others. He began a soul-saving outreach to the white racists of the local Ku Klux Klan.

“Anyone who is not as concerned with the immortal soul of the dispossessor as he is with the suffering of the dispossessed is being something less than Christian,” Campbell wrote in his 1977 book, Brother to a Dragonfly.

The type of social justice Campbell had been pursuing before this, noble as it was, amounted to a circular firing squad of humanity, he realized. The course correction he made offers a window into a way to navigate America’s current predicament.

Campbell came into a new understanding of Christian social justice through a conversation with an agnostic-leaning pagan named P.D. East. A Mississippi native who grew up in poverty, East owned the Petal Paper, a tiny weekly newspaper founded in 1953. Initially more profit-minded businessman than crusading journalist, East started his one-man paper with the intention of avoiding controversy to keep advertisers happy.

Six months after the first edition, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its Brown v. Board of Education ruling, making segregated public schools unconstitutional. Unlike Campbell, East had never questioned the white supremacy-based segregation in which he grew up. But after the court’s ruling, as whites clamored to avoid integration, East came to feel they were denying African Americans the promises of the U.S. Constitution, and he found hypocrisy in their actions. Soon East’s little Petal Paper began relentlessly attacking white racists with a kind of satire the literary critic Maxwell Geismar described as a “native brand of country humor straight out or descended from Mark Twain.” East’s unique stand — made from deep within Mississippi by a native white son — soon had paper subscriptions skyrocketing. Supporters included Eleanor Roosevelt, Upton Sinclair, and Martin Luther King Jr.

Locals, though, abandoned the paper. East began to receive anonymous threatening phone calls. In 1963, he fled Mississippi fearing for his life. He settled in Fairhope, Ala., where he continued producing the Petal Paper and mailing it to subscribers across the country.

Campbell visited East in Fairhope in 1965. Their friendship had started a decade earlier, around the time Campbell quit as chaplain at the University of Mississippi because his views on race clashed with those of the administration. Campbell and East came to have common thoughts on racial equality, but on the topic of religion they remained miles apart. Campbell, raised Baptist, preached his first sermon at 17 and never wavered in his faith. East, raised Methodist, rejected organized religion by his mid-30s. He enjoyed ribbing Campbell about his religion. East once asked Campbell to sum up Christianity in 10 words or less. “We’re all bastards but God loves us anyway,” he answered.

Campbell’s visit to Fairhope in August coincided with the murder of Jonathan Daniels, a white civil rights supporter shot to death by Thomas Coleman, an Alabama deputy sheriff. Campbell knew Daniels, an Episcopal seminarian. When the news came across East’s television, Campbell launched into an angry diatribe about “rednecks,” “crackers” and “Kluxers” who he said held no respect for the law. Something about the situation reminded East of Campbell’s condensed definition of Christianity, and he asked Campbell if Jonathan Daniels had been a “bastard.”

When Campbell ignored him, East raised his voice and repeated the question. “Yes,” Campbell said. East then asked the same of Thomas Coleman and Campbell said, “Yes.” Then East asked: “Which one of these two bastards do you think God loves the most?”

Years later, Campbell recalled how the question sent him across the room to stare out a window at a streetlight. He was 41. In that moment he realized he’d spent 20 years engaged in a “ministry of liberal sophistication,” he said, one that operated beneath “the banner and umbrella of social science and legislation, Caesar and politics.”

He’d been brought to a vantage point that made him see Daniels and Coleman as equal children of God — and he suddenly viewed the entire race situation as a tragedy. “One who understands the nature of tragedy can never take sides,” he said. “And I had taken sides.”

From 1965 forward Campbell remained committed to social justice — maybe even more so. But now it was a commitment to people, not the causes they espoused or the reasons they espoused them. While Campbell continued unqualified support for civil rights and equality, he also established genuine friendships with KKK members and other racists, visiting them in prison, presiding over their weddings and funerals, and welcoming them into his home near Nashville.

The clearest illustration of Campbell’s new understanding of his faith and social justice occurred in 1998, when he attended the trial of Sam Bowers Jr., a co-founder of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan accused of ordering the 1966 murder of Vernon Dahmer Sr., president of the Forrest County chapter of the NAACP in Mississippi. The first thing Campbell did when he walked into the courtroom was shake Bowers’ hand. Then he embraced members of Dahmer’s family. A reporter asked how he could do both. “It’s because I’m a goddamn Christian,” Campbell said.

I’m not sure whether the country’s current polarization is a result of a tragedy. But I am sure the result will be tragic if we let resentments, accusations, and assumptions continue to separate us. The Rev. Will D. Campbell is gone — he died in 2013 — but his example, and the gospel he believed in, remain.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!