Review

OVER THE PAST 2,000 years, Christians have found myriad ways to divide the body of Christ. We are now more divided than ever, with more than 40,000 Christian denominations worldwide. Perhaps, in this context, we are asking the wrong questions. Do we really understand God’s desire for the church to be one? Do we as individuals have a yearning for the unification of the body of Christ? Why do we create the divisions we create? Why do we maintain the divisions that already exist? How can we break through these barriers to heal a broken church?

Christena Cleveland sets out to answer all of these questions and more in her latest book, Disunity in Christ. Cleveland is a young, energetic, and brilliant teacher, speaker, and researcher in the fields of social psychology and faith and reconciliation. For those concerned with reconciliation in the church, which should be all of us, hers is a voice to take seriously.

In Disunity, Cleveland quickly breaks the ice by poking fun at herself and by pointing to her own personal prejudices and biases that have led to her categorically labeling fellow brothers and sisters in Christ as either a “right Christian” or “wrong Christian.” The reader is immediately able to connect with her and realize the ways in which we have created division in our own lives, whether because of race, gender, orientation, education, location, socio-economic status, theology, or political affiliation. It also becomes apparent why we prefer our homogenous groups.

THERE ARE apparently 2,000 film festivals around the world, so the format of red carpet arrivals, gala screenings, and Q&A sessions that appear all but scripted in advance have become well and truly entrenched. The best festivals recognize that their purpose is to cast a spell over filmgoers and filmmakers alike, inviting them into a spacious place where the heart of the dream that led to the film being made and the audience’s reason for watching it can beat in a community of people who thirst for art that gives life. Unsurprisingly, the biggest festivals find it hardest to pull this off—asking for contemplative mutuality at Cannes or Sundance is like looking for a Buddhist tea garden at Disney World.

Yet film festivals can be places where small is indeed beautiful. It’s only the movies that need to be big—or at least their capacity to alchemize with the viewer’s autobiographical narrative. The trappings of VIP lounges, paparazzi, and celebrity gossip are just that: They trap the aesthetic air, creating distance between people and art. Smaller festivals may be more capable of nurturing something that really feels like community.

So when at North Carolina’s Full Frame Documentary Film Festival this spring we watched Visitors, Godfrey Reggio’s follow-up to his epochal Qatsi trilogy, and the diverse faces of human beings segued into natural landscape and a Louisiana cemetery, the sense of empathic connection with an artist who spent the first 14 years of his life in New Orleans and the next 14 as a Christian Brothers monk was palpable. The impossible-to-categorize musician Nick Cave portrayed a sly version of himself in the pseudo-documentary 20,000 Days on Earth, intercutting concert footage with a role-played therapy session, visits with friends, and a neo-noir road trip, to moving effect. And the gay rights courtroom drama of The Case Against 8 played to an audience of citizens whose state had adopted a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage; the showing led to near-euphoric anticipation of how a better history can reverse this tide.

MUSIC IS OFTEN regarded and consumed as something that fills a space—the chords of an organ resounding off the walls of a sanctuary, the beats of a drum circle riding on the breeze through a park, the harmonies of an orchestra flowing from my headphones into my ears as I write. Music even transcends physical spaces to permeate the heart and the soul with emotion.

In Music as Prayer, pastor and musician Thomas H. Troeger invites the reader to cherish and engage in music as an act of prayer. Taking into account the metaphorical, scientific, and practical aspects of music-making, Troeger illustrates the power of music to not only fill a space but to also clear a way for meaning and creativity. Building upon Henry Ward Beecher’s metaphor of a boat stuck on the shore, Troeger describes how the “mighty ocean-tone” of a church organ brings the “tide” needed to lift up the members of the congregation and set them free from the shore.

In what Troeger calls a “dialogic process,” music lends rich metaphors to language and changes the effect of language upon the listener. The same song played in two distinct styles can convey two completely different sets of emotions.

From the ancient flute invented 35,000 years ago to today’s smartphone streaming songs on demand, music has occupied a central part of the human story. The mystery of music lies in the way that sound waves can blend into melodies that speak directly to the human yearning for wholeness. Creating space for both celebration and lament, music has the capacity to hold opposing emotions in the same breath. Music can provide release from suppressed inner tension and give voice to even the most unspeakable emotions.

CLIMATE CHANGE and its accompanying issues are mammoth topics. David Tracey’s The Earth Manifesto and Michael S. Northcott’s A Political Theology of Climate Change are ambitious and sound theoretical and practical treatments.

With different faith backgrounds, each brings to the task the urgency of the moment. Tracey is a Vancouver urban ecologist, a fiction and nonfiction writer, a writing teacher, and an avid housing co-op dweller with his wife and two school-age children. He has spearheaded several community garden co-ops. Northcott is a priest in the Church of England and a University of Edinburgh social ethicist who has written on understanding space and its sacred sharing, urban ministry and theology, and now this, his third book on climate change.

Tracey’s The Earth Manifesto dives right into the ecological mandates of our time and place. It gently and consistently employs an implicit Buddhist perspective to offer concise chapters—really a set of tools—to name, address, engage, and sustain a meaningful citizens’ involvement. These are expressed in two parts: three big ideas and three big steps. The ideas consist of “Nature Is Here,” “Wilderness Is Within,” and “Cities Are Alive.” Tracey’s three big steps are “groundtruthing”—engaging deeply in a place to shape one’s environmental efforts; political advocacy; and building a community to help spread a campaign for change.

Two concepts stand out vividly. Tracey’s explanation of groundtruthing conveys the need to test a theoretical perspective by getting right on the ground to verify its potential in the concrete. One intuits incarnational theology here. He also affirms the nature of engagement from its French origins to mean “someone passionately committed to a cause”: pledged, dedicated, or devoted. For me this summons the discipline of spirituality in the service of social justice.

THE CLASSIC COMIC book hero is given a post-WikiLeaks spin in the film Captain America: The Winter Soldier. He realizes that he is being asked to participate in the extrajudicial killing of people whom a magic formula has decided might threaten the established order in the future. It’s intriguing that even Nick Fury, one of Captain America’s “bosses” at the superhero super-agency S.H.I.E.L.D. (lines of authority are never particularly clear when super powers are in play), almost goes along with this.

To build a new world, sometimes you have to tear the old one down, says character Alexander Pierce, played by Robert Redford in a role that both echoes and inverts the ones he often took in the ’70s—where, in films such as All the President’s Men and Three Days of the Condor, he fought the system from within for good. This time Redford’s having fun as a bad guy, while Captain America (aka Steve Rogers) is the golden boy flirting with the audience and inviting us into his subversive politics (indeed the first words he speaks—the first words of the movie—are “on your left”).

So The Winter Soldier is striving for far more than your typical comic book movie and has been clearly influenced by the Dark Knighttrilogy in aiming for philosophical depth. There are interesting ideas here—S.H.I.E.L.D. being part of the problem and the character Winter Soldier’s name evoking the 1972 documentary Winter Soldier about Vietnam vets expressing regret. There are fun bits of business with Steve Rogers’ difficulties in adjusting to the contemporary world (such as the dawning reality that Star Wars andStar Trek are different things). And there’s real character development, especially in Rogers’ interactions with the Black Widow.

Everyday Saints

St. Peter’s B-List: Contemporary Poems Inspired by the Saints, edited by Mary Ann B. Miller, is not a collection of sentimental greeting-card-style verses; instead these literary works wrestle deeply with the human condition and the yearning for holiness, sometimes implicit, sometimes explicit. Ave Maria Press

City Missions

For nearly 30 years the Christian Community Development Association has been a resource for people seeking to do prophetic, non-paternalistic urban ministry. In Making Neighborhoods Whole: A Handbook for Christian Community Development, CCDA co-founders Wayne Gordon and John Perkins, and other veteran and emerging leaders, revisit key principles and lessons learned. IVP Books

IT IS FITTING that The Collected Poems of Denise Levertov (New Directions) begins with “Listening to Distant Guns,” written in 1940, when the poet was just 17: “The low pulsation in the east is war.”

The subject of war and its horrors, a constant in Levertov’s poetry and in her life, surfaces for the final time at the very end of this big book with these lines, written in 1997, from the poem “Thinking About Paul Celan”: You / at last could endure / no more. But we / live and live, / blithe in a world / where children kill children.

Denise Levertov (1923-1997), an American poet born in Ilford, England, to a Christian-Jewish father who was a descendant of Rabbi Schneur Zalman, founder of Chabad Hasidism, and a Welsh-Christian mother, herself the descendant of the Christian mystic Angell Jones of Mold, began to see her spiritual sensibility take a more formal religious shape only in her late 50s, when she opened to the liturgical, mystical, and social justice dimensions of Christianity, especially Catholicism, to which she later converted.

Two recent biographies, Dana Greene’s Denise Levertov: A Poet’s Lifeand Donna Krolik Hollenberg’s A Poet’s Revolution: The Life of Denise Levertov, explore deeply, albeit with inevitable overlap, the serial passions and enduring poetics of this singular artist.

At age 11, both biographers tell us, Levertov was going door to door peddling The Daily Worker in Ilford. At 12, she sent a batch of her poems to T.S. Eliot, and received back from him an encouraging response.

Poetry was her life’s purest passion. She had many lovers, many headlong, hurtful affairs to compensate for her romantically derailed and failed marriage to writer-activist Mitch Goodman. She also had a troubled relationship with their son, Nikolai, to whom Collected Poems is dedicated.

AS THE U.S. mobilized for World War I, a wave of patriotic fervor and xenophobia swept the country. Anything German was suspect, and those who were German-speaking and refused to fight against Germany were doubly suspect. Resentment and anger were directed at Anabaptist groups; several churches were burned and pastors beaten.

Inevitably, the demands of the state conflicted with the rights of conscience. Christian pacifists who only desired to be true to their beliefs by not serving in the military faced a militarized state that saw them as disloyal and disobedient. There was no legally recognized right to conscientious objection—if drafted, the only alternative for objectors was to go into the military and then refuse to participate.

Hutterite leaders had agreed that their young men would register, but if drafted and required to report for military service, their cooperation would end. They would refuse any orders making them complicit in war. Pacifists in Chains is the story of four young men—David, Michael, and Joseph Hofer, and Jacob Wipf—from the Hutterite colony in Alexandria, S.D., who faced that choice. Duane C.S. Stoltzfus, a professor at Goshen College in Indiana, was given access to previously unpublished letters from these men to their wives and families; the book is built around those letters.

Upon being drafted, the four reported in May 1918 and were sent to Fort Lewis, Wash. When they arrived, they immediately faced the test. Ordered to sign an “enlistment and assignment card” and line up as soldiers, they refused and were taken to the guardhouse. Following a brief court-martial, they were found guilty and sentenced to 20 years. Two weeks later, they were in chains and with armed guards on a train headed south to Alcatraz prison in the San Francisco Bay, then a military “disciplinary barracks.” Once there, they again refused to put on the uniform—in this case a military prison one—and were placed in solitary confinement in “the hole,” a basement dungeon. The cells seeped water and were infested with rats; the men were given bread and water to eat and subjected to beatings.

The Spirit’s Work

Just Jesus: My Struggle to Become Human, by Walter Wink with Steven Berry, is the final book by the late, influential Christian thinker. It blends brief autobiographical vignettes with essays on key themes in Wink’s work, offering insights into how his life story shaped his faith, thought, and witness. Image

Border Truths

On “Strangers No Longer”: Perspectives on the Historic U.S.-Mexican Catholic Bishops’ Pastoral Letter on Migration is a collection of essays by scholars and policy experts that uses the 2003 pastoral letter on immigration “Strangers No Longer: Together on the Journey of Hope” as its starting point. Paulist Press

THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Radical Jesus, edited by Paul Buhle, has three distinct sections offering different expressions of Jesus’ life and social message. The brevity of the graphic novel medium allows the writers to construct a clear and distinct message in a moving art form.

Part one, “Radical Gospel,” illustrated by Sabrina Jones, uses biblical quotes to construct a visual story that connects the words of Jesus to modern situations. The black and white ink styling is simple yet profound.

While Jesus and his disciples are portrayed as first century Jews, the people Jesus interacts with and tells parables about are all in modern dress. This puts Jesus in an accessible conversation not only with his disciples, but also with the reader. In a collection of Jesus’ sayings from the Sermon on the Mount, the art drives home the emotional impact of his words.

Jones does not shy away from the radical implications of Jesus’ message. My favorite of her modern interpretations is an image of the destruction wreaked by the 9/11 attacks, contrasted with Jesus’ reference to the temple in Jerusalem, where he exclaims, “The day will come when there isn’t one stone left on top of another that is not thrown down.”

ONE YEAR MY small group decided to have each member choose a person named or alluded to in the gospels to “follow” during Lent. We researched our people and the customs of that time and reflected individually and collectively on their encounters with Jesus. Then we hosted a community meal for family and friends on the night before Easter. Each member of our group came in character as the person we’d studied and tried to recreate the mood of that frightening, confusing, grief-filled night for followers of Jesus after his death and before his resurrection. After the meal, each of us presented a monologue that tried to project what our person might have been thinking and experiencing at that time.

The attempt to immerse mind, soul, and body into scriptures that I had listened to for much of my life (but perhaps hadn’t really heard) was a transformative experience: It burned away long-held assumptions and revealed new facets of chapter and verse.

The book Creating a Scene in Corinth: A Simulation, by Sojourners contributing editor Reta Halteman Finger and George D. McClain, provides a useful and fun toolbox for small groups, Sunday schools, religion classes, and even imaginative individuals who want their own full-immersion experience of scripture and biblical scholarship. It invites readers to a deeper understanding of the apostle Paul’s letter to the church in Corinth by using role play to “become” members of the different factions of that community as they hear Paul’s words read for the first time. The authors assert that “as we more clearly experience what Paul meant in the first century, we can better understand what his writings mean in our 21st century context.”

THE STILL, ATTENTIVE, affectionate, at times lamenting, always sagacious, well-defined, occasional poems in This Day, Wendell Berry’s most recent collection, are a magnificent gift to American letters.

For nearly 35 years Berry has kept the Sabbath holy. His practice is either unorthodox or so deeply orthodox that professional religionists may not recognize it. On Sundays Berry walks his Kentucky “home place,” the roughly 125 acres of bottom land in the region his family has farmed for more than 200 years. From the seventh-day silence, solitude, and natural world, Berry has crafted his Sabbath poems.

“Occasional poems” commemorate public events, but here Berry lays quiet markers to remember personal days in the life of one man. He writes in the preface: “though I am happy to think that poetry may be reclaiming its public life, I am equally happy to insist that poetry also has a private life that is more important to it and more necessary to us.”

The first half of “Son of God” features an upbeat and kindly Jesus spreading the good word in familiar, if occasionally over-simplified, biblical phraseology.

Then things get bloody — thought not quite as graphic as in 2004′s “The Passion of the Christ” — when Jesus is seized, beaten, and crucified. The production values are modest and the special effects uneven in this PG-13 repurposed and condensed version of the History Channel’s miniseries The Bible. (That series drew flack for casting an actor who resembled President Obama in the role of Satan. The film sidesteps any hint of controversy by keeping the devil out of this story.)

Son of God, which opens Friday, takes no real chances, opting for a moderately involving re-telling of an oft-told story.

Miles of yellow wheat bend; their leaves / rustle away and wait for the sun and wind.

—From “A Farewell, Age Ten”

We wondered what our walk should mean, / taking that un-march quietly; / the sun stared at our signs—"Thou shalt not kill.”

—From “Peace Walk”

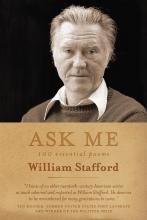

WILLIAM STAFFORD was a poet of the land and a conscience that fanned out over the land. Born in Hutchinson, Kan., 100 years ago—on Jan. 17, 1914—it was perhaps his early intimacy with space and sky that opened him to the mystery of human frailty.

At age 6, he saw two black students at his school being taunted by whites. He stood with them.

Another mystery: He who personifies the term national poet is largely unknown in his nation. Four new books (in his 79 years, Stafford published more than 50 books) published to coincide with his centennial might help redress this situation. Ask Me (Graywolf Press), from which the above excerpts are taken, brings to readers 100 “essential” Stafford poems dealing with his pacifism, his family, Native Americans, and the landscapes of his native Kansas and his adopted Oregon, where many centenary events are scheduled to take place.

AS AN EVANGELICAL pastor of a multiethnic church in New York City, I often find myself at the intersection of lively discussions about race. These conversations almost inevitably lead to a familiar question: What does the church do now? Maybe stated another way, “How do we work toward the dream of the beloved community?” This is why I find Edward Gilbreath’s Birmingham Revolution: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Epic Challenge to the Church to be a timely and necessary read.

While many books have been written on Dr. King and civil rights, Birmingham Revolution places King’s faith at the foreground of the writing. This is an important distinctive as King has often been co-opted, by conservative and liberal agendas alike. Yet history cannot deny that prayerful action, and a gospel that took seriously the social dimensions of human life, were at the very heart of King’s theology.

Birmingham Revolution hones in on the year 1963—a time when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference took the civil rights efforts into the bowels of structural racism. Brown vs. Board of Education had provided an important Supreme Court victory in 1954, but many forms of local resistance to desegregation prevailed in the South.

To compound the drama, many advocates in Alabama, both black and white, believed further progress should happen through legal means. They had a misplaced confidence that local structures would uphold federal law, despite the continued presence of the KKK and other such groups. Gilbreath explains Birmingham’s defining moment not only in confronting segregation, but also in challenging the subtler, unwittingly complicit voice of the moderate.

IN HER LATEST book, Sara Miles—author of the spiritual memoirs Take This Bread and Jesus Freak—goes where traditional and liturgical churches don’t regularly go: into the streets to push the boundaries of public worship. City of God chronicles a day in the life in San Francisco’s Mission District, on one Ash Wednesday when Miles and others from St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church offer “Ashes to Go,” a growing national movement within the Episcopal Church to perform the imposition of ashes outside the church walls on the first day of Lent.

Ash Wednesday works on the street because it has a broad ability to speak to people with “different beliefs about God and very different relationships to the church.” Even so, carrying the observance away from the altar has generated critics. Some liturgists have wondered if, without a proper church context, “the ashes become a meaningless affirmation of our earthly life,” or whether regular folks on the street can really appreciate the profundity of the human condition and mortality without the church to explain it to them. Trusting that people on the street will “get it,” Miles embarked on a day of crossing the traditional borders of worship space to smudge foreheads in McDonald’s, taquerias, hair salons, and botanicas.

Miles finds that traditional observance of liturgies such as Ash Wednesday helps reclaim the public language of sin and repentance in a progressive way. This kind of re-evaluation of sin in common life led her to realize how she’s also fallen short of the call to solidarity and deep communion with the city. “I aspired to be the kind of neighbor who knew everyone,” she writes, “I yearned to be in real relationship.” But her admittedly self-satisfied sense of fellowship didn’t match up to her interactions. She hadn’t even bothered to learn the last name of a young Latino activist on her block and confesses, “I prayed for my neighbors, but not so much with them, and it made me uncomfortable.”

SHORTLY AFTER his 1983 appointment as archbishop of San Salvador during the Salvadoran civil war, Arturo Rivera y Damas traveled to the United States. Rivera succeeded Archbishop Óscar Romero, who was martyred for his outspoken condemnation of the war. I asked a Maryknoll sister—who lost three community members, killed by the Salvadoran death squads—to assess Rivera’s comments to the U.S. media. “He does not have the gift of martyrdom,” she said.

That comment gives perspective to the efforts of nonviolent peace activists in the U.S., many of whom have risked their freedom, usually for short stints, as a consequence of civil disobedience. In Crossing the Line: Nonviolent Resisters Speak Out for Peace, Rosalie G. Riegle chronicles the action-to-court-to-jail-and-prison journeys of some of the last century’s most committed pacifists. While a few told harrowing stories, for the vast majority the consequences fell far short of martyrdom. This is not to belittle their efforts, but rather to beg the question: Why do so few Christians resist the violence and war-making of the U.S. government?

Riegle’s well-done compilation of 65 oral histories might prompt more people to step into the fray. To date, hundreds of U.S. pacifists have served hundreds of years, mostly in federal prison, for crossing lines, burning draft cards and draft files, and hammering on the weapons of war. At press time, three Catholic pacifists known as the Transform Now Plowshares—Sister Megan Rice, Greg Boertje-Obed (interviewed in Riegle’s book), and Michael Walli—await a January sentencing for federal felony charges stemming from cutting fences and hammering at the Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge, Tenn.

THE WOMEN IN Talking Taboo: American Christian Women Get Frank About Faith aren’t just frank. They are courageous, clever, and wildly passionate.

This anthology, edited by Erin S. Lane and Enuma C. Okoro, asks 40 women under 40 to respond to the question, “What taboos remain in the church at the intersection of faith and gender?” The result is a collection of stories by women of faith (Baptist, Presbyterian, Mennonite, Catholic, Unitarian Universalist, and more) in a variety of roles (pastor, mother, writer, teacher, student, and more).

The women share times they have felt shamed, alienated, discouraged, or alone as women seeking a home in the church. From addressing domestic violence to lust to pregnancy to the role of a woman pastor’s body, the stories are raw in the way first-person narrative calls upon honesty and vulnerability to trump perfect prose or style.

Anthologies often stick to one structural extreme: Either they are rigid and theme-driven, or loose and nomadic. Talking Taboo follows the latter. Lane’s introduction promises no arc of narrative, no solid take-away message. The stories are here, she writes, because women are agreeing to “speak for ourselves.”

I’VE RECENTLY spent time researching the vision of the U.S. through the lens of one film for every state, following the intuition that, as most movies are set in Southern California or New York (and there’s a lot more America where those didn’t come from), we need to examine Fight Club and On the Waterfront, Brokeback Mountain and Nashville no less than The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind to begin to capture the American dream life. It seems obvious, but it’s often dismissed: Contrasts between the states are mighty and rich. A Wyoming plain and a Sonoma vineyard, Hoboken and Harlem and Hot Springs, the Florida Keys and the Swannanoa Valley are all magnificent intersections of dreams and mistakes, which in honest art allows them to be places where the past can be faced.

And on that note, here’s my list of the 10 best U.S. films released in 2013:

The new Criterion Blu-ray John Cassavetes box set includes The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, the best entry to his work: A grimy thriller about one man trying to make art against the odds.

Jeff Bridges and Rosie Perez show us something more of how to be human in Fearless (newly available on Blu-ray), about a man who needs to die before he can live (and love).