Review

FOR ANYONE who’s sick of explaining that not all evangelicals are flag-waving, Quran-burning, gay-hating, science-skeptic, anti-abortion ralliers, The Evangelicals You Don’t Know: Introducing the Next Generation of Christians provides a boost of encouragement. Written by frequent USA Todaycontributor Tom Krattenmaker, this who’s who of “new-paradigm evangelicals” explains how a growing movement of Jesus-followers are “pulling American evangelicalism out of its late 20th-century rut and turning it into the jaw-dropping, life-changing, world-altering force they believe it ought to be.”

Unlike their predecessors, these new evangelicals are characterized by a willingness to collaborate with members of other religions and no religion for the common good, warm acceptance of LGBTQ folks, a rejection of the dualistic pro-life vs. pro-choice debate, and a desire to participate in mainstream culture rather than wage war against it. All this “while lessening their devotion to Jesus by not a single jot or tittle.”

Admittedly, the book’s cover photo doesn’t quite do justice to Krattenmaker’s observations. Featuring young worshipers in a dark sanctuary with hands uplifted and eyes closed, each apparently lost in a private moment of four-chord progression praise, the cover looks more like a Hillsong worship concert circa 1998 than cutting-edge 2013 evangelicals. (If you’re unfamiliar with the four-chord progression, Google “how to write a worship song in five minutes or less.” You’re welcome.)

THE EXPERIMENTAL psychologist Steven Pinker writes that what we think we have seen will shape what we expect to occur. It doesn’t make the news when people die peacefully in their sleep, or make love, or go for a walk in the countryside, but these things happen far more often—are much more the substance of life—than the acts of terror that preoccupy the media. It was horrifying when a British soldier was killed on an English street in May. But given the ensuing ethnic tension and communal judgment, it might have been useful, not merely accurate, to report that on the same day, almost 3 million British Muslims didn’t kill anyone. Because violence is a pre-emptive act (I kill you because you might kill me), when we keep telling the story that the threat of massive violence is ever-present, we will behave more violently.

According to Richard Rohr, the best criticism of the bad is the practice of the better. So perhaps attention to beauty is the best alternative to our cultural obsession with blood. For me, cinema can do this better than any other art form, and is uniquely capable of transporting the imagination. Recently I’ve traveled to the minds of retired Israeli security service leaders agonizing over their achievements and failures in The Gatekeepers, gone to Louisiana for a trip around the soul of a man trying to redeem himself in Mud, empathized with the tragic story of a man making bad choices to get into a better state in The Place Beyond the Pines, wondered at the creative process and bathed in the French countryside in Renoir, been reminded of and elevated into an imagining of love and its challenges in To the Wonder, and been provoked in Room 237 to consider whether or not Stanley Kubrick intended The Shining to be a lament for the genocide that built America.

Vampire Weekend are a little like a college-educated version of the rich young ruler in Mark 10. I say a little because, despite the fact that they have gotten flack for being “privileged, boat shoe and cardigan loving Ivy League graduates,” the New York-based foursome actually probably aren’t as wealthy as skeptics think, and the late 20-somethings probably haven’t been as straight edged as the rich young ruler. I mean, they’re rock stars. And even though they went to Columbia University, rock stars aren’t widely renowned for their moral rigidity.

But on Vampire Weekend’s third album, Modern Vampires of the City, which was released last month to critical acclaim and commercial success, we find lead singer Ezra Koenig asking honest questions of God, much like the young ruler.

On this album, the third in what Koenig sees as a trilogy, Vampire Weekend manage to mature their poppy, eclectic sound, drawing from all sorts of genres and international songs — as they normally do — but also exploring deep questions of morality, love, faith, and belief in complex ways.

INTRIGUING AND believable characters are part of what makes Janna McMahan’s new novel Anonymitya memorable read. Through the story, which is set in Austin, Texas, the author provides a well-constructed and evenly paced plot that brings to light critical themes around home and homelessness.

Early in the story we discover classic contrasts between the two protagonists. Lorelei is a young, homeless runaway whose daily grind revolves around finding food and a warm, safe place to sleep, while Emily’s major mission centers on branching out from her bartending job to take up a more artistic endeavor as a photographer. One buys organic greens from the high-end Whole Foods Market, while the other seeks sustenance in restaurant dumpsters.

This interesting juxtaposition of characters reels us in. But as we swim through the thickening plot, we discover the startling similarities between the two: Lorelei’s rebelliousness and grit compared to Emily’s disdain for the superficial lifestyle of big-box shopping and Corpus Christi vacations; Lorelei’s refusal to seek help and get off the streets weighed against Emily’s desire to break from the overindulgence she grew up around. As Emily’s mother, Barbara, observes, “Emily liked the frayed edges of life, a little dirt in the cracks.” It should come as no surprise that Emily takes an interest in Lorelei’s hardscrabble existence.

So much about Lorelei remains a mystery, which serves to add tension and compel the reader forward. We sense she is searching for something, and there’s no way to prepare for the powerful punch McMahan delivers when we discover what Lorelei’s quest is about.

TWO YEARS AGO, Jeff Chu found himself at a crossroads. Like many gay Christians, he felt disconnected—condemned by a wide swath of his fellow believers because of his sexual orientation, questioned because of his faith by some in the LGBTQ community who have been pushed out of the church by the words and actions of many Christians. To top it off, there was that lingering doubt, so common among those raised in evangelical households: Does Jesus really love me?

To answer that question, Chu—an award-winning writer for Time, The Wall Street Journal, andCondé Nast Portfolio and the grandson of a Southern Baptist preacher—took off on a yearlong cross-country pilgrimage, “asking the questions that have long frightened me.” What he encountered was a divided church, “led in large part by cowardly clergy who are called to be shepherds yet behave like sheep.”

Many of the pastors Chu contacted for the book refused to speak with him, citing their suspicion of him as a member of the so-called “‘liberal media elite’” or stating bluntly that engaging on such a controversial issue might jeopardize funding for a pet project. After speaking with Richard Land, then-president of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, and David Shelley, a Baptist minister from Tennessee affiliated with the Family Research Council, Chu concludes that they “devote much more time talking about legislation than about love.”

Then there are those he interviewed who are known more for screaming than talking. In meeting with members of the infamous Westboro Baptist Church, Chu does not shy away from controversy—or his own fears. “Some nights before my departure,” he recalls of the days before his trip to Kansas, “I had nightmares, and many mornings I’d wake with my jaw tight and teeth clenched.” His encounter with Rev. Fred Phelps, the grizzled, homophobic pastor of the church, is perhaps the most riveting of the book, culminating in a surreal, grudging offer of friendship from Phelps.

ETHICS ASKS the questions: What is right to do? How do we know? David P. Gushee puts the concept of the sacredness of human life at the center of his moral reasoning. A professor of Christian ethics at Mercer University in Atlanta, Gushee has given us a work that is an important milestone on the road of constructive Christian ethics.

In this book Gushee has set himself a large and ambitious goal. He writes, “I am proposing that, rightly understood, a moral norm called the sacredness of life should be central to the moral vision and practice of followers of Christ.”

He seeks to ground this moral norm in scriptural authority and in the Christian tradition at its best. His survey of scripture and of Christian history is truly impressive, considering most of the major elements of the Christian theological and ethical traditions, including the current thinking of liberation theology. He demonstrates knowledge of the feminist critique of scripture, and he at least mentions eco-feminism. The bibliography alone is worth the price of the book.

Moreover, Gushee also considers such important Enlightenment thinkers as John Locke and Immanuel Kant. He devotes a chapter each to German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and to the Nazi desecration of human life. There is much food for thought here.

For me, however, the book is primarily descriptive. And it does not provide an explanatory framework to help us understand why scripture and the Christian tradition have led the way in both the recognition of the sacredness of human life and in the violation of this holiness. It would have been helpful for Gushee to give us a brief discussion of Ernst Troeltsch, who in his two-volume The Social Teachings of the Christian Churches enables us to see that the line of demarcation between the church and the world is porous to the point that there is always interpenetration between the two. Church teachings leaven and flavor the moral thinking of the world outside its doors while the world’s often destructive ideologies come to church every Sunday and sit down on the front pew and sometimes preach from the pulpit.

HOW IS IT that a miniseries based on the Good Book could evoke sectarian and violent notions of the Divine that would have seemed backward to some even back in the era of melodramatic biblical epic cinema? The History channel’s The Bible, like so much of so-called “religious pop culture,” seemed to be the product of good people trying to do a good thing, but at best putting the desire to convey a particular message ahead of making the best artwork for the medium.

The politics of The Bible seemed to perpetuate an “us vs. them” lens. It left me wishing for a treatment of scripture presented from the perspective of the marginalized, instead of a portrayal of “victory” as being the deaths of people considered different. Couldn’t someone make an Exodus movie about Moses’ neighbors—you know, the ones who saw God’s favor rest on the boy next door, while their son was killed by a psychopathic king? Or one focused on the myriad people groups considered “unclean” and worthy of genocide at the hands of those who claim to speak for God? Or a rendering of John’s Revelation that understands it as a poem about remarkable beginnings, the battles of the human heart, and a love willing to remake the world to set us free from the traps we’ve laid for ourselves? You don’t even have to be that controversial—can’t someone just make a decent movie about Ruth or any of the many cool women in the gospels?

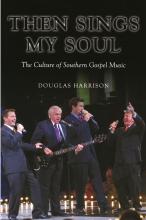

IF YOU GREW up like I did—surrounded by PraiseGathering devotees and with Gaither Family VHS tapes stacked on the home entertainment system shelves—you probably have a frame of reference for Douglas Harrison’s Then Sings My Soul. If you weren’t raised on such a specific Bible Belt diet of white male quartets and singspirations, Harrison’s use of the term “Southern gospel” may initially seem confusing, if not meaningless.

According to Harrison, Southern gospel wasn’t labeled as such until the 1970s, and the label didn’t catch on with mainstream audiences until the 1980s. Before then, all genres of gospel—sacred music spanning regions, decades, ethnic heritages, and faith-based traditions—were given the broad label. As Harrison defines it in what is arguably one of the first contemporary attempts to do so, Southern gospel is a participatory style descending from a “post-Civil War recreation culture built around singing schools and community (or ‘convention’) singings popular among poor and working-class whites throughout the South and Midwest.” While he notes that most rigorous investigations of gospel’s longevity and legacy refer to black gospel, Harrison departs from this framework and instead focuses on the likes of the Blackwood Brothers Quartet, The Cathedrals, and gospel impresario Bill Gaither, pasty proselytizers without whom the 20th century gospel movement would not exist.

Harrison has been blogging (at averyfineline.com) about Southern gospel for the past decade, during which he’s showcased his deep knowledge and fondness for the genre’s mid-tempo nostalgic modernism, a retro style performed without irony by up-and-coming artists. His is an outsider’s, nonbeliever’s ode to professional, commercialized gospel entertainment, a style attributed to a variety of performers. “Southern gospel was what Elvis Presley really wanted to sing,” Harrison notes. He goes on to identify Southern gospel’s evangelists as a cluster of record and distribution labels, organizations such as the National Quartet Convention, and the Gaither Homecoming phenomenon (including videos, music recordings, concert tours, and even cruises under that branding), all of which share a common historical, economic, social, and cultural heritage.

LAUGHTER IS Sacred Space: The Not-So-Typical Journey of a Mennonite Actor has the narrative arc of a classic Greek tragedy: Boy from religious sect grows up, becomes a butcher, goes to seminary, then finds acting acclaim as part of a duo (Ted & Lee), only to have his comedic partner die by suicide, after which the show must go on and does.

Ted Swartz’s story is a bittersweet tale, with emphasis on the sweet. It is told in the structure of a five-act play. What originally drew me was the fact that Swartz’s late acting partner, Lee Eshleman, was a classmate of mine at Eastern Mennonite University, where we were art majors to-gether. Eshleman was easily the most talented among us. (His line drawings illustrate the book.) He was also smart, funny, and regal.

After I left EMU, unmarried and pregnant, I would sometimes see Eshleman’s name on the masthead of the alumni magazine and think, “I wish I had it as together as Lee does.” It was a shock to hear that, like my own son, Eshleman too had died by suicide.

His death and its impact on Swartz take up a good deal of space in this memoir. The duo worked together for 20 years, and Swartz is honest about the ups and downs of their friendship. He does a great job of communicating that Eshleman was much more than his suicide or his bipolar disorder. He was that extraordinary person I remember.

THERE IS STILL a political definition of “Christian” out there that is depressingly familiar: the right-wing voting, Fox News-sourced agitprop spewer who uses Jesus to shoehorn others into something the actual Lord of the universe could care less about. Lillian Daniel is not going to take this definition anymore, but she’s not mad as hell. She’s winsome as heaven. Her humor clears the way for her preaching to hit home, and her love for the church, both her congregation and universal, anchors this work. Give it out to your friends and to strangers on the street.

First, Daniel’s humor: It is hard to give examples of her humor without them falling flat. She’s at her droll best when the reader’s defenses aren’t up. This isn’t the humor of the warm-up act before the preacher gets on to something serious—she often drives her meatiest points home with her funniest stuff. For example, a running motif in the book is the airplane companion who thinks he’s being edgy when he says to the pastor beside him that he sees God in rainbows and sunsets. This “spiritual but not religious” mindset is now the bland norm in America, not some spectacular new revelation: “They are far too busy being original to discover that they are not.”

Some of Daniel’s most withering observations are reserved for the mainline church she loves: the sneering religious critic is told “all those questions actually make him a very good mainline Protestant.” The self-congratulatory short-term missionary who comes home convinced how “lucky” she is to live in America receives this barb: “When generosity begets stupidity it wasn’t really generosity to begin with.”

- Preaching God's Transforming Justice, edited by Dale P. Andrews, Dawn Ottoni-Wilhelm, and Ronald J. Allen, is a lectionary commentary series from Westminster John Knox Press that helps preachers better proclaim the biblical call to be agents of God's love and justice in the world. Embodying that mission in a small but key way, the 90 contributors include close to equal numbers of women and men and represent significant ethnic and racial diversity. Each volume provides commentary for all the year's lectionary days, plus essays on 22 "Holy Days of Justice," from World AIDS Day to Children's Sabbaths. The first two volumes, for Years B and C, are already available. The Year A volume is due for release in August.

- The Revised Common Lectionary's readings for each Sunday—four selected scriptures, generally one each from the Psalms, the rest of the Hebrew Bible, the epistles, and the gospels—are heard by millions of Christians each week. Timothy Matthew Slemmons, an assistant professor of homiletics and worship at the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary, has been captivated by what isn't heard. In Year D: A Quadrennial Supplement to the Revised Common Lectionary (Cascade Books), he argues for an expansion of the lectionary in order to present a fuller portrait of God's revelation. It includes a proposed one-year set of readings that does not shy away from many difficult texts, including from the Psalms and prophets.

DREAMS CAN serve a powerful purpose. Jacob dreamed a ladder and was renamed Israel. Joseph dreamed the sun and moon and stars and was sold into slavery. The magi dreamed a warning and returned home by way of another road.

Years ago I had a dream. I sat, a child, on a dirt floor. Around me paced a horse, saddled, ready. In front stood an immense door, cathedral-tall and brooding. And though open, the space within was dark. I was holding a light. And in the dream, I knew we were to bring light into that darkness. And the darkness—the darkness was the church.

In Truth Speaks to Power: The Countercultural Nature of Scripture, Walter Brueggemann, professor emeritus of Old Testament at Columbia Theological Seminary, bears light to the exegetical (seminary lingo for interpretive) work and examination of the interplay between truth and power found in both familiar and less familiar narratives of Old Testament scripture. Rigorous in content, the read is nevertheless accessible to scholar and novice alike.

Brueggemann's concern with the interplay of truth and power rests on the observation that far too often truth, even biblical truth, is found colluding with and legitimizing the self-serving and self-preserving agenda of totalistic and monopolizing authorities. To use biblical imagery, truth sides with the Pharaohs and the Solomons of the world and not with those on its margins and periphery.

The first two chapters draw on Brueggemann's impressive scholarship of Old Testament text and narrative to paint a disconcerting picture where not only are the bad guys truly bad, the good guys aren't any better. Take Joseph, the Technicolor-dreamer-slave become all-powerful-vizier (think prime minister) of Egypt. It is Joseph's land acquisition scheme, strategically implemented amid drought and famine, that results in Pharaoh controlling most of Egypt's wealth. It is Joseph who creates a permanent peasant underclass—the very class that will cry out for liberation from the injustice of having to bake bricks with no straw. And Solomon—well, you know something's gone terribly amiss when your empire accumulates "six hundred sixty-six talents of gold" (1 Kings 10:14) each year. If you don't see the editorial subtext, write it out numerically. Ouch!

Glorybound, by Jessie van Eerden. WordFarm.

A luminous debut novel that features two sisters shaped by family estrangement and holiness faith in a hard-scrabble West Virginia mining town.

Hold It 'Til It Hurts, by T. Geronimo Johnson. Coffee House Press.

This debut novel and 2013 PEN/Faulkner-award nominee follows an African-American combat vet in his search for his missing sibling, a journey tangled with the fallout of war and race.

The Mirrored World, by Debra Dean. Harper.

A reimagining of the life of an 18th century Russian saint, Xenia of St. Petersburg, set against the excesses of the royal court.

Benediction, by Kent Haruf. Knopf.

An elderly man in a small Colorado town receives a terminal diagnosis, and the intricacies of human community are revealed in the stories of the people who gather around him.

WHEN A COLLEAGUE told me Sojourners had received a review copy of the latest Thursday Next novel by Jasper Fforde, I was delighted—and confused. My delight came because I’m a huge fan of the series, whose protagonist Thursday lives in an alternate-reality U.K. and, in previous novels, has worked for Jurisfiction, the policing agency within fiction. My favorite scene was when, several novels back, she helped Great Expectations’ Miss Havisham moderate an anger management group in Wuthering Heights, set up to keep it from going the way of “that once gentle comedy of manners, ‘Titus Andronicus.’”

However, it was unclear why anyone would send a book from this series to a Christian social justice-oriented magazine. My best guess, as I gleefully devoured The Woman Who Died A Lot, was that some hilariously over-optimistic publicist thought we’d be interested in the novel’s subplot in which God reveals Godself by smiting various cities with columns of fire—sometimes in response to sin, sometimes to “unimaginative architecture, poor restaurants, or even an overly aggressive parking fine regime.” Thursday’s hometown of Swindon is next on the smite list, possibly to increase God’s bargaining position against the locally based Global Standard Deity church. The GSD, having unified the world’s religions, plans to use its “collective bargaining powers” to open formal negotiations with God, starting with the question, “What, precisely, is the point of all this?”

If I were Brian McLaren, I could no doubt get mileage out of this negotiating-with-God idea, and out of the novel’s various speculations about whether notbelieving might make God (or, in a separate subplot, an asteroid hurtling toward the Earth) cease to exist. Other storylines—a villain who can alter memories convinces Thursday she has an extra child; Thursday’s teenage son Friday is apparently fated to murder someone who may or may not be an irredeemable louse—could, at a stretch, fuel theological debate about identity or free will.

SOME BOOKS MAKE you want to sit down with the author on a sunny afternoon for a nice cup of tea. You would be excited to talk about how the book resonated with your own journey. For me, From Willow Creek to Sacred Heart: Rekindling My Love for Catholicism, by Chris Haw, is such a book.

Haw, a young, passionate, and deeply self-reflective theologian, shares his spiritual memoir. Part one recounts Haw's faith journey from a childhood as a lukewarm Catholic to teenage years at the evangelical megachurch Willow Creek, to college—including brief but powerful months in Belize, as well as days of protest against the Iraq war—and eventually to his present life in the apocalyptic landscape of Camden, N.J., where he returned to the Catholic Church.

Part two presents Haw's theological reflections on a variety of questions he has raised along his journey. He also focuses on common objections against the Catholic Church, such as the nature of the Mass as a sacrifice, the church's reliance on human tradition over the Bible, its hierarchical system, alleged ritualism, embellished architecture and ornaments, devastating scandals—including child molestation—and so on. Haw explores such challenging issues thoughtfully and courageously, while humbly accepting that he still struggles with them. Despite it all, Haw longs to see beauty and hope furthered through the Catholic Church.

I am a Catholic convert. I was raised in a Methodist family and trained in Protestant seminaries. By the time I decided to convert to Catholicism, I was starting my first year in the doctoral program of theological studies at Emory University. Feminist theology played a central role in both my theological education and spiritual formation, and it continues to today.

IN EARLY AUGUST 2010, 10 aid workers were murdered, execution-style, in the province of Badakhshan, in northeastern Afghanistan. Among them were six Americans, two Afghans, a Briton, and a German, all part of a medical mission. It was the deadliest attack on aid workers the country had seen.

Dan Terry, 63, an American humanitarian who, with his family, had called Afghanistan home for more than 30 years, was among the dead.

What compels a person to risk his or her life in a foreign land so riddled with conflict? For Terry it was simple—he was called to a life of peacemaking and service.

A friend of Terry's since childhood, writer Jonathan Larson draws us into Terry's passionate character and the vision he shared with friends in Afghanistan: reconciliation and dialogue. "In the end, we're all knotted into the same carpet," Terry was fond of saying. From a swath of interviews with family, friends, and colleagues, both Western and Afghan, Larson has assembled "oral narratives," sharing with us the exhilarating life of a generous and gentle man, heroic but humble.

The best advice I received as a humanitarian aid worker in Afghanistan was from a leader cut from the same cloth as Terry: "Make no assumptions" and "listen first." We too often accept media caricatures of the other, labels that shut down discourse and clamp off possibility and hope. Challenging this, Terry insisted on the unwavering potential of each person he met. "Categorical 'enemies' have rescued me ... again and again," he once wrote to friends.

DANIEL BELL'SThe Economy of Desire juxtaposes Christianity and capitalism, situating both in the context of postmodernity. The main argument of the book is that performing works of mercy—both corporal and spiritual—constitutes an alternative economy that can resist capitalism. Capitalism, in Bell's construal, is an economic system founded on voluntary contracts, private property, and an ideological regime where the rule of the market transcends the rule of law and disregards the reign of God in Christ.

The author draws on the work of philosophers Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze to set up a philosophical framework for talking about power and desire. His treatment of Foucaultian insights on the ubiquity of power is meant to decenter the state as the primary engine of social change. Deleuze's work builds on Foucault's argument by conceptualizing people—and society at large—as flows of desire. Taken together, the claim is potentially but not necessarily democratic: Social structures organize desire in particular ways and are malleable due to the fact that power resides not only in the state or market but in the relational networks of everyday people. Under this account, for instance, the typical presidential election is not simply about securing votes, but about directing the aspirations and actions of the electorate toward a collective passion for growing the economy, expanding the middle class, and so on. Capitalism, for Bell, secures our loyalty because it shapes what we do as well as what we desire.

A few strengths of the book stand out. It contains a lucid discussion of the difference between commutative (fair contracts) and distributive (fair proportion of wealth, power, and other goods) justice within society. The scope of the author's analysis is also impressive. Bell substantively engages the arguments of diverse figures from Adam Smith, Milton Friedman, and Friedrich von Hayek to Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, and Martin Luther. Moreover, Bell's contention that proponents of capitalism effectively deny the possibility of social holiness is worth the price of the book.

DR. JAMES BROWNSON'S book Bible, Gender, Sexuality: Reframing the Church's Debate on Same-Sex Relationships calls us all into a deeper engagement with the Bible itself, exploring in the most thoughtful and thorough ways not just what it says but, more important, what these inspired words of revelation truly mean.

On the one hand, Brownson argues that many of those upholding a traditional Christian view of same-sex relationships have made unwarranted generalizations and interpretations of biblical texts that require far more careful and contextual scrutiny. On the other hand, those advocating a revised understanding often emphasize so strongly the contextual and historical limitations of various texts that biblical wisdom seems confined only to the broadest affirmations of love and justice.

For all, Brownson invites us into a far more authentic, creative, and probing encounter with the Bible as we consider the ethical questions and pastoral challenges presented by contemporary same-sex relationships in society and in our congregations. In so doing, Brownson does not begin by focusing on the oft-cited seven biblical passages seen as relating to homosexuality. Rather, he starts by examining the underlying biblical assumptions made by those holding to a traditional view, and dissecting the undergirding perspectives held by those advocating a revised view.

A FEW YEARS before American naturalist John Muir heeded the call of the California mountains, the boggy swamps and towering palm trees of a much flatter territory beckoned him south to the Gulf Coast states. As for many young travelers before and since, a journey into exotic lands was a path toward vocational and spiritual enlightenment for Muir.

In Restless Fires: Young John Muir's Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf in 1867-68, Whitworth University emeritus professor James B. Hunt explores how that trip forever changed Muir's perspectives on humans' relationship to the natural environment. Digging deep into Muir's childhood, Hunt details how Muir's theological transformation shaped his environmental stewardship.

It's a wonder Muir maintained any divine belief system. Muir's Scottish father, a strict practitioner of Campbellite Christianity, nearly beat faith out of him, combining forced Bible memorization with harsh physical punishment. Hunt contends an unfortunate twist of fate may have opened the door to Muir's escape from suffocating under zealous religion and monotonous factory life. He lost an eye while working as a machinist, which caused temporary sympathetic blindness in his other eye. As soon as Muir was able to see again, he left the Midwest in a southward walk toward what he imagined was North America's Eden.

OVER DINNER my friends and I reflected recently on the headlines that surprised us last year. A few were especially painful: former Rep. Todd Akin's comment that "legitimate" rapes do not lead to pregnancies; failed Senate candidate Richard Mourdock's comment that a pregnancy from rape is "something that God intended to happen"; and the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), in effect since 1994, ending as the 112th Congress closed without reauthorizing it. All reminded me why the second edition of The Cry of Tamar: Violence Against Women and the Church's Response, by Pamela Cooper-White, is still needed almost 20 years since its first edition.

The Cry of Tamar reads as a graduate textbook on providing pastoral support for the victims of violence against women. It weaves pastoral counseling methods and social and psychological theories in dialogue with biblical exegesis and constructive theology to give clergy, pastoral caregivers, and religious leaders tools to help victims of violence and the larger Christ-community.

The story of Tamar, a girl raped 3,000 years ago in Jerusalem, frames and guides the book's goal of providing healing to the girls and women who are victims of violence today.

Advocacy, prevention, and intervention to stop violence against women have advanced since the 1995 first edition. Religious communities and congregations have become more informed about how to care and respond to both victims and perpetrators. But the need for increased awareness and education is ongoing. This second edition is an effort to update the conversation and keep it on the table.