Film

The Academy Award nomination was a cause for celebration throughout the country. President Uhuru Kenyatta tweeted after the 90th Oscars ceremony in Los Angeles on March 4: “You have won our hearts as a nation … Keep telling our stories through your camera and you will win next time.”

Black youth get tired of seeing negative depictions of people of their own race in movies, said Gary, who wore a yellow and brown African dress to the movie showing. “When we found out that this was going to be an epic tale that actually was written by black writers, costumes designed by black costume designers, we were just, like, ‘We have to go see it.'"

“Where did we get this capacity to imagine that horribly complicated messes have been ironed out just because someone has looked us in the eye and told us so? I don’t know about you, but I keep getting it from the movies.” So says novelist Jim Shepard in his provocative new collection of essays on movies and making the American myth, smartly (and depressingly) titled The Tunnel at the End of the Light.

In Terrence Malick’s Badlands, Shepard sees sociopathy at the root of the desire for celebrity. He also reflects on how Saving Private Ryan was a “war movie found pleasing by conservatives and liberals, and it’s not hard to figure out why: ... more than enough war is hell to satisfy the left, and ... an even greater helping of well, it may be hell, but it sure brings out the best in us, doesn’t it? raw meat for the right.” Shepard makes a useful point— something can be remembered by one group of people as the antithesis of how another sees it.

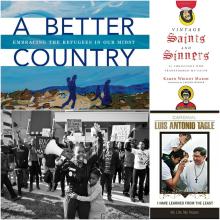

Our Streets

Filmmakers Sabaah Folayan and Damon Davis use their backgrounds as activists and artists to create Whose Streets?, a gripping documentary about the Ferguson uprising. Through scenes of hope and resistance, Whose Streets? reclaims Mike Brown’s story and shows Ferguson through the eyes of those who experienced it. whosestreetsfilm.com

We can hope, work, and pray for the day when Christians of all colors might be reconciled to one another in peace. In the meantime, Get Out reminds us that white people, especially those who claim to love us, must do better.

The Gospel isn’t simplistic, and its representations shouldn’t be, either. If The Shack were created with this creed in mind, perhaps it would be a better work of art. Instead, sadly, it’s nothing more than a religious tract.

When Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev met in what has been seen as the beginning of the end of the Cold War, the venue was an unassuming house overlooking the sea in Reykjavík, Iceland. Höfði House had been previously occupied by the poet Einar Benediktsson, who once wrote, “Take notice of the past if you would achieve originality.” Whatever else Einar meant, at this house, the necessity of learning from history can’t be ignored.

It is easier to imagine today’s enemies talking once you’ve seen the house. You see, it’s not the Avengers’ home base or one of those underground lairs favored by James Bond villains. It’s just a house, surrounded by the typical trappings of a small city—business headquarters, cafes, supermarkets. The Icelandic government uses it today for social gatherings. And what happened in it 30 years ago was at heart two people communicating, with a shared goal that transcended them both.

The notion of enemies sitting down and talking with each other is also at the heart of the magnificent new Icelandic film Rams, which I saw in a cinema about five minutes’ walk from Höfði. Two sheep-farming brothers live and work beside each other, but haven’t spoken for four decades. A family shadow has driven them apart—one of those decisions made by parents seeking the best for their children but not knowing how to arrive there. And so, separately, the brothers endure twice the hardships and experience only half the blessings of life amid this most exquisite landscape. Success is ignored by the other, or serves as an occasion for jealousy rather than celebration; Christmas is spent alone, no one to share the feast, and Icelandic winters are hardest of all.

Mel Gibson is hoping for a hit with a sequel to his 2004 blockbuster The Passion of the Christ, this time with a film focusing on the resurrection.

Gibson will direct the movie based on a screenplay by Randall Wallace, Wallace confirmed to The Hollywood Reporter June 9.

THE MOVIES AND MEANING community recently published our list of greatest films, based on the idea that in a great film the highest aims of craft and the most humane visions meet. It seeks a “third way” between one reactionary notion, that art should be judged on the basis of what it portrays rather than how it portrays it, and another—that content is morally neutral. I say bring it all: love and pain and action and laughter and grief and sex and violence and horror and contemplation. To extend Roger Ebert’s notion, a movie is not only about what it’s about, but it’s also about how it’s about it.

The most beloved films on our list include The Tree of Life (in which the most enormous, transcendent existential questions mingle with the most ordinary of tragedies and blessings), Lone Star (which aims for nothing less than the healing of U.S. memory, for survivors and perpetrators alike), and Wings of Desire, Beasts of the Southern Wild, and Spirited Away (which use magic and the supernatural to remind us of the miracle of everyday life). The top 10 also includes Schindler’s List—a testament to monstrous suffering and extraordinary courage alike—and the Three Colors trilogy, which does the seemingly impossible: take a national political virtue and fully embody it in the life of an individual.

The new version of The Jungle Book is too recent for the list and hasn’t had the chance to prove its staying power, but what a glorious surprise it turned out to be. The beloved 1967 cartoon is held in great affection, but affection that requires turning a blind eye to its colonialist and racist undertones—particularly the literal aping of some black cultural tropes by a character presented as nonhuman, whose greatest desire is to “be like you.” The 2016 version works to transcend white supremacy and even critiques human interference with the rest of nature. When a villain comes to a violent end, it’s not through the hero’s superior strength but through the bad guy’s own selfishness.

“One of the things I really see happening is as Christians in America, evangelicals are losing their cultural dominance, and I see a lot of fear associated with that. I see a lot of anger. I guess that’s almost like a god of dominance,” Midgett said. “And that’s in contrast to the god of suffering, the god who comes as a servant to die for us. Those two things are really two completely different paradigms.”

Taken purely as entertainment, Jeff Nichols’ film Midnight Special is a smart, tersely constructed sci-fi adventure in the vein of classics such as E.T. and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. That it aspires to those heights alone (and it comes very close) makes it worth seeing. But what makes Midnight Special great is that it’s also a film about belief, or the desire to believe — one that advocates for sacrificial love over fear and control, and is content with asking more questions than it answers.

EXTRAORDINARY British actor Mark Rylance has a noble theatrical reputation but has only recently found prominence in movies, most notably in the wonderful Steven Spielberg Cold War film Bridge of Spies, for which he recently won the best supporting actor Oscar. Speaking of Spielberg, Rylance made a beautiful point: “Unlike some of the leaders we’re being presented with these days, he leads with such love that he’s surrounded by masters in every craft.” This gentle wisdom—that good leaders attract good teams—echoes the message of Bridge of Spies, which illuminates the possibility of talking to each other across boundaries of militancy, misunderstanding, and fear. It is an invitation to loving leadership, criticizing a mutually destructive strategy by practicing something better.

Amid the noise of “some of the leaders we’re being presented with these days,” I’ve been indulging in a little comfort-watching, asking Charlie Chaplin to help me discern a way through. Chaplin’s brave, hilarious, and deeply moving film The Great Dictator does to authoritarianism what C.S. Lewis says the devil cannot tolerate: It mocks evil, revealing its pretensions. Chaplin’s courage has rarely been matched. Today his mantle may be held by Sacha Baron Cohen, whose trilogy of pride-puncturing, diversity-affirming films, Borat, Brüno, and especially The Dictator, is brave enough to challenge prejudice when it’s not safe to do so. These three are in the same tradition as Dr. Strangelove, In the Loop, Four Lions, Dave, and the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup, which make us laugh at the absurdity of political control, taking away some of its power.

If comic portrayals of bad leadership are comforting, serious cinematic explorations of bad leadership might help us learn how to avoid it. Nixon, Downfall, the Godfather trilogy, Citizen Kane, The Apostle, Beasts of No Nation, The Act of Killing, Leviathan, and There Will Be Blood all present warnings of what happens when leaders are self-interested, unaccountable to an emotionally mature community, and not mentored in tending to their inner lives.

WATCHING THE much-awarded film The Revenant is an ordeal, but its director Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s films have such energy and compassion that I hoped the payoff would be worth the stretch. Iñárritu’s early films Amores Perros and 21 Grams rehumanize characters who make bad choices, with an attention to scale that might be described as Napoleonic.

The Revenant is the loosely historical tale of Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio), an early 19th century fur trapper left by his companions for dead after a bear attack, agonizing his way to track his betrayer (Tom Hardy) through some of the most frozen wilderness in cinema. The commitment of DiCaprio and Hardy has been rightly applauded—this is a cold and exhausting way to make a film. And the craft is monumental—arrows seem to land on the audience, the bear attack is terrifying, the camera hardly ever stops moving. But the exploration of the futility of revenge at the heart of this story is confused.

Isn’t it time we stopped assuming every security guard, every pilot, and every lawyer on a screen should be a man? What if Hispanic women got parts other than being someone’s nanny or housekeeper? What if black women won Oscars for playing substantial characters, rather than for playing slaves, maids, or poor urban mothers?

Coming to a theater near you: the Vicar of Christ. The charismatic Bishop of Rome is set to play himself in the movie Beyond the Sun, reports Variety. This will be Pope Francis’ first time acting — not to mention the first time a pope has ever appeared in a feature film.

In marketing the film, Bay and the real-life men he portrays have stated that 13 Hours is not a political film. The goal, they say, is simply to show what happened, as it happened, and to recognize the courage and sacrifice of the people on the ground that day.

But it takes a more nuanced filmmaker than Bay (the creator of Bad Boys, Armageddon, and the Transformers films) to take an inherently political story like this one and truly make it free from bias. While 13 Hours doesn’t specifically call anyone out, or criticize (or endorse) the decisions of any particular leader or party, Bay and screenwriter Chuck Hogan mistake those qualities as the only ones required to make the film “non-political.”

For the second year in a row, every Academy nominee in an acting category is white.

Forget Idris Elba in Beasts of No Nation. Or Michael B. Jordan in Creed. Or Bernicio Del Toro in Sicario. Or Will Smith in Concussion.

The 93% White, 76% Male Academy wasn't interested.

Straight Outta' Compton was also lauded as a potential best picture nominee, but was only nominated for Best Original Screenplay, which was written by two white writers. Similarly, only Sylvester Stallone was nominated for Creed, a film with a black lead actor and a black director.

HERE ARE my picks for the best films of 2015. Honorable mentions for Creed’s operatic dignity and subtle advocacy of racial reconciliation; The Forbidden Room’s unabashed creative inspiration; Mad Max: Fury Road for being a pro-feminist action film; Spectre for James Bond going beyond an eye for an eye; Grandma, Lily Tomlin’s crowning achievement as an actor embodying that it’s okay to be different; and Room, part-thriller, part-existential exploration, honest about trauma and the lengths love will go to protect the vulnerable.

10. Shaun the Sheep. A delightfully inclusive, breathtakingly crafted story about humans, animals, and nature as one family. With frenetic comedy and an open heart, it honors the marginalized, critiques superficiality, and even lets the villain live to learn his lesson.

9. Me and Earl and the Dying Girl. An indie comedy-drama that avoids cliché and makes heroes out of nerds.

8. Beasts of No Nation. Evoking Apocalypse Now, a harrowing story of child soldiers, the legacy of colonialism, and how violence is transmitted from one generation to the next.

7. Clouds of Sils Maria. A stark reflection on identity and the conversation each of us has with the voice(s) in our head. Olivier Assayas’ film asks if we are living from the inside out or for external reward.

6. Brooklyn. A poetic and compassionate painting of the paradox of finding home as an immigrant.

Director Haynes and writer Phyllis Nagy (working from Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Price of Salt) understand that cinema, just like all forms of storytelling, is a window into someone else’s personal life. They tell the story of Therese and Carol’s relationship in such exquisitely realized detail, down even to the smallest carpet-fiber, that you almost feel as if you’re there yourself. When the world the characters inhabit feels so real, their experiences and emotions feel real, too — helped in large part by perfectly-pitched performances by Blanchett and Mara.

MICHAEL FASSBENDER'S uncanny performance as Apple Inc. co-founder and CEO Steve Jobs begs the question of how someone so clueless about human relationships could win the hearts of so many people. Of course, the performance and the Aaron Sorkin script it’s based on are not the same thing as the man himself. Steve Jobs may be unfairly treated by Steve Jobs. The question of its accuracy is not unimportant, and people who knew him deserve a hearing. But the film only sketches a persona rather than providing an encyclopedia of the soul.

Treating Steve Jobs as a film about power and personality evokes the Quaker teacher Parker Palmer’s notion of an “undivided” life. Palmer quotes Rumi’s warning, “If you are here unfaithfully with us, you’re causing terrible damage.” One facet of this unfaithfulness is the difference between living “from the inside out” and living primarily for external reward. Undivided lives are punctuated by initiatory experience, familiar to our ancestors, and now re-emerging in communities such as the ManKind Project and Woman Within. Initiatory experiences take people into the depth of their psyches, supported by wise elders, opening a crack that lets in the light of transformation. Initiated egos thrive in balanced service to the highest self and the common good (so the wise elders tell me).

The Steve Jobs in Steve Jobs has no such initiation—he seems basically the same shallow egotist at the end of the movie as he was at the start. The joy of Steve Jobs is the kinetic dance of image and sound, and actors at the top of their game (Kate Winslet as the definition of long-suffering colleague, Seth Rogen in a rare dramatic role, and Michael Stuhlbarg, all of them representing prickly conscience). The problem of Steve Jobs is that it omits engagement with the personal transformation that many think unfolded for him as his products achieved something like omnipresence. There’s no initiation here, unlike in Bridge of Spies, where Tom Hanks risks his life to negotiate a prisoner swap in a gripping, if light, Cold War thriller. Mark Rylance’s accused Soviet spy emerges more humanized than Jobs’ community-building entrepreneur.