Culture

Tired of cursing the darkness, my husband Mark and I wanted to shine a light. To do this, we set up a production company called LightWorkers Media. The Bible miniseries, born out of this intention and released last year, grew so popular that we were able to make it into our Jesus film, Son of God.

The Bible series was in its third week when Jesus began to appear on the big screen. There was great excitement that Jesus was coming, with our trailers, various talk shows and even Twitter buzzing with anticipation.

He was beautiful and strong and kind and compassionate. His presence uplifted and encouraged people. It was everything we had hoped for.

"Did you think I’d forgotten you? Perhaps you hoped I had. Don’t waste a breath mourning ... For those of us climbing to the top of the food chain there can be no mercy. There is but one rule. Hunt or be hunted." - Francis Underwood

So ends the Shakespearean soliloquy at the end of the first episode of House of Card's highly anticipated second season.

Underwood lives by a very clear code of ethics: Get to the top and do whatever is necessary to achieve that goal. For him, the end always justifies the means. And so, although it certainly made me wince to see what happens in Season 2's opening episode, I was left in awe at the show’s brutal honesty of what a life purely committed to power potentially looks like.

Some scenes perhaps strike us viewers as far from reality (Washington can't really be that bad, can it?!?), but other vignettes are far more plausible. Consider Underwood’s commendation of a congresswoman for making the cold, calculated decision to “do what needed to be done” by wiping out entire villages with missile strikes.

Her “ruthless pragmatism” merely makes Underwood smirk.

Christian leaders, including megachurch pastor Rick Warren, plan to rent every screen in numerous multiplex theaters across 10 cities for the premiere of Mark Burnett and Roma Downey’s upcoming Jesus film Son of God, on Feb. 27.

The unusual move reflects the confidence Christian leaders have in Burnett and Downey’s work in the wake of The Bible, a hit miniseries on the History channel.

The Son of God, an adaption from The Bible series, opens in theaters nationwide Feb. 28.

FOR GENERATIONS, Native North Americans and other Indigenous peoples have lived the false belief that a fulfilled relationship with their Creator through Jesus required rejecting their own culture and adopting another, European in origin. In consequence, conventional approaches to mission with Indigenous peoples in North America and around the world have produced relatively dismal outcomes.

The result has subjected Indigenous people to deep-rooted self-doubt at best, self-hatred at worst.

One of the more egregious examples of the “conventional” approach in Canada involved the church-run residential schools. Indigenous children were taken from their families, prevented from speaking their native languages, and subjected to various other forms of abuse.

Isabelle Knockwood, a survivor of church-run residential schools, observed, “I thought about how many of my former schoolmates, like Leona, Hilda, and Maimie, had died premature deaths. I wondered how many were still alive and how they were doing, how well they were coping, and if they were still carrying the burden of the past on their shoulders like I was.”

Given the countless mission efforts over the past four centuries (which in practice were targeted not so much to spiritual transformation as to social and cultural annihilation), we might conclude that Indigenous people must possess a unique spiritual intransigence to the gospel.

THIS YEAR IS shaping up to be one of enormous transition, although nothing specific comes to mind right now. I’ve just got this gut feeling. But the word that will best guide us through the coming changes may be “adaptation,” which my copy of the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines as “the process of changing to fit some purpose or situation.” My copy of the dictionary also wants me to know how grateful it is to be picked up from behind the bookshelf where it had fallen years ago. It wedged against a hot-water pipe and got kind of u-shaped.

It actually felt good to look up something in hard copy, even if the pages were warm and wrinkled. But using Google is much faster, even subtracting the time it takes to first sing the alphabet song to remind me what order the letters are in. The point is, dramatic changes will be happening to our world, and we either adapt to them or die.

Okay, maybe not die. But when Brand New becomes No Turning Back, there’s no point in resisting. This year, for better or worse, “I don’t wanna” will become “but I hadda.”

My family has already started making the necessary changes. We have no fireplace in our home, since our house was built before the discovery of fire, and thus we have no chimney for Santa to come down. But last Christmas we adapted. We hung the stockings from the microwave, then left the door open and hoped for the best.

The enclosed mall at Hillsdale Shopping Center had everything on a Friday morning: 1.3 million square feet of glistening space, top-drawer retailers like Nordstrom, reliable outlets like Macy’s, and teen-focused shops like American Eagle Outfitters.

It had everything except people.

The fabled mall — opened in 1954, enclosed in 1982 — felt like a ghost town. Or, in my frame of reference, like a big mainline Protestant church on a Sunday morning.

Bio: Carol Roth [Choctaw] is staff leader for Native Mennonite Ministries, a group that does liaison work between Native Mennonites and the broader Mennonite church. www.mennoniteusa.org/about/structure/related/

1. What are you most passionate about in your vocational role?

I’m passionate about working with the Native Mennonite people and helping them find a place in the Mennonite church. Unfortunately, some of the Native churches aren’t close to the Mennonite conferences, so you have to drive 800 miles to be connected to a conference, especially when you live on a reservation without internet or telephone. So my role is to connect the conference ministers and the conference with the Native churches and get them involved.

2. How did you come to straddle the Mennonite and Choctaw traditions?

When my twin sister and I were born [on a Choctaw reservation in Mississippi], my mom felt like she couldn’t give adequate care to two newborns. It happened that there were Mennonite missionaries who had moved nearby to help with the Choctaw group, and my parents asked if they could care for us for the winter. My parents realized how well they were taking care of us, so they asked if they could continue to care for us. My parents didn’t want them to adopt us, because they wanted us to keep our culture. So we grew up with the Mennonite missionaries, and then pretty much for all our lives attended one of the Choctaw churches.

Chiamaka tells of women who plant seeds

of peace in tribal towns, pot-banging with spoons

to call men off their game of raid-and-rape.

A girl named Hope intercepts the hands

of crowing children trading blows

and coaxes them to shake their hands

although her own are quaking. At school

my shy daughter stuffs notes in friends’ lockers,

imploring playground harmony.

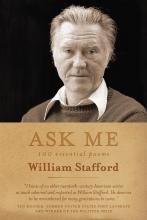

Miles of yellow wheat bend; their leaves / rustle away and wait for the sun and wind.

—From “A Farewell, Age Ten”

We wondered what our walk should mean, / taking that un-march quietly; / the sun stared at our signs—"Thou shalt not kill.”

—From “Peace Walk”

WILLIAM STAFFORD was a poet of the land and a conscience that fanned out over the land. Born in Hutchinson, Kan., 100 years ago—on Jan. 17, 1914—it was perhaps his early intimacy with space and sky that opened him to the mystery of human frailty.

At age 6, he saw two black students at his school being taunted by whites. He stood with them.

Another mystery: He who personifies the term national poet is largely unknown in his nation. Four new books (in his 79 years, Stafford published more than 50 books) published to coincide with his centennial might help redress this situation. Ask Me (Graywolf Press), from which the above excerpts are taken, brings to readers 100 “essential” Stafford poems dealing with his pacifism, his family, Native Americans, and the landscapes of his native Kansas and his adopted Oregon, where many centenary events are scheduled to take place.

INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS, the new Coen brothers film, is the mournful tale of a folk musician too dedicated to his art to make money or to accept love when it’s offered him. It has gorgeous music, performances that are like watching characters step off the pages of a Joseph Mitchell New Yorker story, and language that is exquisite, but not so much that we don’t believe it. A common response to Inside Llewyn Davis is that it’s a pessimistic film, with characters so self-centered and worn down by money and the lack thereof that they cumulatively produce a world of no hope.

Many assert that the Coen brothers have pitched their tent as the anchor tenants of cinematic melancholia—Fargo’s bleak focus is a family utterly destroyed by financial pressures and the inability to know where or how to ask for help; Barton Fink’s eponymous protagonist finds his dream writing contract ends up a descent into hell; and The Man Who Wasn’t There is finally executed because he doesn’t see the point in defending himself. Llewyn Davis is an impetuous man in a fickle industry, too out of touch with his own humanity to want to see his own child, and he is beaten up for heckling a fellow musician. And so people come out of this film depressed. To which my minority response is simple: Look closer. Inside Llewyn Davis is full of life and second chances and, yes, hope for artists. Davis has friends who care, and there are people who get what he does. Who cares if the world isn’t listening? That was never a measure of great art anyway.

IN HER LATEST book, Sara Miles—author of the spiritual memoirs Take This Bread and Jesus Freak—goes where traditional and liturgical churches don’t regularly go: into the streets to push the boundaries of public worship. City of God chronicles a day in the life in San Francisco’s Mission District, on one Ash Wednesday when Miles and others from St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church offer “Ashes to Go,” a growing national movement within the Episcopal Church to perform the imposition of ashes outside the church walls on the first day of Lent.

Ash Wednesday works on the street because it has a broad ability to speak to people with “different beliefs about God and very different relationships to the church.” Even so, carrying the observance away from the altar has generated critics. Some liturgists have wondered if, without a proper church context, “the ashes become a meaningless affirmation of our earthly life,” or whether regular folks on the street can really appreciate the profundity of the human condition and mortality without the church to explain it to them. Trusting that people on the street will “get it,” Miles embarked on a day of crossing the traditional borders of worship space to smudge foreheads in McDonald’s, taquerias, hair salons, and botanicas.

Miles finds that traditional observance of liturgies such as Ash Wednesday helps reclaim the public language of sin and repentance in a progressive way. This kind of re-evaluation of sin in common life led her to realize how she’s also fallen short of the call to solidarity and deep communion with the city. “I aspired to be the kind of neighbor who knew everyone,” she writes, “I yearned to be in real relationship.” But her admittedly self-satisfied sense of fellowship didn’t match up to her interactions. She hadn’t even bothered to learn the last name of a young Latino activist on her block and confesses, “I prayed for my neighbors, but not so much with them, and it made me uncomfortable.”

“CINEMA IS a matter of what’s in the frame and what’s out.” With this, Martin Scorsese, one of the greatest living U.S. directors, gives us a simple window to understand the power of cinema. What is in the frame is a choice by the filmmaker, and what is not highlighted is also a choice.

People of color, literally and metaphorically, have struggled to be included in the frame and fought to move from the background to the foreground of the cinematic imagination.

The U.S. cinema, historically, has been the vanguard of stereotypes and the enforcer of our racialized imagination. Our view of women, people of color, and ethnicities define and are expanded by the power of cinema.

D.W. Griffith’s 1915 silent film The Birth of a Nation was a revisionist history of the Civil War and Reconstruction that defined the Ku Klux Klan as the hero of the story and used white actors in blackface to frame black people as a threat to white society. This film, while not seen by the majority of filmgoers, set into motion the racial constructs we now view as normative. Black men, for example, have often been viewed in cinematic history as ethically dubious, highly sexualized, violent, or childlike comic characters.

These stereotypes created by the filmmaker’s imagination became, in the minds of many in the U.S., a historical fact. Cinema helped reinforce myths and arbitrary prejudices not based on cultural differences but created to protect economic interests of white Southerners who feared black labor.

Just as polar vortices sweep through America, Elsa, one of the main characters in the latest Disney princess movie, Frozen, unleashes her icy power in the fictional kingdom Arendelle, across theaters everywhere. In addition to delighting progressive audiences by satirizing Disney’s own trope of “marriage at first sight,” the story compels viewers, young and old, to find courage to be their true selves. The Oscar-nominated signature song, “Let It Go,” poignantly expresses the sentiment of letting go of fears, secret pains, and pretense. Fans of the song, from celebrities to little girls, have been belting the tune theatrically anywhere from kitchens to car rides to the Internet.

G.K. Chesterton says,

Fairy tales are more than true: not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.

A good story is more than a pleasurable experience — it empowers us to live a changed life. Frozen is filled with beloved characters and catchy melodies, but also has much to teach us about power, privilege, and community.

I noticed a loose thread in a blanket the other day and was reminded of something my mom always said: Never pull on a loose thread. All that will do is make it worse. It’ll yank on the other threads and wind up creating a knot. Even if you do manage to remove the one loose thread without doing too much damage to the fabric, it’ll leave a space that starts the nearby threads working their way loose, too.

Soon, the whole thing unravels. Removing even one thread from the fabric creates big problems.

Isn’t it the same with us?

Each of us is a thread woven into the fabric of our world. We’re looped around each other, pulled tightly to one another, intimately bound to one another. We’re so closely intertwined that we can’t be separated without making it all unravel.

By ourselves, we are a thread. Together, we are a blanket.

The weaver made it so.

In days of old, God used a burning bush to get Moses’ attention. Today’s prophets are often the truth-telling artists, singers, songwriters, and filmmakers whose modern version of “Thus sayeth the Lord” bursts forth in a stunning, sensual explosion of sight, sound, and touch.

They get our attention, and their prophetic word is visceral. It often goes beneath the rational radar and it can disturb more than it comforts. The annual Sundance Film Festival is like a tribe huddled around a campfire listening to the stories. These stories function like burning bushes, as prophetic calls to action. These films are meant not just to be watched, but to change us and, through us, to change the world.

Here are some of the messages I heard at Sundance 2014.

CNN reports on Usoni , a futuristic television drama produced in Kenya that is about reversed immigration. The show depicts Europe in 2063, where life has turned unlivable after a deadly series of natural and economic disasters.

Europeans are desperately seeking a way to get to a livable continent south of them: Africa. The hardships in making the trip are unfathomable, and once the immigrants arrive, they are unwelcome, harassed, and rejected. The story follows a young couple, Ophelia and Ulysse, who are seeking to make their way with their unborn child to the land of promise.

Yes, the comparisons today to those seeking to immigrate to Europe (with obvious parallels to America) are intentional. Marc Rigaudis, the Kenya-based French filmmaker who created the program, is making a point to help us walk in the shoes of those whom we know the Bible calls “aliens and strangers.”

The chilling trailer depicting people like me being treated as illegal immigrants is enough to make one’s hair stand on end.

Taking their cue from a tried-and-true fundraising technique, one New Jersey family tried to sell the right to name their baby.

The post on the Central Jersey Craigslist, which appeared Jan. 23, said a Jewish family had just given birth to their ninth daughter, and they were taking bids on the new name, starting at $20,000.

"This is an excellent opportunity for someone who did not have children, or someone looking to honor a relative, or even to honor someone who was killed in the Holocaust," read the ad, which has since been removed for violating the site’s terms of service.

Viewers watching the American Football Conference championship game between the Denver Broncos and New England Patriots earlier this month may have seen a Best Buy commercial for a Sharp 60-inch television that seemed ordinary, but in one way was extraordinary.

The ad shows a young, clean-shaven salesman named Mustafa talking about the television, advising customers and relaxing at home watching movies and football with his friends.

“I’m never going to get these guys out of here,” he jokes to his girlfriend at the end.

While the commercial never identifies Mustafa as a Muslim, many might assume that given his name, a diminutive for Muhammad. For viewers used to seeing negative images of Muslims on television, the commercial was a rare exception.

What if what you thought were advantages were actually disadvantages? And what you thought were disadvantages ended up being what actually makes people successful?

So embarks best-selling author Malcolm Gladwell of Blink, The Tipping Point, Outliers, and What the Dog Saw in his new book: David and Goliath. In the same clear, concise style that made his other books so intriguing, Gladwell challenges yet another widespread assumption — that being the underdog tends to make one an underdog forever.

Instead he argues that being the underdog can give one the upper hand. In his signature approach, Gladwell supports his hypothesis with a series of narratives, from the classic case of David and Goliath to the forgiveness one Canadian Mennonite woman was able to work towards after her daughter was murdered. Like his previous books, David and Goliath is both entertaining and thought provoking and obliges readers reflect over their lives and reconsider personal “disadvantages” that actually required them to learn skills they otherwise might not have had.