We do not know how to talk about abuse – especially when the abuse is sexual, especially when the abuse happens to children, especially when the perpetrator is someone we know, trust, and love.

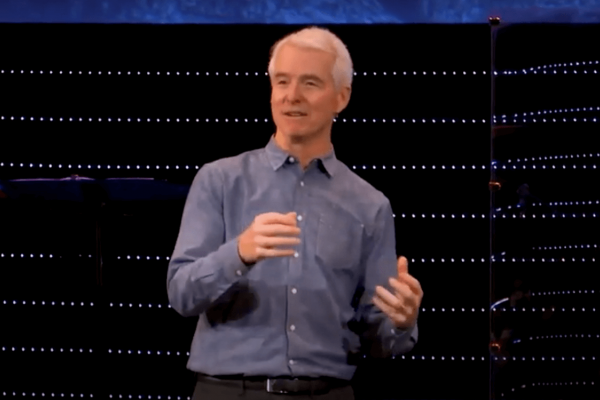

Daniel Lavery recently disclosed that his father, Menlo Church pastor John Ortberg Jr., knowingly encouraged his son and Lavery's brother, confessed pedophile John Ortberg III, to spend unsupervised time with the congregation’s children. Lavery, co-founder of erstwhile feminist darling The Toast and host of Slate’s Dear Prudence, reported his father’s negligence to Menlo Church elders in November of last year.

We do not know, nor does Menlo Church know, whether Ortberg III hurt the children whose company he craved. This question — whether Ortberg III physically or psychologically abused the children Menlo Church and his father placed in his care — matters a great deal: to the children themselves as well as, one hopes, to their families, to the congregation, to a society that claims to value the lives of children.

But Ortberg Jr.’s culpability remains the same whether his son’s violent desires were aspirational or acted upon. Ortberg Jr. does not know whether his younger son hurt children, because he did not bother to know.

Ortberg Jr. went on leave while the elders investigated Lavery’s allegations; he returned to the pulpit this March after an email reassured Menlo’s congregation the investigation failed to uncover “any misconduct in the Menlo Church community” or “any allegations of misconduct.”

Lavery says he named his brother as the volunteer Ortberg Jr. protected “in the absence of institutional accountability, so that members of the community can create a democratic, transparent process for investigating [Ortberg III’s] history of unsupervised visits to, trips with, and work involving children.” In his November 2019 letter to the Menlo Church elders, appended to his 28 June statement, Lavery implores Menlo Church staff “as much as you have loved my parents, please also hold them to account.”

We do not know how to talk about abuse, or how to reconcile our affection for abusers with the heinous nature of their deeds.

Seventy percent of all sexual assaults happen to children 17 or younger. (All statistics about child sex abuse are educated guesses; many, if not most, assaults go unreported .) Child sex abuse happens every hour of every day in every community in every state in this nation. Victims and their families almost always know the child’s assailant.

There is something ineffable about child sex abuse, something too horrific for words; as though acknowledging abuse’s occurrence and persistence — naming a person as an abuser — is somehow worse than the violation of children.

Because we struggle with how to name and analyze abuse, to reconcile ourselves to the knowledge that someone we love might also brutalize children, we too often allow abuse to go unnamed. Our silences (for they are legion) allow abuse to flourish.

We privilege our discomfort about keeping company with predators — who are also our parents, our siblings, our friends, our neighbors — over the bodily integrity and dignity of children. We would rather do nothing than protect children if protecting children requires us to disrupt our assumptions and hold abusers, whom we love, to account.

This is how abuse happens: because we let it.

Child sex abuse — and the willingness of loved ones to protect an abuser rather than address the possibility and persistence of abuse — is, as Lavery put it, “a very unique situation that happens all the time.” Lavery insisted his brother resign from all positions that gave him access to children, report his sexual proclivities to his former employers, and immediately seek therapy. Lavery and his wife Grace say they’ve received reports from Menlo Church members and that the Ortbergs “protected certain children from being alone with John III.”

Whenever I write about abuse, Patricia Lockwood’s litany resounds through my head: “Again on the altar, the mass of men moves as one body. And I chant to myself Who is protected, who is protected?”

Menlo Church and its senior pastor, John Ortberg Jr. have not protected their congregation’s children.

Feminist scholar Sara Ahmed teaches us that “when you expose a problem you pose a problem.” When we cannot deny abuse, we try to shift the narrative onto religion itself, as I argue in Abusing Religion; onto pornography; or, in the case of Daniel and Grace Lavery’s demand that the Ortbergs be held to account, onto gender difference.

While Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg calls the Laverys’ “choice to speak” “profoundly holy,” Ortberg Jr. and Menlo Church elders implied that the Laverys’ gender transitions invalidate their moral standing to demand accountability. Ortberg Jr. equated pedophila with homosexuality – implying, one assumes, that both his sons were equally culpable, equally perverse, in the eyes of God.

Menlo Church elder Beth Seabolt reassured Grace that Ortberg Jr. “loves gays and transgenders;” Grace called these “a church’s sweet words of support for queer and trans people mask[ing] a casually death-oriented fantasy” – that is, “Seabolt’s fantasy that only Christ can save queers [and pedophiles, presumably?] from suicide.” Daniel says Seabolt “responded to my [February 2020] comments by smearing me…insinuating I was mentally unstable because I am trans.” The Laverys feel Menlo Church has responded to their concerns by “covering up for its own abusers” and “smear[ing] the reporter.”

This approach, as the Laverys note, is unsurprising. We do not know how to talk about abuse, so we would prefer not to. We change the story to make the problem religion, or gender difference, or anyone who insists we hold abusers we love to account.

Abuse happens because we let it happen. The Laverys’ imperative for transparency and accountability should be the norm. It is not. Instead, their call for reparative justice met with transphobia and the risk of legal retaliation. How nearly impossible we make it to address abuse, and how easy it is to do nothing at all.

“It should not be this hard,” Daniel Lavery tweeted. “It should not take this much, or this long.”

But it is, and it does, and will continue to do so as long as we let it.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!