Palestine

When my wife, Karen, and I lived in Jerusalem, we awakened each morning to see the rising sun shining on the Mount of Pentecost. It is the traditional site of the coming of the Holy Spirit (Acts 2), the Upper Room, and King David’s tomb.

The power of that image remains in our consciousness. But even more compelling was the view from our hillside terrace where we had breakfast and entertained our friends. Below, between our home and the holy “mountain” 100 yards across the Hinnom Valley, was the still garbage-strewn site of the Moloch cult’s altar where babies were sacrificed to the presumed angry Israeli god — a place condemned as cursed, with no buildings for 2,500 years.

The contrast was always startling. Land, hills, trees, military power, and false religion have become the idolatrous substitute for God himself, as church historian Martin Marty has noted. And the fact is that “children” such as Rachel Corrie, Israeli soldiers, Palestinian stone throwers, and totally innocent little infants are dying daily, as contemporary sacrifices to an idolatrous god.

The Supreme Court on June 8 declined to insert itself into the middle of the Israeli-Palestinian issue by second-guessing U.S. policy on Jerusalem.

Ruling just a few months after a feud between President Obama and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the justices refused to allow Americans born in Jerusalem to have their passports changed to reflect Israel as their birthplace, as Congress demanded more than a decade ago.

In denying the challenge waged by the Jewish parents of a 12-year-old almost since his birth in 2002, a majority of justices heeded the State Department’s warning that a simple passport alteration could “provoke uproar throughout the Arab and Muslim world.”

The Vatican’s decision to recognize Palestine as a sovereign state on May 13 angered Israeli officials.

The move comes four days before the first-ever canonization of two Palestinian nuns and it solidifies the standing of Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, who is scheduled to meet with Pope Francis at the Vatican on Saturday.

Israeli Foreign Ministry spokesman Emmanuel Nahshon told The Times of Israel that the government is “disappointed by the decision. We believe that such a decision is not conducive to bringing the Palestinians back to the negotiating table.”

The Vatican announced it will recognize the state of Palestine in a treaty concluded May 13.

The treaty is awaiting formal approval and signing, but it is already being recognized as a major statement of support for a Palestian state in the historically contested region.

The pope has long signaled his support of a state. The language of the treaty, while not yet signed, has alarmed Israelis but invigorated the Palestinian case for statehood, The New York Times reports.

For the past year, the Vatican had informally referred to the country as “state of Palestine,” in its yearbook as well as in its program for Francis’ 2014 visit to the Holy Land.

Formal recognition of a Palestinian state by the Vatican, which has deep religious interests in the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories that include Christian holy sites, lends a powerful signal of legitimacy to the efforts by the Palestinian Authority’s president, Mahmoud Abbas, to achieve statehood despite the long paralyzed Israeli-Palestinian peace process.

Read more from The New York Times here.

Pope Francis will bestow sainthood on two Palestinian nuns on May 17, a move that’s being seen as giving hope to the conflict-wracked Middle East and shining the spotlight on the plight of Christians in the region.

Sisters Maria Baouardy and Mary Alphonsine Danil Ghattas are due to be canonized by the pontiff along with two other 19th-century nuns, Sister Jeanne Emilie de Villeneuve, from France, and Italian Sister Maria Cristina dell’Immacolata.

The coming canonizations have been described by the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, Fouad Twal, as a “sign of hope” for the region.

Let me tell you about a married couple. They have been together for many years. Their marriage has had some good moments, but there have also been periods of verbal and physical abuse. Finally, the wife tells her husband that she is considering leaving the marriage. She knows she has options. She can go to a shelter for battered wives, and even find her own place to live in safety and security.

As she starts her car in the garage, her husband runs after her. He drops to his knees and begs: “Please don’t go. I won’t be ‘me’ without you!”

Does she put her foot on the brake, shut off the engine and go back into the house? Does she stay in what has become a very troubled marriage?

That is precisely the question that many Jews in Europe have been asking themselves. More than 7,000 French Jews have moved to Israel in the last year, and there are clear signs others will follow.

This is huge. France has the third-largest Jewish community in the world.

IN 1973, IMMEDIATELY following the Yom Kippur War, I watched the movie Exodus. I was so swept up by Leon Uris’ depiction of the Zionist struggle that I wrote in my journal, “The U.S. should do everything it can to defend the state of Israel!”

Two years later, I read a history of the Arab-Israeli conflict in a serialized encyclopedia of World War II. It transformed me into an impassioned defender of Palestinian rights. Clearly, the historical narrative one accepts is critical to determining how a conflict is understood.

Jo Roberts’ book Contested Land, Contested Memory: Israel’s Jews and Arabs and the Ghosts of Catastrophe challenges the nationalist mythologies of both Israelis and Palestinians, peoples largely in denial of each other’s histories. With exhaustive research and numerous personal interviews, Roberts has created a book that is both sensitive to and challenging for partisans of either side.

Roberts begins with the story of an Israeli Jew whose memories of idyllic childhood vacations in a particular village are shattered when she learns from a Palestinian boyfriend that his family was displaced from that village by Israeli soldiers in 1948. Roberts goes on to offer a history of Zionism that is not without its share of heartbreak. From persecution in Catholic Spain to the Dreyfus affair in France and government-sanctioned pogroms in Russia, she reminds us of the prevalence and ferocity of anti-Semitism, which led many to join the movement to create a Jewish state in Palestine. She includes a report to President Truman about 250,000 Holocaust survivors, who in late 1945 were still confined in former slave labor and concentration camps because no country, including the U.S., would accept them as refugees. Roberts makes a convincing case that many Jews went to Palestine because they literally “had nowhere else to go.”

Boys on a beach,

women with cookpots,

men bombing tender patches of mint.

There is no righteous position.

Only a place where brown feet

touch the earth.

Maybe you call it yours.

Maybe someone else runs it.

What do you prefer?

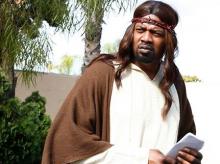

JESUS RETURNED this past August. Or at least a new depiction of him appeared on late-night cable television, in the comedy Black Jesus, created by Aaron McGruder (of The Boondocks). There was no rapture, and no subsequent tribulation, beyond what passes for normal these days. Instead Jesus appeared, as he did in Palestine, in a manner both obscure and mysterious. And, again, his incarnation became a scandal among some of the powerful and pious.

In Black Jesus, on the Adult Swim network, the second person of the Trinity turns up one day on the streets of Compton, a very poor and heavily African-American community in southern Los Angeles County. Played by a tall and beefy Gerald “Slink” Johnson, Jesus walks the streets in his first century robe and sandals, but with his hair in a Tina Turner perm. Aside from the eccentric get-up, this Jesus fits right into his surroundings. He has no cash, and no place to lay his head. But that goes for plenty of Comptonites. He enjoys malt liquor and marijuana, just as much as he did good wine back in the day at Cana. He’s still preaching and practicing unconditional love, forgiveness, nonviolence, and service to all, but his street talk averages about 1.5 bleeps per sentence.

There’s plenty that’s problematic about Slink Johnson’s character. For one thing, I can’t imagine the Jesus I know using the disrespectful canine term for women so freely or being quite so nonjudgmental about the marijuana trade. But neither does this depiction approach “blasphemy,” which is what the American Family Association called it. The Catholic League, which often leads the charge against perceived offenses to the faith, got it about right when it said, “The Jesus character in this show is a mixed bag: He is irreverent and can be downright crude, but he also has many redeeming qualities.”

AS CHRISTIANS concerned about peace and justice, this time of crisis in the Middle East provides us an opportunity to return to our principles, the “springs of living waters” for people of faith:

- We need to oppose both anti-Semitism as well as any form of discrimination and racism against Palestinian Arabs. Solutions that promote or tolerate discriminatory and racist institutions and practices should be forthrightly condemned. Settlements, illegal under international law and discriminatory against Palestinians, need to be rejected rather than tolerated and legitimized.

- We need to work for justice, which requires that we work for a solution that levels the playing field rather than seek a “realistic” approach that reflects the balance of power between the parties, necessarily favoring the strong against the weak.

- We need to seek reconciliation and peace between the parties, rather than assuming eternal hostility and enmity between the parties.

My people have committed two sins: They have abandoned me, the spring of living waters, and have dug for themselves cisterns, broken cisterns ... that hold no water.

—Jeremiah 2:13

IN THE LATE 1980s and early '90s, Palestinians rose up against the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories in what became known as the First Intifada. Instead of acceding to the demands for justice by the "children of the stones," the response was a process of talks that led to the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993.

The “peace process” engaged the leadership of the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization)—then weak, corrupt, exiled, and with little vision or support—in what turned out to be a worse-than-fruitless effort that led to the perpetuation of the occupation and suffering of the Palestinian people, and which made a just peace even further away.

The process was intriguing to many of us in the peace and justice community, and it successfully co-opted us, as it co-opted the Palestinian leadership, but this process entailed both the abandoning of principled positions and the adoption of the Oslo system, a broken system that could not possibly deliver what it promised.

We were treated to a new language by Israel and the U.S., which seemed at first blush to adopt our own slogans: Where Palestinians were constantly complaining of Israel’s refusal to acknowledge them—its demonization of their leadership, and trying to have Jordan or other local collaborators speak on their behalf—the new process brazenly invited the PLO itself and its leader Yasser Arafat to participate as the “sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people.”

Saturday marked the third time since Israel began military operations in Gaza on July 8 that I let my voice be heard. I stood and marched alongside some 20,000 other individuals that like me have become utterly disgusted by what is unfolding in the Middle East.

A cease-fire has been struck, but as of yesterday, at least 1,800 Palestinians, most of whom are civilians, have been killed and nearly 7,000 have been wounded. Another 200,000 have been displaced in a territory whose infrastructure is now in ruins with mass power and water outages.

Despite the horrific events that have happened halfway across the world, the protest last Saturday, which took place at the White House, was a beautiful sight. Among the 20,000 protesters were Muslims, Jews, and Christians. There were blacks, whites, Arabs, Asians, and Latinos. There were women and men, both young and old, who had come from cities like Chicago, Tampa, Baltimore, and Boston. Many barriers were broken as we stood and marched in solidarity with the people of Palestine.

There were times when my heart was completely broken as I saw signs with photos of dead and mutilated bodies and others that listed the names and ages of children who had been killed by Israeli airstrikes. But in those same moments I would look across the sea of protesters draped in black, white, green, and red yelling phrases such as "Free, Free Palestine!" and "Stop the killing, stop the hate!" and I would once again become a prisoner of hope. I take refuge in the rock that is Christ Jesus. I know my God stands with those being oppressed, with those seeking justice and peace. I know my voice and prayers along with millions of others around the world will be heard.

Although I am pro-Palestine, that does not make me pro-Hamas or anti-Israel. I recognize and condemn Hamas's involvement in the failed peace talks and inability to find solutions. I also mourn equally for the loss of life on the Israeli side. However, despite the part Hamas has played in all of this I do not find Israel's actions to be justified. So I march.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, God calls us to love and show compassion to the stranger, particularly those who suffer. But first, they must become real to us. And there is nothing more viscerally real, perhaps, than the face of a dead child.

Is it possible to let our hearts by broken by the dead children of our enemy? Is our God big enough to allow us to imagine that God loves those we fear and despise?

Not until, I believe, they have faces.

Iraq, Syria, Ukraine, Israel, Gaza – though religious fervor is alive and well in these embattled areas, loathing, horror, and hatred seem to reign, darkness to rule. In the grim night, we cannot see each other’s faces.

The first thing that visitors and volunteers see at the Tent of Nations just outside of Bethlehem is a large stone on which are written the words, “We refuse to be enemies.” As Israeli settlements draw ever closer to their land and the Israeli Defense Forces destroy their orchards, the Nassar family continues to pay a heavy price in their practice of Jesus’ teaching, “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you (Luke 6:27-28).”

The Nassars refuse to divide the world into friends and enemies, challenging the rest of us to do the same.

As a Christian, I was raised to be pro-Israel. Since going to the region many times, I’ve become pro-Palestinian and pro-peace, too, which has led me to explore the narratives of Palestinians as well as Israelis. I grieve the deaths in both Israel and Palestine. Every human life has extraordinary value. The loss of even one life is a loss to all of us.

When the Word becomes flesh, when the Son of God becomes one who bleeds, Jesus demonstrates God's humble solidarity with human nature from Adam and Eve onward, to the last person born in history.

This vulnerability of God for us, this identification of Jesus with our collective human frailty, changes our perspective on everything. In the light that shines from the face of Jesus Christ, we at last see God and humanity with 20/20 vision.

Paul comes to this vision late in the day, well after the events of God in the flesh that reconcile the Father to God's creation. The vision of Jesus blinds him but when his eyes are healed, having seen Jesus, he sees God and humanity and the world very differently than he did before the vision of Christ that overwhelms him.

Years later, in a letter to the Corinthians, speaking about the church's worship with blest eyes he writes: "When we drink from the cup we ask God to bless, isn't that sharing in the blood of Christ? When we eat the bread we break, isn't that sharing in the body of Christ?"

The horrible human costs and increasing danger the world is now facing in Gaza, Ukraine, and Iraq show the consequences of not telling the truth. And unfortunately, we seem to mostly have political leaders who are unwilling to admit the truth of what’s happening, deal with root causes instead of exploiting symptoms, and then do everything possible to prevent the escalation of violence and further wars. Instead we have politicians who are mostly looking for opportunities to blame their political opponents, boost their own reputations, and protect business interests. As people of faith, we are called to speak the truth in love.

It’s time for some truth telling.

I was sitting in the airport the other day listening to yet another account of the current events unfolding in Israel and Palestine. Almost mechanically, the lips of the news anchor spilled out words like terrorists, extremist, escalating violence, detention, kidnapping, hatred, protest, etc. It was as though they were telling a story of some otherworldly reality that had virtually no human implications. It was all the stuff we are supposed to hear about the Middle East, so it successfully affirmed stereotypes, assumptions and prejudice.

The Presbyterian Church (USA) has removed from its website a booklet that many Jewish groups have criticized as hostile to Israel and denigrating to Judaism.

“Zionism Unsettled,” published in January by the church-chartered Israel/Palestine Mission Network, is a history and commentary on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that paints Israel as the aggressor and describes Zionism as inherently racist and theologically flawed.

The booklet played a role last month in the denomination’s debate on divesting from three American companies that, divestment proponents say, profit from Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories.