Palestine

For many of us who were raised Christian, our earliest memories of Christmas may have featured the town of Bethlehem. Whether through songs or the stories in scripture, this quaint town that welcomed the Christ child took on a central role in our faith.

Our shared planet is crumbling under the weight of human greed and exploitation; our neighbors are being snatched up and disappeared from our communities; and money for jobs and education is being used to fund wars and genocide. And I’m expected to believe that God is good?

THE SEASON OF Advent is over, but the season of our waiting is not. There is still so much we long to see brought to fruition. Every morning’s news confirms the ache. We are pining for so much to be made right in a world that has gone so wrong. Christmas may have marked the end of Advent, but the liturgical year has only just begun. In other words, Christ has been born, but there is still a lot of story to be played out. What a great reminder as we head into yet another year that looks bleak at the outset: This story we are living in isn’t done yet. There is more to come, and some of it is very good news.

Just as it will take time for the Christ child to grow into the savior the world needs him to be, in every era of human history, the growth of justice takes time. Recognizing the slow pace at which the kin-dom of God unfolds does not mean we lie down on our backs and abdicate responsibility, but it does mean we have hope as we both labor and rest. No matter how dismal it may look out there, justice is on its way.

January’s readings take us into conversation with texts aching for justice and longing for homecoming, helping us sense when to listen and when to speak, when to hold still and when to move. We are encouraged to be tender with each other as we wait, to hold on tight to hope, and when the moment calls, to act with conviction.

The empire asked for us to register our identity.

145 kilometers,

15 checkpoints.

Every blockade,

Joseph was stopped and frisked,

and I was undressed.

FOR THE THIRD year in a row, Advent in Palestine is not a season of joy. Even with the tenuous ceasefire, Advent is lived in the shadow of genocide, walls, checkpoints, ethnic cleansing, dispossession, and fear.

For many Palestinians, these days of waiting and preparation are overshadowed by mourning for loved ones lost, for homes demolished, for lands taken. In Bethlehem itself, where the Christian story began, streets that should be filled with song and light are burdened with grief and lament. The hymns of waiting mingle with the cries of the bereaved, displaced, imprisoned, and the starving.

In the land where the gospel of Jesus first unfolded, the nearness of Advent is most real. The Christmas story doesn’t look like comfort, plenty, and “toys in every store.” The original narrative bears a much closer resemblance to the times in which we, Palestinians, currently live.

With a fragile ceasefire between Israel and Hamas in place, it is tempting for many in the West to ignore the broader issues that Palestinians still face: Namely, increased settler violence and the state of Israel annexing more Palestinian land. I went to Palestine in August, while the war that was not a war still raged, and I saw firsthand the dire reality of Palestinians in the West Bank.

Joyous Palestinians rushed to embrace prisoners freed under a U.S.-brokered ceasefire agreement as they arrived by bus to the occupied West Bank and Gaza on Monday.

The prisoners were released after the Hamas militant group freed the last 20 living hostages taken during the Oct. 7, 2023, attacks that precipitated the war in Gaza.

Under the deal, Israel is set to release 250 Palestinians convicted of murder and other serious crimes as well as 1,700 Palestinians detained in Gaza since the war began, 22 Palestinian minors, and the bodies of 360 militants.

Several thousand people gathered inside and around the Nasser Hospital in Khan Younis in the southern Gaza Strip, awaiting the arrival of freed prisoners, with some waving Palestinian flags and others holding pictures of their relatives.

Fighting back tears, one woman who asked to be identified as Um Ahmed said she said that despite her joy at the release, she still had “mixed feelings” about the day.

In August, at least 20 people were killed in an Israeli attack on Nasser Hospital in southern Gaza. According to MSNBC, Israel struck the hospital at least four times, killing journalists, health workers, and emergency response personnel, many of whom were responding to the initial round of bombings.

Last weekend, I visited my home state of Illinois to attend the Church at the Crossroads conference, which was held at Parkview Community Church in Glen Ellyn. Conference organizers estimated that 580 attended in person and 300 more joined virtually. The conference was convened to encourage American evangelicals to listen to Palestinian Christians and to confront and correct those who use scripture to “justify war, occupation, or silence” in the face of the escalating violence in Israel and Palestine.

Practically speaking, though, what was the point of this shindig?

The Fantastic Four: First Steps starts out with a trade proposal of the highest stakes. Galactus, the world-eating villain of Marvel’s latest reboot, will spare the Earth from his insatiable hunger in exchange for one child.

The child on the cosmic bargaining table is Franklin, son of Reed Richards, aka “Mister Fantastic” (a subdued Pedro Pascal) and Sue Storm, aka “The Invisible Woman” (Vanessa Kirby, who really gets to shine as the Fantastic Four’s leader).

Most would agree with the Nigerian-British singer-songwriter Sade that we don’t need any more war, but we are in desperate need of just a little peace. So, what do we do when it becomes clear that the people advocating for that peace are being thrown in prison or portrayed as “terrorists” who are interfering with the “peace process” in the Middle East due to their advocacy for Palestinian human rights?

Mohsen Mahdawi, who is a legal permanent resident in the U.S., was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents on April 14 as he exited his citizenship interview at a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services office in Vermont. President Donald Trump’s administration accused Mahdawi of potentially undermining the peace process in the Middle East. But despite this accusation, the government has not charged Mahdawi with a crime. Mahdawi was released from detention on April 30 after U.S. District Judge Geoffrey Crawford granted him bail, commenting that Mahdawi had “made substantial claims that his detention was in retaliation for his protected speech.”

In 2002, director Danny Boyle and screenwriter Alex Garland released a post-apocalyptic horror movie that would redefine the zombie genre forever. 28 Days Later was not only ambitious for its experimental cinematography and reliance on relatively obscure actors, but also because of its critical commentary on violence and militarism. Boyle and Garland have partnered up again for the newest installment in the 28 Days Later film series, with the release 28 Years Later (now playing in theaters).

There’s nothing wrong with a gross and scary zombie movie that just stops there, but the 28 Days Later film series offers more than jump scares and blood-barfing, fast-moving zombies, which are called “infected” in the films.

I went on a trip to the American South with the Telos Group, a nonprofit dedicated to equipping people to advocate for peace and reconciliation amid conflict. The purpose of the delegation was to help Palestinians learn about the histories and current realities of the Black and Indigenous struggle for justice in the United States.

Francis called the church hours after the war in Gaza began in October 2023, Antone said, the start of what the Vatican News Service would describe as a nightly routine throughout the war. He would make sure to speak not only to the priest but to everyone else in the room, Antone said.

At some point this Easter Weekend, Christians will be reflecting on the final words that Jesus spoke from the cross, sometimes referred to as the seven last words of Jesus.

When I was younger, I was convinced that System of a Down’s “Chop Suey!” was a Christian song because lead vocalist and lyricist Serj Tankian incorporated Jesus’ final declarations into the song. But dissimilar to the order that Christians have typically arranged Jesus’ final words, the song first quotes the cry of reunion and then climaxes with the cry of dereliction.

Considering that the Roman Empire believed Jesus was a terrorist and crucified him as one, emphasizing the cry of dereliction seems apt.

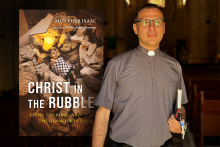

In ‘Christ in the Rubble,’ Palestinian pastor Rev. Munther Isaac surveys the devastation of his homeland and finds God in the most unexpected places.

Since arriving to the White House, the richest man in the world, Elon Musk, has been on a destructive whirlwind through the federal government. At the behest of President Trump, the South African billionaire and chief of the Department of Government Efficiency has led an effort to illegally gut numerous federal agencies, fire tens of thousands of federal workers, and perpetrate fraud while claiming to root it out.

Regarding the seemingly intentional turmoil of Musk’s actions, Trump bragged at the Conservative Political Action Conference that his administration had “effectively ended the left-wing scam known as USAID. The agency’s name has been removed from its former building, and that space will now house agents from Customs and Border Patrol.” Taken alone, these actions have the makings of an oligarchic heist or a coup that cripples the government’s capacity to provide and protect public goods.

But within a wider aperture of the administration’s priorities — ripping apart families, hoping to establish concentration camps, offering refugee status to white Afrikaners, attacking trans people, and engaging in a “war on woke” across institutions — a coherence comes into focus amid the chaos. These are men who destroy to build a racial hierarchy in service of their own wealth and profit. Or as political commentator Elie Mystal of The Nation has framed it, they are bringing a “a neo-apartheid economic agenda to the US government.”

Amid the fragile ceasefire, the exchange of hostages, and the temporary pause in Israel’s genocidal onslaught against Gazans, nearly six hundred Christians huddle together in one of Gaza’s battered churches, their prayers rising above the rubble as a defiant testament to their faith and resilience. Among them, Gazan Christian George Antone boldly declares, “For us, as Christians, we are not leaving Gaza. We will remain in Gaza and help people in Gaza reconstruct their houses, rebuild the streets. Yes, we will stay in Gaza. We are not leaving.”

Antone’s words stand in stark contrast to the explosive press conference at the White House on Feb. 4, when President Donald Trump brazenly suggested that the United States should “effectively own” Gaza, proposing to turn it into a real estate venture while displacing Palestinians from their homeland and relocating them to neighboring countries.

Israel and Hamas agreed to a deal to halt fighting in Gaza and exchange Israeli hostages for Palestinian prisoners, an official briefed on the deal told Reuters on Wednesday, opening the way to a possible end to a 15-month war that has upended the Middle East.

When I visited Rev. Munther Isaac in Bethlehem, the West Bank, in October, he mentioned that he was previously opposed to liberation theologian James H. Cone. Isaac was trained in theologically conservative teachings, growing up in a conservative church and then leaving Palestine to attend a conservative seminary in the U.S.