black lives matter

Today, we must realize that because someone is aware of the struggle for black freedom in America doesn’t mean they have been moved to action. They may have the right language — even write books, give addresses, give statements — but their actions show a commitment to the status quo rather than social justice.

“NO KNEELING!” So tweets our “dominate-the-streets” president in response to white football star Drew Brees voicing support for fellow players who take a knee during the national anthem to protest police violence. This, while demonstrations swell across the country in response to the murder of George Floyd by an officer who drilled his knee into Floyd’s neck for almost 9 minutes while the man lay face down on the ground, defenseless and dying.

Black people don’t always end up dead when encountering police. But we almost always end up wounded.

Black people have the most grace

You know why we insist that we strong

Cause for 400 years we have carried this weight

We got out okay

We are not okay

You are not okay

This is not okay

To my acquaintance, and white people who need to hear it, I say this lovingly and from a place of abundance, without scarcity: I know you are hurting too. You are human. But this is not about your pain.

Eddie Glaude has rightly named the violent White House walk to St. John’s as “dictatorial theatre.” The words that came to mind for many of us were sacrilege and blasphemy. Here's the dictionary's definition of blasphemy: "Impious utterance or action concerning God or sacred things." Another word that came to mind was authoritarian. At the epicenter of political power in the United States stands a little church that Donald Trump has decided to violently use — and now St. John’s stands inside a police perimeter surrounding that seat of power.

When the spirit came down and lit a fire in the remnant of Jesus followers on Pentecost, those followers immediately went out to the streets and protested.

Editor’s Note : Amid nationwide protests following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minn., President Donald Trump on June 1 threatened in a Rose Garden speech that he would deploy military personnel to cities that refused to call out the National Guard. Following his announcement, police dispersed a peaceful protest outside the White House with tear gas and rubber bullets so the president could cross the park and pose in front of the historic St. John’s Church. Rev. Gini Gerbasi, rector at St. John’s Episcopal Church, Georgetown, about two miles west, had been at St. John’s Lafayette Square organizing aid for protesters that afternoon. This is her account of the events.

Derek Chauvin, the Minneapolis police officer who is seen on a bystander's cellphone video kneeling on George Floyd's neck on Monday, has been charged with third-degree murder in Floyd's death, according to Mike Freeman, Hennepin County attorney.

BEFORE THEY ARE hip-hop performers, educators, and poets, the Peace Poets are a family. “It’s been a development of a brotherhood,” Frank Antonio López (aka Frankie 4) says of the group’s formation. López and Abraham Velazquez Jr. (aka A-B-E) met when they were 3 years old. Enmanuel Candelario (aka The Last Emcee) was introduced to the pair in grade school and introduced to Frantz Jerome (aka Ram 3) in high school. Candelario would go on to meet Luke Nephew (aka Lu Aya) at Fordham University in New York.

Much of the Peace Poets’ foundational development occurred in Harlem at Brotherhood/Sister Sol, a leadership and educational organization for black and Latinx youth. It was there, López says, that the Peace Poets were “politicized through art.”

IN 1983, I walked down an aisle at a Sunday evening church camp meeting in Cape May, N.J., and bent my brown knees at the altar. I had spent a year learning the basics of our faith. I had done walk-a-thons and sing-a-thons as part of a small youth group in a local Wesleyan church. I had sat through countless altar calls at Christian concerts. But now I was ready to surrender to Jesus. It was glorious when it happened: Surrendering to a relationship with him was an act of freeing myself from fear. I trusted Jesus with my life.

Freedom from fear means freedom to love—to love like the Good Samaritan loved—without limits and concern for self. This kind of love is witness. It requires belief that Jesus’ way is, indeed, the way, that Jesus’ words are the truth and will lead to good life. To love someone of another ethnicity, for example, as extravagantly as the Samaritan loved, one must believe that Jesus has got our back when we follow his lead.

ISSUES RELATED to race were at the center of my growing political consciousness when I was an undergraduate in the 1990s. Two were especially impactful: racism in the criminal justice system and racism in cultural representation.

The Rodney King beating happened when I was in high school, and there was almost nothing said about it in the largely white, professional, middle-class suburb where I grew up. In fact, the remarks that I do remember were sympathetic to the police.

The crew I ran with in college changed all that. They raised questions such as: Do you think if the officers were black and the person being beaten was white that the national conversation would be the same? Do you think that the continuous portrayals of black people as criminals had nothing to do with the acquittal of the police officers?

Those kinds of questions shifted my worldview—for the better, I believe. Given that, it should come as no surprise that the news stories I paid the most attention to in 2015 were about issues of race, the criminal justice system, and cultural representation. Basically, I was consumed with #BlackLivesMatter and #OscarsSoWhite.

There’s always been a deep tension between those who believe the powerful words about freedom for all and those who believe that such freedom should be reserved to them alone. There have always been those who believe that their personal freedom is unbreakable but the freedom of others can be rationed.

Protestors have marched the streets of downtown Pittsburgh since Rose, 17, was fatally shot three times by an East Pittsburgh police officer as he ran from a vehicle, after it was stopped by police who were investigating a nearby shooting.

In the 2016 season, many players followed in the footsteps of San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who began kneeling during the national anthem as a form of protest against police brutality and racial inequality sparking a national debate.

WITH SO MANY dust-collecting pews, judgment is not the theme on most religious leaders’ lips. The audience that took seriously the “signs of the times” is typically in nursing homes and cemeteries. Millennials and Gen-Xers find the subject distasteful at best, a fairy tale at worst. I’m not sure there’s any way to shirk the theme in this season. Judgment is on the lips of God. We better find ways to take God’s word seriously. And this word of judgment is for all people, no matter your generation.

God’s judgment is always twofold: a word against those who withhold justice and equity from communities on the margins, and a word of blessing promising those on the margins that shalom is already here and yet to come.

Still, God’s judgment is never abstract or vague; it is directed to particular people and communities. We have to search for those places in our own communities where justice and equity, where God’s shalom, is held hostage for the few.

Focused on one set of the many injustices in our world, the Black Lives Matter movement has sustained a witness for justice and equity for four years now. This movement is part of a long tradition and contemporary global movement for the liberation of black and brown lives. Calling out white supremacy is a prerequisite to taking God’s word seriously. White fragility and guilt will have to be exorcised. Black and brown assimilation to whiteness will need to be lovingly named. The vision of God’s future will keep us on this path. Our work in these weeks is continuously to call forth God’s vision of shalom for all people through the flourishing of black and brown lives.

[ November 6 ]

Resisting Whiteness

Job 19: 23-27a; Psalm 17:1-9; 2 Thessalonians 2:1-5, 13-17; Luke 20:27-38

WE HAVE SEEN some of their stories on the news and social media: Black girls, some as young as 5 and 6 years old, criminalized and harshly punished in school settings.

For example, Desre’e Watson, a Florida child, and Salecia Johnson in Georgia, both 6-year-old kindergarten students, both handcuffed and arrested by police for having emotional meltdowns—temper tantrums—at school. Or last year, the South Carolina teen flipped over in her desk and thrown across the room by a sheriff’s deputy for refusing to put away her cell phone or leave her algebra class, and, incredibly, Niya Kenny, the distraught classmate who recorded the incident on her phone and was arrested as well (though charges were later dropped).

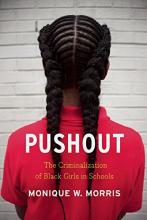

When these and other outrageous examples of harsh punishment of school children come to public attention, they are seen as part of the school-to-prison pipeline that disproportionately pushes youth of color—especially African-American youth—out of school and toward the justice system. These problems often are seen as primarily affecting males, and initiatives to address them focus on improving outcomes for black boys. In her book Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools, Monique Morris makes the case that the specific experiences and treatment of black girls in schools and society are different from those of black boys and merit systematic attention and remedies tailored to create opportunities for black girls to thrive.

Pushout examines the intersection of black girls’ experiences as both girls and black youth. The book spotlights the persistent “one-dimensional stereotypes, images, and debilitating narratives” that threaten black girls’ survival and lead them to what Morris terms “school-to-confinement pathways.” Morris, president and cofounder of the National Black Women’s Justice Institute, stresses that she is not attempting to pit oppressed identities—black males and black females—against each other. Instead, she systematically unpacks the particulars of black girls’ experiences to explain why “individuals, communities, and all sorts of institutions have an obligation to understand why the pushout of black girls ... goes unchallenged.”

Binary, Schminary

As a Caucasian who is passionate about race reconciliation, I was over-the-moon thrilled when I read the piece by Kathy Khang, “Opting Out of the Black-White Binary,” in the November 2016 issue. I have long advocated to move beyond the black-white binary, as it excludes so many others from entering the conversation or sharing their own struggles and experiences with racism. I can’t wait to share this with others or read the book she co-authored!

Shanna Seye

via email

New Life, Old Problems

The fact that only 20 percent of the members of Congress are women should be understood as evidence that women are not seen as intelligent and as capable of wise judgment as men (“Welcome to Post-Sexist America,” by Jim Rice, November 2016). Women possess intelligence and judgment because they are, like men, human persons.

A post-sexist America would reflect this truth in the make-up of our governing body. However, a post-sexist America would also be called upon to recognize and support women in the aspect of their humanity which men do not share—women’s ability to carry and give birth to new life. Yet in this matter America is woefully remiss. The United States ranks 61st in maternal health. The risk of maternal death is higher here than in any developed country. We rank 29th in infant mortality—behind Cuba. While seven babies out of 1,000 live births die by the age of 5 in America, only three babies out of 1,000 live births die in Singapore. Surely, these figures would change dramatically in a post-sexist America.

Tesse Hartigan Donnelly

Oak Park, Illinois

Why Not Pro-Love?

David Gushee’s article (“The Abortion Impasse,” November 2016) suggests that “reducing demand” for abortions is the only meaningful path forward for us. Perhaps we can expedite this as a people by reminding ourselves that the summum bonum, or “highest good,” as far as Christian ethics has been able to articulate it, is love. Not life. Not freedom. Love. The problem love recognizes is that to choose life or freedom sometimes means death to someone. Love maximizes both life and freedom and will also sacrifice both for love. We can only be “pro-choice” and “pro-life” by being “pro-love.”

Graham Hutchins

Port Angeles, Washington

God’s heart for justice

Thank you for having the courage to print Brandon Wrencher’s November 2016 “Living the Word.” I’m a 73-year-old white lady who didn’t begin to understand God’s heart for the poor, the oppressed, and justice until I was in my 40s. For about 20 years now, I’ve been sojourning mostly with black Christians, under black pastoral leadership, and studying a plethora of books by black authors. In the lives of my black friends I have seen the truths that Pastor Wrencher has brought to light. I’m praying that I can better articulate his concepts to my white brothers and sisters.

Carol Aucamp

St. Louis, Missouri

Clarification: The 1963 encyclical “Peace on Earth” was from Pope John XXIII, not from the Second Vatican Council as we stated in our December issue.

ON A SUMMER night in New York City, my husband and I enjoyed a weekend getaway. We sat atop the High Line, the elevated park along the west side of Manhattan. But our minds were a thousand miles away, in a courthouse in Florida. The George Zimmerman verdict due to come down that night was a dark cloud hanging over our date. We would finally learn if there would be justice for Trayvon. Eventually, we got our answer in the form of an iPhone news alert. George Zimmerman was acquitted.

The 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin reminded the nation that a deep racial chasm remains in the landscape of our society. The death of a 17-year-old boy carrying only Skittles and iced tea was a senseless loss. For black America, it was a sobering reminder that racism and U.S. justice are woven together so tightly that a man could shoot one of our children and be allowed to sleep in his own bed the same night.

Rest in Power: The Enduring Life of Trayvon Martin is just that, the entire story told by Trayvon’s parents Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin. In this raw and earnest memoir, Fulton and Martin allow us to come alongside them as they recall what they experienced in the days and months after their son was killed.

The sacred space of the mind in black men and women in 2018 must be reclaimed, reexamined, recalibrated, and reignited for the fight that is ours.