socialism

When President Donald Trump and New York Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani first met back in November, I had to laugh. Partially because there is something deeply absurd about these two men—Mamdani, a self-proclaimed Democratic Socialist, and Trump, who once proclaimed he wished to be a dictator for “one day”—smiling and posing for photos in the Oval Office. But I mainly found myself laughing because, despite the drastic differences between these two politicians, both have been critical to my own faith and political journey.

The term, “Black radical tradition” was coined in 1983 by Cedric J. Robinson, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Robinson saw the tradition as encompassing a host of movements — from antebellum rebellions against slave owners, to pan-Africanism, and Black Power. He defined the tradition as, “the continuing development of a collective consciousness informed by the historical struggles for liberation” in his book Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition.

In order to understand King's life and legacy, it is critical that his activism be understood in the context of his call as a minister. In 1956 a sermon titled, “Paul's Letter to American Christians,” King called for a “better distribution of wealth.” He also asserted that “God never intended one people to live in superfluous inordinate wealth, while others live in abject deadening poverty.” Holistically interpreting King’s theological work as a pastor, public theologian, and faith leader requires grounding his anti-capitalism in his self-identification as a “minister of the Christian gospel.”

Capitalism and racism are united in their reliance on hierarchies of social difference; these hierarchies act as sites of exploitation where conflicts surrounding race, gender, or even borders all reinforce our current political economy. Also, the very acts of living and working, which are structured by capital, place you in conflict with yourself and others. Everyone is impacted by the relational flow and material forms of racial capitalism. And while it is true that everyone is impacted, it cannot be understated that those who are disproportionately impacted by this system are Black and brown people.

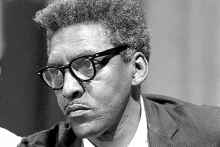

Rustin, who died in 1987, is best known for helping Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. implement Gandhian tactics of nonviolence and for the key role he played organizing the 1963 March on Washington and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference — two key components of the civil rights movement.

Less well-known are the particularities of Rustin's faith, including his deep roots in the Quaker and African Methodist Episcopal churches which drove his activism. Those two faith traditions, marked by silence and singing, respectively, echoed throughout Rustin’s life and work.

If you’ve heard white evangelical pundits lately, you’ll know there’s a dangerous “new” enemy threatening U.S. Christianity. If left unchecked, they say, this enemy will wreak havoc on traditional values and transform our entire nation into atheists. What is this growing enemy of evangelicals? Democratic socialism.

'He was of the working class and loyal to it in every drop of his hot blood to the very hour of his death.'

The emergence of Bernie Sanders as one of two finalists for the Democratic presidential nomination has renewed focus on his self-identification as a “democratic socialist.” Although several pundits, including Paul Krugman of the New York Times, have argued that Sanders’s “socialism” is really a pale version of what most Europeans regard as socialism, many Americans — including those who identify as evangelical Christians — remain suspicious of Sanders’s ideology.

For health journalist Colleen Shaddox, capitalism is incompatible with loving your neighbor.

Shall Christ or Cain reign in our American civilization?

“Socialism” is increasingly losing its status as a dirty word in the United States, especially among young people. A Gallup poll from this year reports an increase in positive attitudes toward socialism and a decline in positive attitudes toward capitalism from Americans aged 18-29, consistent with other polling trends from previous years. Though there is no shortage of Christians wringing their hands over the changing political landscape, Christians have also shown up at strikes, campaigned for candidates endorsed by socialists, and joined socialist organizations.

There are many faithful Christians who have worked for radical change in the belly of the world’s wealthiest nation long before the 2016 primaries. Their experience brings lessons and context for today’s budding movements. One of these Christians is Sister Kathleen Schultz, a Roman Catholic sister who served as the National Executive Secretary of Christians for Socialism (CFS) in the U.S. for almost a decade. At 76 years old, she remains a thorn in the side of the powerful.

THERE'S NO DOUBT that both Winston Churchill and George Orwell (two of the 20th century’s harshest critics of the Soviet Union) would be fascinated by the gaggle of money launderers, KGB men, and other Vladimir Putin supplicants dominating today’s international and domestic news.

Thomas E. Ricks, a national security adviser at the New America Foundation, has written a relatively compact dual biography of the two men, Churchill and Orwell: The Fight for Freedom. It is extremely readable, but it leaves out a lot. Ricks comments: “On the surface, the two men were quite different. ... But in crucial aspects they were kindred spirits ... [who] grappled with the same great questions—Hitler and fascism, Stalin and communism.”

It’s an intriguing thesis that in the end doesn’t quite pan out. Ricks’ narrow focus on these 20th century “isms” ignores a profound difference in attitudes by Churchill and Orwell, which in the end demonstrates a deep political chasm.

What began with a panel of organizers and activists presenting on the realities of inequality in our city turned into a community conversation led by people directly affected by pressing issues like the lack of affordable housing and low wages. The forum created the occasion for people to speak prophetically, just as it created the occasion for members of the church to hear them, to repent, and to leave changed. All of this happened because the church opened its doors to people from the outside without fear of the fact that they came with serious questions about capitalism.

We are living in a time of unprecedented economic disparity between the rich and the poor, the haves and the have-nots. Masses live in poverty so that a handful of people can live as they wish. The world’s three richest people own more than the combined economies of 48 countries. The average CEO in the US is making 400 times the average worker.

Wherever we can and whatever we do to fast from exploitative corporations on March 8 will offer incisive critiques of unrecognized labor, unfair pay, and an economy that still, 100 years later, prioritizes wealth over the wellbeing of women.

Thanks to an invite from the Vatican, Bernie Sanders will leave the campaign trail after his April 14 debate with Hillary Clinton, and fly to Rome for an event the next day at the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences.

He will gather with other world leaders to discuss changes in politics, economics, and culture in the light of Pope Francis' new encylical Laudato si', according to a statement released from the Pontifical Academy .

WRITING FOR a monthly magazine requires a long lead time. These columns are turned in several weeks before you see them, so they need to be timely, but not too timely. And that can be frustrating. But from now on, whenever I am tempted to complain about that fact of life, I will instead think of poor Michael Moore and the way current events have conspired against his latest movie, Where to Invade Next.

Way back in the 1980s, with the surprising success of his comic deindustrialization tale Roger and Me, Moore stumbled into a career as a feature-film director. But at heart he remains what he always was: an advocacy journalist. He wants to tell the story of his times in a way that will inspire people to act for change. In fact, his last job before he started making movies was a brief stint as editor of the monthly Mother Jones. Two constant themes resound through all his work, in any medium: outrage at the gross injustice of the U.S. economic and political order and faith in the capacity of ordinary Americans to change things.

But feature film is an even more unwieldy vehicle for telling the story of one’s time than a monthly magazine. The financing and logistics are byzantine and overwhelming, and the lead time is measured in years. A few times over the past three decades, Moore has managed to overcome those odds and get a message into the theaters at exactly the right time, most notably with his fall 2004 release of Fahrenheit 9/11. The national release of Where to Invade Next was scheduled for the same week as the New Hampshire presidential primary, the first primary of the season, apparently with the hope of hitting the election-year sweet spot again.

A Way Forward

Thank you for publishing Jim Wallis’ excerpt “Crossing the Bridge to a New America” in the February 2016 issue. It has injected in me some much-needed optimism and energy. The idea that racism is, indeed, America’s original sin is a powerful one that imbues in our fight against it a new hope. That we can and need to repent from this awful and systemic plague is both challenging and encouraging. With the murders of so many people of color—including Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, and Sandra Bland, among too many others—it becomes easy to slip into resigned indifference. But Wallis reminds us that we, as both a nation and as a church, need to accept and act on the truth, for it is the only way forward.

Charlene Cruz-Cerdas

Manchester, New Hampshire

The Original ‘Original Sin’

Regarding the excerpt of Jim Wallis’ America’s Original Sin in the February issue, it seems to me that our treatment of Native Americans is just as much our “original sin” as our treatment of slaves.

Anne Courtright

Pueblo, Colorado

Andrew Wilkes is an African Methodist Episcopal minister who serves on the editorial board of Democratic Socialists of America’s online journal, Religious Socialism. Danny Duncan Collum interviewed him in October 2015. Click here to read more about Christianity and socialism in this month's Sojourners.

Sojourners: Why have you chosen to identify yourself as a socialist?

Andrew Wilkes: What began to change my thoughts is when I realized that another way of organizing land, labor, and capital is possible and was already happening locally, regionally, and in some respects nationally. Gar Alperovitz’s book What Must We Then Do?, John Nichols’ book The “S” Word, and Martin Luther King Jr.’s witness of a black social gospel and democratic socialism all proved seminal to me.

What does it mean to you to call yourself a socialist? Socialism, on a basic level, prioritizes human rights over property rights and our obligations to one another over conventions about the natural, efficient operations of markets. Socialism means a way of making decisions about the use of resources that seeks to end preventable human misery more than turning an ever-increasing profit. It’s an ethical vision that also entails shared sacrifice for mutual gain—for instance, paying more in taxes to support health care, education, and other services that are free at the point of access.

I do not take socialism to mean the complete abolition of private property, contracts between individual parties, or the utter erasure of markets. Instead, socialism for me means the ascendancy of meeting human needs through public provision, cooperative ownership, and private businesses that include collective bargaining and government regulation. It also means that working individuals who produce goods and services have a significant say in shaping, owning, and influencing the institutions that shape their day-to-day quality of life.

How do you see those ideas relating to your Christian identity and Christian ministry? I joined the Religious Socialists of DSA (Democratic Socialists of America) to find an institutional outlet for my political commitments. I think it’s inaccurate to suggest that the Bible can be marshaled in direct support of socialism. I do think that every Christian has to inquire about the society that best represents or foreshadows the dreams and desires of God for humanity. For me, the kind of socialism I’ve just described is the best society.

WE NEED TO overthrow...this rotten, decadent, putrid industrial capitalist system.”

So wrote Dorothy Day, the Catholic Worker co-founder whom Pope Francis recently held up to the U.S. Congress as a great exemplar of the American spirit.

In the centuries since the rise of capitalism, millions of Christians, like Day, have sought not only to bind up the wounds of the poor, but also to create a world in which people will not be impoverished by low wages, unemployment, discrimination, or plain bad luck. Day ended up advocating a sort of communitarian anarchism. But for many other Christians—from Mother Jones to Dom Hélder Câmara to Martin Luther King Jr.—the name for that alternate system has been “socialism.” And, after long decades during which acceptance of the existing economic order seemed inevitable, in 2016 the question of socialism is not only on the agenda again but, in the Democratic presidential primaries, on the ballot.

This is especially surprising because any alternative to corporate capitalism was widely declared dead after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, which had called itself a socialist state and imposed its rule by force. Its failure, in the end largely economic, was rightly seen to discredit the Marxist-Leninist version of socialism that relied on centralized, coercive state power to manage the lives of its citizens. In the wake of the collapse, the West flooded the formerly communist states with free-market economic gurus to guide a sort of capitalist extreme makeover, and the end of history was declared.

But then global capitalism had its own collapse in 2008. In the U.S., the dream of upward mobility is dying. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, since 1973 the inflation-adjusted average hourly earnings for workers with a high school degree or less have declined; more-educated workers have barely stayed even. Meanwhile, according to the Economic Policy Institute, the inflation-adjusted income of the top 1 percent has risen 138 percent since 1979. A generation has arisen that sees its prospects declining. For this generation, “socialism” has little to do with the Soviet Union; it’s just another insult that Fox News hurls at the president most of them supported.

So for the first time in 100 years, a democratic socialist, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, is waging a serious U.S. presidential campaign. Since his campaign began, the percentage of Americans who say they are willing to vote for a socialist has risen. In fact, for the past five years, U.S. public opinion polls have shown increasingly favorable associations with the word “socialism.” Among millennials, the S-word’s positives are now higher than its negatives.

Even in the Catholic Church, consideration of socialist alternatives no longer seems taboo. Since the days of Pope John Paul II, liberation theology has been on the outs in Rome, but last year Gustavo Gutierrez, who gave the movement its name with his 1971 book, A Theology of Liberation, was welcomed to the Vatican to address a conference. This is the same man who famously proclaimed that Christian theology needs to speak “of social revolution, not reform; of liberation, not development; of socialism, not modernization of the prevailing system.”