Arts & Culture

The contemporary Christian music industry has been adamantly opposed to affirming LGBTQ+ people. But Semler's EP Preacher's dares to include songs about queer sexuality, lesbian weddings, and Christian faith.

It’s hard to be far away when tragedy hits close to home. (Well, maybe not for Ted Cruz.)

On Feb. 16, PBS will air the first episode of a new, four-hour, two-part series, The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song. Hosted and written by Henry Louis Gates Jr., who is also the documentary’s executive producer, the series traces the 400-year-old story of the Black church in America, beginning with the trans-Atlantic slave trade and culminating in the present day.

If the empathy debate teaches us anything, it’s that for all its power, empathy on its own will not solve our problems.

Crossing a river in Africa the spider

shooting her blacksmith’s thread

of melted-down swords and armor

the world’s molten madness bridging

dangling over the water

The creature moves frantically

and to an observer miraculously

like some stressed-out downtown commuter

levitating to work

surely this is a phantasmagorical

outpouring of mighty engineering

Golden Gate sprung from a thimble

that you would never believe

if it hadn’t bored you in second grade

like the kindness of Jesus Christ

EUROCENTRIC CHRISTIANITY, since the days of Constantine, has predominately served as an apologist for authoritarian regimes, be they emperors, kings, crusading popes, or military dictators. In the last century alone, Eurocentric Christian jargon sustained and supported brutal regimes guilty of unimaginable human rights violations. Think of how the Catholic Church, fearing the loss of power during Spain’s Second Republic, threw its support behind the right-wing politics of the usurper Francisco Franco, who cloaked himself as a defender of religious liberties. The church stood by him as he ignited a civil war against the seculariziation of society, turning a blind eye to the Spanish killing fields. ...

WE ARE LIVING in dark times. A perfectly timed and distinctive new devotional, Darkness is as Light, wrestles with the dark, and from its many entries emerges a clear chronicle of the real power and meaning of God’s grace for us even—especially—in the dark.

The book consists of nine sections of eight entries each, beginning with a poem by Tennessee poet Allison Boyd Justus. Meditations by 22 authors are based on scriptural texts and grouped by theme: provision, sweetness, healing, death, balm, help, trial, consolation, and closeness. Graphic artist David Moses created striking cover art and illustrations for each section.

These are self-consciously women’s words based on women’s experiences. In her introduction, publisher and editor Summer Kinard draws connections from these modern meditations to ancient women mystics and a kind of Gothic spiritual ethos. There are occasional visions recounted in these pages, and a miracle or two, but mainly we see the range of women’s lived experiences, met every step of the way by grace. The grace of Christ shared with shunned St. Photine, the woman at the well. Ravages of bipolar disorder. Sexual abuse. Food insecurity, homelessness, inability to pay the rent. Leaving an abusive spouse. Caretaking for a chronically ill spouse. Sheltering from an abusive parent. Loss of a child. Unexpected surgeries. The exhaustion of mothering five young children.

THERE'S A TRAGIC truth behind America’s endless war since 9/11: It’s based on lies. Two recent books confront the lies. Robert Draper and Danny Sjursen independently critique the arguably the worst foreign policy blunder in modern U.S. history.

To Start A War is Draper’s account of how the second Bush administration used 9/11 to justify invading Iraq, which was not involved in the attacks. An author’s note opens his treatise: “This is a story bracketed by two defining tragedies of the 21st century. The first was an unprovoked attack on America’s homeland. ... The second, 18 months later, was an act of war by America against a sovereign nation that had neither harmed the United States nor threatened to do so.” Draper masterfully unravels the Bush administration’s litany of lies following the labyrinthine road to war from the White House to Foggy Bottom, the Pentagon, and Congress, through national security and intelligence agencies, the diplomatic corps, and military ops. The reader becomes privy to real people and conversations. Every page stirs outrage.

The end of the road? Six weeks into war, President George W. Bush swaggered across the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln, flashed thumbs up, and pronounced, “Major combat operations in Iraq have ended.” Overhead hung a red, white, and blue “Mission Accomplished” banner. Draper concludes, “The slogan accurately reflected the Bush administration’s wishful thinking and grandiose sense that history had already been made.”

IF YOU WOULD be so kind, I’d like for you to do an experiment with me. Think about a famous work of art, a painting so widely considered Important and Valuable its status could never be questioned. Maybe you’re debating between “The Starry Night” or “Mona Lisa.” Maybe you’re considering something else entirely: Monet’s endless assortment of water lilies, for example. Good. Hold the image in your mind and recall, if you can, the work’s textures, its colors and its moods. Do you like the piece? Do you remember when you first encountered it?

Now, having answered those questions, imagine that someone has stolen it. This mysterious person explains that they are holding the painting hostage until works falsely attributed to the artist in question are exposed as fraudulent. They sign their manifesto with the words, “You will come to agree with me.” What would that do for the public imagination?

Blue Balliett explores this question in her 2004 novel, Chasing Vermeer, and though its main characters are sleuthy sixth graders, I find its basic premise has much to offer even to jaded adults (see: me). A Vermeer painting on its way to the Art Institute of Chicago—“A Lady Writing”—disappears mid-journey, and the thief posits a series of challenges to art historians and the broader world. Petra and Calder, two intrepid University of Chicago Laboratory School students, find themselves caught in the painting’s thrall and, through a series of dreams and coincidences, set out to find the “Lady.” But they’re not alone.

A Shared History

Based on Andrea Levy’s novel of the same name, The Long Song depicts a young woman coming of age in Jamaica, anticipating the imminent end to slavery and her servitude. The series displays Britain’s colonial history with the island and crafts a gripping rendering of survival, insurgence, and joy. PBS.

Radical Repair

Decolonizing Discipline: Children, Corporal Punishment, Christian Theologies, and Reconciliation presents practices from Indigenous experts to repair the harm children have endured due to colonial legacies. Edited by Valerie E. Michaelson and Joan E. Durrant, this practical book reimagines raising children. University of Manitoba Press.

IN HIS BOOK Where God Happens: Discovering Christ in One Another, Rowan Williams writes, “We are easily persuaded that the problem of growing up in the life of the spirit can be located outside ourselves.” In other words, we like to think if only it weren’t for a health problem or professional situation, our lives would be better. If we put off becoming the person we are called to be because we’re waiting for the “right” circumstance, then we won’t learn and grow. Even when circumstances need to change, we must find joy in the present.

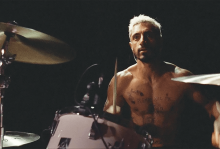

This same lesson powers Darius Marder’s drama Sound of Metal, about a drummer, Ruben (Riz Ahmed), who’s suddenly affected with permanent hearing loss. Ruben’s journey underlines the importance of presence and its potential to foster spiritual growth. He must learn that the situation he is in presents an opportunity to embrace a new community and a more intentional life.

IT'S LONG BEEN known that empathy may be inherent in portraiture—walking a mile in the shoes of one’s painting subject. As the renowned 15th-century painter and monk Fra Angelico put it, “He who wishes to paint Christ’s story must live with Christ.” New research reinforces this association between artmaking and spirituality.

A 2020 Fetzer Institute study of U.S. spirituality, which includes 16 focus groups and 26 in-depth interviews, reports that more than 80 percent of its 3,600 respondents self-identified as somewhat spiritual, and about 60 percent aspired to be more spiritual. Novelly, researchers used drawings as an “inductive research tool” to understand better what respondents meant by “spirituality,” said Veronica Selzler, lead author of the Fetzer study and strategy director at Hattaway Communications in Washington, D.C. Art allowed participants to define spirituality creatively rather than prescriptively. “It was through these drawings that the diversity and common threads began to emerge,” she said.

The study reproduced 38 drawings in which respondents, aged 18 to 71, interpreted spirituality. The “slightly spiritual/not religious at all” Dale, 69, drew five clouds—one perhaps smiling—and grass as his “happy place, but you could call it a spiritual place.” Daniel, 20, who is “very spiritual/not at all religious,” drew a self-portrait praying on his knees before Jesus.

I mispronounce my body as if

the architecture of the spine

were soft, as if this poem could

start here,

in the space between open lips,

even though it resists a title.

To be means to exist

with a name. To be means

to have a body worth defining.

I HEARD HIM loud and clear and ran as quickly as my little legs could carry me through their field, across the street, and up my driveway, straight into my house, where I hid in my room. I was seven. The very next day at school, my friend said nothing of the encounter between her dad and me. She never spoke of it, and neither did I. I, as a young brown girl, was inferior, and that white man, forty years my senior, with his shiny black gun, was superior. I would not be convinced otherwise.

After I graduated from high school, my understanding of a woman’s place in the world expanded as my grip to justice tightened, but I still held to this conscious, and subconscious, belief that if I held even a shred of power, it was because someone with privilege (in my case, white male privilege) had given it to me. Many of my pastors, bosses, teachers, and mentors, to their credit, were outrageously gracious, kind, and generous. To them I owe so much. They believed in women, married strong women, and gave me opportunities I would have never had otherwise; however, they still remained in charge of women. Many of them treated that power with the utmost respect; others abused it beyond what I could have ever imagined.

WHEN I WAS in divinity school, we had cliques. And what often separated these cliques, these little theological gaggles, if you will, was what each prized as the decisive foundation of Christian faith. For some it was scripture; for others, orthodox or anti-orthodox tradition; for still others, charismatic revelation, or the experience of the marginalized, or some cocktail of all the aforementioned. Sometimes we said Christ united us, but then we’d wonder, with charity or suspicion, “Who is ‘Christ’ to them?” Isolated on our little islands of perpetual disagreement, we nonetheless seemed secure.

In After Whiteness: An Education in Belonging, Willie James Jennings has written a love letter to theological institutions, warning against the pursuit of such security. Our knowledge of ourselves, our God, and our world comes to us creatures only in fragments, he writes, and it is in those fragments that we must always work together. Jennings weaves story and poetry to expose how the allure of “white self-sufficient masculinity” has tempted Western educational institutions, especially theological ones, to use knowledge and people to establish control in the face of fragments. Theological education may initially crack the foundations of budding ministers, but it often aims to form self-confident possessors of particular truths. This vision proceeds from whiteness, what Jennings calls “a way of being in the world that aspires to exhibit possession, mastery, and control of knowledge first, and of one’s self second, and if possible of one’s world.” Such whiteness “strangles,” he writes, “the possibilities of dense life together” for Christians.

DENNIS C. DICKERSON brings two competencies to the writing of this history. One is secular: He is a historian at Vanderbilt University, specializing in African American religious history, labor history, and the U.S. civil rights movement. The other is sacred: He is a retired general officer of the AME Church. In that capacity, he had access to the church’s extensive archives and served in the church’s leadership councils in Nashville, Tenn. With these gifts, Dickerson captures via superb research how the AME Church became a major social and denominational force in the construction of the African American religious experience — a narrative that includes the community’s enduring struggles for racial freedom, equality, and uplift. Dickerson writes:

The AME Church, located throughout its history within the Atlantic World, faced the forces of subjugation, which fixed the status of its large colored constituencies. Though AME ministers and members were themselves vulnerable peoples, they focused on the dual tasks of developing and maintaining an independent religious body and confronting powerful national, political, and economic structures aimed at black subordination. While institutional governance was itself a liberation activity, it competed and, at times, undermined equally important efforts to defeat oppressive systems of slavery, segregation, colonialism, and apartheid. The history of the AME Church is a narrative about these tensions.

IN AUGUST 2019, The New York Times published a special edition of its magazine, with an accompanying podcast, to note the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first Africans in the Virginia colony. They called the total work “The 1619 Project.” As a Times blurb for the project put it, “American slavery began 400 years ago this month. This is referred to as the country’s original sin, but it is more than that: It is the country’s true origin.”

Almost a year later, “The 1619 Project” became a school history curriculum, and in the waning days of his presidential administration Donald Trump pushed back with plans for a “1776 Commission” to promote “patriotic education” and counter the claim that “America is a wicked and racist nation.”

It’s not surprising that a nation in which everyone has a right to their own facts may end up with two foundings. However, while those who emphasize the centrality of African enslavement in the American story are certainly closer to the truth, both the champions of 1619 and 1776 are missing something crucial. For all the things it got right, “The 1619 Project” over-simplified the origins of the U.S. slave system. As the eminent African American historian Nell Irvin Painter wrote in The Guardian, “People were not enslaved in Virginia in 1619, they were indentured. The [first] Africans were sold and bought as ‘servants’ for a term of years, and they joined a population consisting largely of European indentured servants, mainly poor people from the British Isles.”

Love, Home, and Longing

Named after the hardy Korean herb, Minari follows a multigenerational Korean American family as they relocate to rural Arkansas to pursue the elusive “American Dream.” Lee Isaac Chung’s film is a stunning, visceral portrayal of creating roots of one’s own. A24 Films.

Called to Ministry

In Out in the Pulpit: The Lived Experiences of Lesbian Clergy in Four Protestant Mainline Denominations, Pamela Pater-Ennis uses theological and social work frameworks to highlight lesbian clergy, following 13 women as they reconcile their Christianity, gender, and sexuality. LifeRich Publishing.

A GENUINE HEART can overcome many a fault in the television landscape. I don’t just mean from a plot perspective, in which a character’s good nature helps them exit a situation their good nature got them into in the first place. But also from the perspective of capturing viewers’ attention—protagonists whose warmth we feel through the screen in a way that makes us forget a show’s turnoffs: occasional weak jokes, predictable storytelling, trite dialogue—all of which the Netflix show Gentefied contains.

And yet Gentefied, a half-hour comedy with a title that plays on the words gente (Spanish for “people”) and gentrified, has quickly become a favorite. The Mexican American Morales family at its center are hilarious and relatable. Casimiro (or “Pop,” as his grandkids call him), owner of a taco restaurant in LA’s Boyle Heights neighborhood, struggles to keep his establishment open as he falls further behind on its rent and gentrification makes the neighborhood less and less familiar. Meanwhile, Casimiro’s granddaughter Ana seeks to become a successful artist; grandson Chris, a trained-in-Paris chef; and other-grandson Erik, a dependable dad. Haunting their family home are Chris’ financially stable yet estranged dad and memories of Pop’s late wife. In these tough situations full of grief (Donald Trump’s xenophobic presidency does not help), Gentefied’s creators Linda Yvette Chávez and Marvin Lemus highlight the humor and love of the Morales family journey.