This interview is part of The Reconstruct, a weekly newsletter from Sojourners. In a world where so much needs to change, Mitchell Atencio and Josiah R. Daniels interview people who have faith in a new future and are working toward repair. Subscribe here.

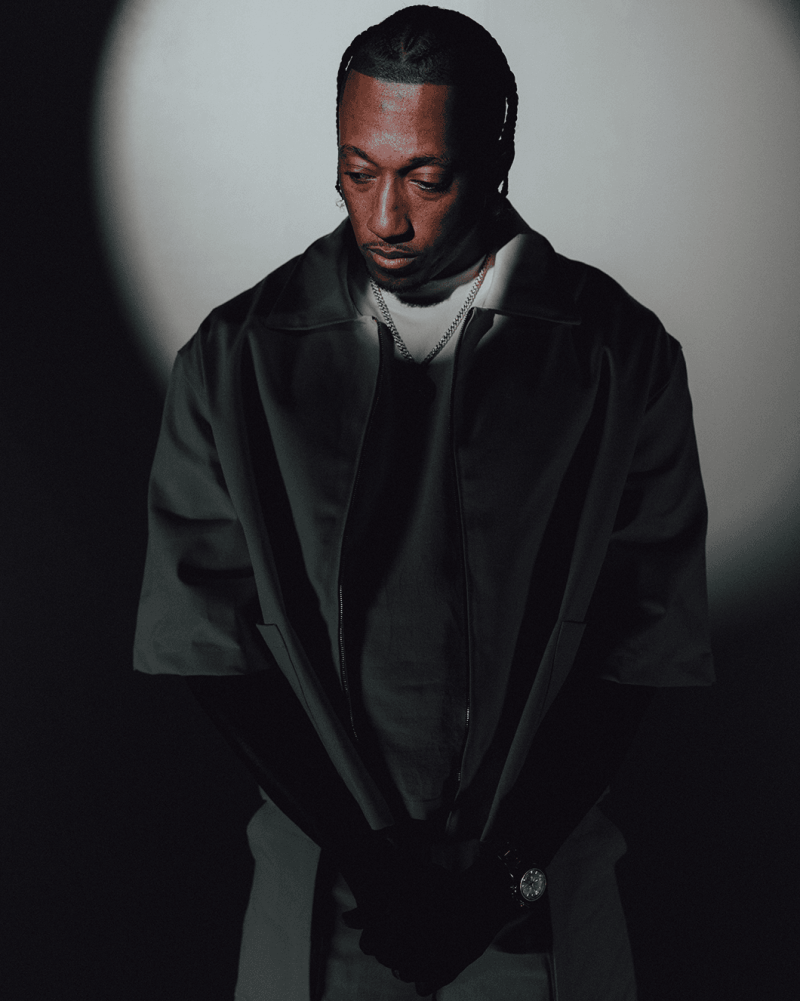

For as long as Lecrae has been a public figure, he has been a lightning rod for white evangelical racism.

A spearhead for the movement that turned Christian hip-hop from a misfit genre to a powerhouse industry, Lecrae has consistently endured racism thinly veiled as theological critique. While he was earning deep respect from hip-hop luminaries—Sway In the Morning and Kendrick Lamar, for example—he was fighting a Christian industry that only begrudgingly came to accept that CHH was here to stay.

Early on, critics claimed “Christian” and “hip-hop” were contradictory terms, and Christian rappers like Lecrae were putting godly messages second to godless culture. Then, as the U.S. began another reckoning with racist police violence, Lecrae was accused of division, partisanship, and putting “political issues” like racism before “biblical issues” like abortion. When he attempted dialogue, white pastors told him to his face that chattel slavery was a “white blessing.”

I was a teenager at the beginning of this period, from 2014-16. I watched as other white Christians berated and harassed Lecrae to no end. Though I was a proud conservative, I couldn’t believe what I was witnessing. I began to see clearly that my community was not just shaped by abstract political commitments, but also by historic bigotries. Digging through those bigotries led me to investigate systemic injustices. When I trace what led me to become the leftist I am today, I often start with Lecrae’s boldness, his willingness to tell the truth at great sacrifice.

Behind the scenes, however, he almost left it all.

In his own words, he deconstructed his faith after receiving backlash for speaking out against police violence and racism after the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and more. More than that, he suffered from serious depression, doubt, and substance misuse. On the other side, Lecrae came to reconstruct his faith away from “Western Christianity.”

But as I’ve listened to him narrate this journey—on his podcast The Deep End With Lecrae, on his public platforms, and on his new album Reconstruction—it’s become less clear to me what “deconstruction” and “reconstruction” tangibly mean to Lecrae. At times it seems he’s embracing a very conservative definition of the terms.

Take, for example, his 2022 thread on X, then-known as Twitter.

“There are 2 types of deconstruction happening in the church. One is healthy the other is dangerous,” he wrote. He criticized many millennials who he claimed were letting "culture [take] precedence over scripture."

These were the very phrases once weaponized against him when he questioned evangelical racism. Why would he use them now to describe others?

On his podcast, he hosts multiple “ex-LGBTQ+” Christians, but never a queer Christian who affirms same-sex marriages. On Instagram, in a now-deleted comment, a follower asked Lecrae to speak about the genocide in Gaza. “You have 900 followers,” Lecrae, who has 2.4 million followers, wrote. “[W]hat if YOU posted to them the issues that YOU felt were pressing.”

READ MORE: Palestinian Christians Have a Warning for the American Church

Had Lecrae’s reconstruction led him to a defensive and aggressive stance toward those asking him to rethink conservative sexual ethics or speak out on behalf of Palestinians?

On Oct. 5, Lecrae’s worldwide tour stopped in Chicago, and we sat together for an interview. My interview was sandwiched between another press obligation and his VIP meet-and-greet, but Lecrae engaged each of my questions seriously. We discussed what he would have said to the deconstructing Lecrae who doubted God’s existence, how his theological beliefs have actually changed, Christian support for Israel’s genocide in Gaza, and more.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Mitchell Atencio, Sojourners: My understanding of the timeline is that your deconstruction was between 2015 and 2020. Is that about right?

Lecrae: I would say 2015-2018.

Did you know that you were going through a deconstruction? Did you call it that at the time?

I didn’t have that language. I didn’t have the language of “deconstruction.” I remember texting my friends, “I don’t believe this is true anymore.” They said, “Yes you do!” But I was in a very, very confused and dark place, like, “I don’t think I believe this.” I was wrestling with it all.

When you look back now, do you understand that deconstruction as something that was a dangerous place for you or a healthy and necessary part of your faith walk?

What many millennials refer to as deconstruction is them saying, “I’m abandoning organized religion, Christianity, all together. I’m finding a new way of living outside of this.” I would say that’s unhealthy, because when you step away from Christ, as a believer, now you’re looking for something to hang your hat on—some source of reality or truth or what not.

But I do think there can be a healthy deconstruction. Jesus did it all the time. He would say, “You’ve heard it said … but I say.” Right? “Let me take down what you’ve believed forever and let me give you something different.”

That was healthy for me. My views of what church was, my views of what God wanted, were more cultural than biblical.

When I read your book I Am Restored, it didn’t always seem clear that you knew you were going to hold on to Jesus.

Right, that’s right.

So, what would the Lecrae at the beginning of his deconstruction have said to what you’re saying now about healthy versus unhealthy deconstruction?

“You’re still trapped. You still are hypnotized by this Western, cultural faith. I’ve been doing this a long time. I’ve been to churches. I’ve read the Bible. I’ve been to Bible institutes. You’re just wrong.” That’s probably what I would have said to me now.

And what does today Lecrae say back?

I hear you. And I raise you this challenge: Have you really dug into the Christian faith outside of a Western, American context? When’s the last time you went to a Korean church? When’s the last time you went to a Somali church? Do you know anything about the Christian history in Turkey or Ethiopia? Or is everything you’ve gotten just very Westernized. If you can’t say “yes” to those, then you’ve only explored a smidgen of this Christian faith.

When you did that exploring, what sort of beliefs changed for you? What did you believe then that you don’t now?

What I believed then was that the Western world had the monopoly on theology, what it meant to understand God, what it means to know the Bible. Our aptitude was the highest; we were the most adept to really understand this.

What I had to learn is that we have just commandeered the narrative. Whoever burns all the other books controls the story. What I learned is that we don’t know it all. Not to downplay the Western world or America—I love America!—but, if we’re on a baseball field, we’re watching from the dugout. We’re not outfield, we’re not centerfield, we’re not seeing things from the pitcher’s mound. We think that, because we see from the dugout, we understand the whole game. When in fact, there’s other vantage points that we don’t see.

What theologically, specifically, changed? Are you in a different church tradition or?

OK, just to give you an example: We don’t really look at things from an ancient, Near Eastern perspective. So, the way Jesus was trying to articulate things, we tend to not see that. A very simple one: When you read Psalm 23 and it says, “He leads me to green pastures,” instantly your brain is thinking of pastures that you’ve seen. Because we have this Western lens, we’re thinking cow pastures, greenery. That is not at all what David was trying to communicate in Psalm 23. If you go to Israel, what tends to happen is the dew rolls down these cliff rocks, and a small little patch of grass pops up here and there. That would be what he would call a green pasture.

What he’s really articulating is, “You’re not gonna see the whole pasture feed you. You’re gonna get a little tuft of grass here, and that may last you a day or two. Then you gotta pray God leads you to the next one.”

Another one, very simple, and this is controversial for a lot of people, but someone getting up, doing an oratory in front of a crowd, with music, on Sunday morning, is what we call “church.” We say that is a mandatory thing. But it’s not mandatory. It’s something that we do, but when it says in Hebrews, “Do not forsake the fellowship,” we’re not talking about this Sunday gathering. We’re talking about connectivity with other believers who are a part of your community. That’s the thing I didn’t understand.

So, you feel less pressure to be there every single Sunday morning with the same body? Or what do you mean when you say that?

Yeah. I feel like I need a group of elders. But if we looked at what Paul in Corinth was doing, it would look vastly different than what we have going on every Sunday.

That’s not to say what we have going on is something God disapproves of. It’s just to say that me missing this Sunday is not what Hebrews is talking about. Me missing walking into a building, with people I don’t know, that I don’t connect with, that I see for an hour, is not at all what Paul—or, the author of Hebrews—is intending. What he was intending was, “Who are the people that you’re connected to consistently? Fellowship with them consistently, throughout the week!”

Did your reconstruction change how you approach politics?

Oh absolutely.

How so?

The American narrative is very empirical [sic]; it’s empire driven. Empire, it’s about expansion, control, and domination. You’d be remiss to say that’s not what, in many ways, politics aims to do. “Hey, we need more control so we can do this or change this or change this.”

Oftentimes, they’ll coopt Christianity to get those things done. “We need to vote this way,” because there’s an aspect of our faith, feeding the homeless—“The only way we’re gonna feed the homeless is if we vote this way.”

Or, “We have views on marriage, the only way that’s gonna be right is if we vote this way.”

251008-LecraeEmbed.png

Christianity has always been about the kingdom, not the empire. You don’t see Jesus giving a mandate to change the nation. You do see Jesus giving a mandate for his church and how we should look within the nation. Jeremiah does tell us to seek the welfare of the city, but he’s telling that to a group of exiles, captives. He’s not saying takeover the city. He’s saying seek the peace of it, bless them.

For me, now I try to be more kingdom oriented. The politics are a means to an end.

How does that play out in terms of what you feel comfortable speaking to from your platform? This is part of my story, I grew up listening to Lecrae and Dream Junkies and Propaganda and other folks. Y’all were a big part of getting me to step outside the white church lens when I thought about police violence or racism.

My growing up was really impacted by you speaking out on those things. I wonder if you look back at 2012, 2014 and think you were speaking out in ways that were good and would like to mirror today.

I would temper it. Because I believed, in 2016, that the way to get things to change was by force—

Violence?

Not necessarily violence, but aggression. Not love, aggression. “This is wrong! Change it now!” When I look back at William Wilberforce, when he was trying to affect slavery, when I look at the Civil Rights era, it wasn’t that. [Aggression] wasn’t what made the change happen. It was actually walking in love.

You don’t think Civil Rights era folks spoke really strongly?

Don’t hear me say they didn’t speak strongly, but they were defined by love. It doesn’t mean you temper the truth, but it means, “Do I really want you to change? Or do I want to shame you with my words? Do I want you to feel the shame, or do I want you to hear my vantage point?”

One of the most beautiful things I can reference—I’m gonna mess this story up—but essentially the story is that a slave girl was treated so poorly, and after slavery ended, she did not retaliate or wish ill will on the people who did her wrong. Matter fact, she wanted the best for their children, and in some kind of way she served their children, and it blew the mind of the former slave owner. Because he was like, “Why would she do that?” And I think that’s the story of the Good Samaritan. That’s the story of Jesus talking to the Samaritan woman—“What? Why are you talking to me? We don’t agree! We don’t see things the same!” And Jesus says, “I’ve got something for you.”

Now, when it comes to speaking to other Christians, Jesus gives us permission to speak pretty harshly. He’s turning tables over in the temple. When we’re cleaning house, we turn some tables over. But to the outside world who does not see things from our worldview, we have to be tempered in love. They’ve gotta see something peculiar about us.

What are some of the things you feel like speaking to other Christians about right now?

My lord. The list goes on and on.

You mentioned going to Israel. I wonder how you’re feeling now, as someone who has visited Israel, about what’s happening in Gaza.

[Pause]

Christians are [pause] so narrow visioned. Specifically evangelical Christians. The evangelical gospel in and of itself is problematic. Because it is based on individual salvation. It is based on just getting to the other side. Because of that, there’s a high view of orthodoxy, high view of orthopraxy, and zero view of orthopathy—there’s no empathy for complex, nuanced narratives.

A gospel that focuses on individual salvation was not what Jesus was preaching. “The Kingdom of God is at hand.” Well, the kingdom asks us to push forward a different agenda, one of love, joy, peace, kindness, gentleness, self-control, and goodness. How can you support senseless murder and violence, on any continent from any country, unless you only care about your individual salvation? That’s not kingdom.

So, when I think of Gaza and Israel, for me, what I see is a very complex and nuanced situation that you’re a fool if you think you can just say, “Well, this is God’s team, so I’m only on this team.”

Let me ask you about something specific then, because I understand the overall situation might be complex: Do you think Christians should support sending military arms to Israel?

No. I don’t.

The reason I don’t is because I think we’ve entangled the nation-state of Israel as biblical Israel, which it’s not. They’re not the same. We can call anything Israel! We can draw some lines and create boundaries and say, “This is Israel.” But Israel was always a people, never a nation-state, in the scriptures. So you don’t have a justification for “This is God’s land.”

There’s much to be said about who the nation of Israel is. Because you’ve got the Mizrahi Jews, the Sephardic Jews, the Ethiopian Jews. That’s a whole other conversation. But you can’t say you’re just supporting God’s people.

Then you’ve got folks saying, “Well, they [Palestinians] are Islamic.” I’m just wondering how that is justification. Is Islam anti-American? That’s what some people believe, but I’m like, “You know America’s not a Christian nation.” That’s a whole other conversation. The founding fathers were probably deists, but they weren’t Christians if you do your digging.

So, no, I would not support that.

On your most recent podcast, I was struck by what felt like the third or fourth time in my research I came across you talking about demons and demonic forces. I don’t remember hearing you talk about that much before. Is that something new for you?

Absolutely.

What caused that?

Well, one, the reconstructing. I had to tear down some of these dogmatic perspectives. I wanted to hear people think critically and intellectually about the unseen realm. So I began to do some research, reading books from Michael S. Heiser and different people.

Why is it that intellectual Christians can believe in a salvation and God, an existential experience with Jesus, but we can’t believe in demons? I felt hypocritical. I had to say, “Alright, Lord, I’m open. I’m not hunting it, but I’m open.”

Once I began to be open, it was clear. It was everywhere I looked. You can see the principalities and dark powers at work, behind the scenes. Then, every so often, God may remove the veil and say, “Look at this!” And I can’t believe I just saw that. That started happening more and more.

What do you think is the mark of a reconstruction gone well?

When the foundation is Christ, if you’ve kept him as your foundation, you can build from there. Many people have constructed religious traditions and a faith that is a house with no door: No one can get in, and no one can get out. If you are OK with fluidity—people are scared of that fluidity—my foundation is firm; I stand on Jesus. My thoughts on certain theological vantage points may change, but that’s OK. If I have a different vantage point on a particular view today, and it changes tomorrow, I want people to be OK with that. It’s not dangerous.

Thanks for the time. I appreciate it.

I appreciate your questions! Very, like [pause]. You got me saying stuff I’ve never said!

Is that hard?

It’s just. I mean. People don’t like nuance. So when you say something like, “Should Christians go to Israel?” And I say, “No.” They’re gonna [imitates critics], “Ahh!! Oh my God! Oh my God!” And it’s like—bro, you’re not gonna wrestle with my yes on that. You’re just gonna [pauses]. But it’s all good. I appreciate you, man.

Does Lecrae think Christians should support sending arms to Israel? “No. I don’t. The reason I don’t is because I think we’ve entangled the nation-state of Israel as biblical Israel, which it’s not.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!