Opinion

Racism is on the ballot next week. Democracy is on the ballot next week. These two things two are inextricably linked because racism has disfigured American democracy from the founding of our nation. The road to a more perfect union has been long and uneven. And this road requires that we continually become a more perfect democracy and more just nation. And while our democracy will never be perfect, we must continually defend the rights, institutions, and laws that help safeguard our freedoms and advance the common good. Increasingly this election represents a test of whether we embrace and will work to realize a truly inclusive, multiracial democracy with liberty and justice for all.

Rev. Jim Wallis speaks with the founder and director of the Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life at Georgetown University, John Carr.

In the 2020 election cycle, most of the Democratic primary candidates provided videos, including Vice President Joe Biden. The Christian leaders in the Circle of Protection have asked for a video and/or statement on poverty policy from President Trump, but his campaign has not responded to repeated requests.

People of diverse faiths have a moral obligation to protect the integrity of the election. Right this minute, people all across the country are voting early or by mail, or making plans to vote in person. As religious and spiritual leaders, we are prepared to take to the streets peacefully if it becomes clear that votes are not being counted or if a legitimate election outcome is being subverted.

Dr. Frederick D. Haynes III, senior pastor of Friendship-West Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas, offers a sermon on the prophetic witness of the church ahead of the 2020 election.

Dr. Stephen Schneck, executive director of Franciscan Action Network, offers a Roman Catholic reflection on the deep, structural racism of American life. Beyond individual virtue, what is needed is political and social action to address the systemic and embedded racism in American institutions, social practices, and culture.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto, executive director of Christians for Social Action, offers a sermon on Acts 17:24-28, describing us as God's offspring. Toyama-Szeto explores this picture of a reality in which all people, made in the imago dei, are able to flourish.

"To be an antiracist church is not a political statement, it is a deeply theological Christian statement."

Techno-authoritarianism, Christian nationalism, election fairness, and other stories about things we fear and how to get us all through safely.

“God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth,” Jesus tells the Samaritan woman at the well in John 4:24. But when our worship is based in a denial of truth and runs counter to the nature and character of God is it truly worship? This is a question I have been pondering in considering a series of worship events organized by Sean Feucht, a vocal supporter of President Donald Trump, worship leader, and politician.

The work of unlearning racism and undoing our habit of exploitation — of the earth, of other bodies, and other neighborhoods — is long.

In this special SOTN episode, Rev. Jim Wallis joins Peter Eisner and Jonathan Winer, hosts of District Productive's Unconventional Threat, to discuss Lawyers and Collars, an initiative that seeks to ensure that everyone--including our most vulnerable citizens — is able to safely and effectively exercise their right to vote.

On Sunday, President Donald Trump joined a Las Vegas church service where a pastor pronounced that God told her Trump would receive a “second wind” and introduced the president against the backdrop of dancers waving American flags with the Statue of Liberty on them. On Tuesday, televangelist Pat Robertson said God told him Trump would win re-election, and it would set off a series of events ushering in the End Times.

In the midst of a tumultuous election season, Christians in the United States are discerning faithful ways to engage with politics. Christian discernment involves understanding ourselves, our relationship to God, our connection to our neighbors, and our most deeply held values.

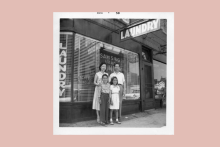

My kids are the great-granddaughters of Chinese immigrants, but until recently, I hadn’t shared much about our immigration story or been a vocal advocate for immigrant rights. Instead, like many evangelicals, I had absorbed hardline views on the subject.

Shane Claiborne offers a sermon on the peculiar politics of Christ.

The economic disparities in our country are enormous and have been built on structural racism resulting in an economic caste system. We, as citizens of the Kingdom of God, have a responsibility to steward our power to work on behalf of the most marginalized people in our country.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond , founding pastor of New Roots AME Church in Dorchester, Mass., offers a sermon on the Genesis creation story and our role in that story.

Michael-Ray Mathews' sermon is a reflection on Ephesians 6:10-19, his transformation in Ferguson, the work of racial justice, and the 2020 election.

Churches have been barred from directly supporting or opposing candidates since the passage of the Johnson Amendment in 1954. But pastors can still work on the election in meaningful ways without jeopardizing their tax-exempt status, so long as they are mindful of the rules.