Martin Luther King Jr.

“I do know the voice of God.”

That’s what David Oyelowo, the actor who beautifully portrays Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the new film Selma, told me last night. It’s that voice, he said, that called him to play the role.

I was at the December preview of Selma in Washington, D.C., and then took my family to see it at an early showing on Christmas day. I sometimes respond emotionally to films, but Selma made we weep. It also made me grateful that for the first time in 50 years, a big studio had finally made a film about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the people in the movement around him in Selma. I believe this movie, unlike most others, could actually change the nation’s conversation about race and reconciliation at a crucial time, perhaps even providentially.

On the premiere night, I met David Oyelowo, who spoke publically after the film about his faith. I don’t hear that kind of talk very much in D.C., but David was open and forthright, saying that playing the great Christian leader became part of his personal calling as a Christian.

In our conversation afterward, I asked David what he meant by those words. His answer prompted me to ask for an interview with him before the film, which debuts this weekend, came out. He and I talked last night (listen to the full interview below).

The shooting of Michael Brown and the failure of a grand jury to indict the shooter, Darren Wilson, are symptoms of a wider malaise.

It is part of a deep-seated illness that infects our body politic: racism.

The sad reality is that so many people believe we live in a post-racial society because we have a black president. We cannot address the issue, challenge ourselves and transform our societies without a prophetic voice. Ferguson is the space where I see that voice re-emerging into America’s consciousness.

Racism is not just about individual acts. It is about a system that allows unarmed black boys to be shot at a rate 20 times that of white boys; it allows a prosecutor to deliver a speech as a defense attorney for the accused after he fails to get an indictment. It is a system that has a black president telling people to calm down as the police, in military gear, attack them.

I SAT MY two boys down the night I got the call and heard the news. “Uncle Vincent has died and passed on,” I told 15-year-old Luke and 11-year-old Jack.

I could see the sadness in their faces. Vincent Harding had been like an uncle to them, an elder and mentor to me, a formative retreat leader for the Sojourners community, and one of the most insightful commentators and historians of the true meaning of the civil rights movement and Martin Luther King Jr.

Dr. Harding and Dr. King were friends. Vincent and his wife, Rosemarie, were part of the inner circle of the Southern freedom movement, and Harding wrote the historic speech that King delivered at Riverside Church in New York City on April 4, 1967, where he came out against the war in Vietnam and identified the “giant triplets” of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism.

That speech was perhaps King’s most provocative and prophetic address. It reflected King’s heart and mind, and went further than he had gone before in challenging foundational and systemic wrongs in U.S. life and history and not merely calling for racial integration. This King—particularly in his thinking and writing from 1964 and the passage of the Civil Rights Act until 1968, the year of his assassination—was a King perhaps best understood by his speechwriter that day, Vincent Harding.

That’s what Vincent always did for us all: asked us to go deeper into our faith.

AS AN EVANGELICAL pastor of a multiethnic church in New York City, I often find myself at the intersection of lively discussions about race. These conversations almost inevitably lead to a familiar question: What does the church do now? Maybe stated another way, “How do we work toward the dream of the beloved community?” This is why I find Edward Gilbreath’s Birmingham Revolution: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Epic Challenge to the Church to be a timely and necessary read.

While many books have been written on Dr. King and civil rights, Birmingham Revolution places King’s faith at the foreground of the writing. This is an important distinctive as King has often been co-opted, by conservative and liberal agendas alike. Yet history cannot deny that prayerful action, and a gospel that took seriously the social dimensions of human life, were at the very heart of King’s theology.

Birmingham Revolution hones in on the year 1963—a time when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference took the civil rights efforts into the bowels of structural racism. Brown vs. Board of Education had provided an important Supreme Court victory in 1954, but many forms of local resistance to desegregation prevailed in the South.

To compound the drama, many advocates in Alabama, both black and white, believed further progress should happen through legal means. They had a misplaced confidence that local structures would uphold federal law, despite the continued presence of the KKK and other such groups. Gilbreath explains Birmingham’s defining moment not only in confronting segregation, but also in challenging the subtler, unwittingly complicit voice of the moderate.

IN THE LAST YEAR of his life, Martin Luther King Jr. struggled with what are best understood as existential challenges as he began to move toward an ever-more-profound and radical understanding of what would be required to deal with the nation’s domestic and international problems.

The direction he was exploring, I believe, is far more relevant to the realities we now face than many have realized—or have wanted to realize.

I first met King in 1964 at the Democratic Party’s national convention held that year in Atlantic City—the occasion of an historic challenge by the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) to the racially segregated and reactionary Mississippi Democratic Party. I was then a very young aide working for Sen. Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin. Sen. Nelson authorized me to help out in any way I could despite President Lyndon Johnson’s effort to clamp down on the fight for representation in the interest of a “dignified” convention that would nominate him in his own right after his rise to the presidency following President Kennedy’s assassination. Johnson didn’t want a bunch of civil rights activists muddying the waters and, not incidentally, causing him problems in the conservative, race-based Democratic South.

After much back and forth, the Johnson administration offered a “compromise” proposal that the old guard be seated (provided they pledged to support him) and that two at-large representatives of the MFDP also be seated.

It may be the most famous speech of the 20th century.

Millions of American schoolchildren who never experienced Jim Crow or whites-only water fountains know the phrase “I have a dream.”

And many American adults can recite from memory certain phrases: the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s use of the prophet Amos’ vision of justice rolling down “like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream,” or the line about children being judged not by “the color of their skin but the content of their character.”

To many in this country, “I have a dream” has a place of honor next to the Declaration of Independence, the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address. It celebrates the lofty ideals of freedom.

But scholars say it would be a mistake to celebrate the speech without also acknowledging its profound critique of American values.

Don Cash had graduated from high school in June 1963 and decided on the spur of the moment to join the March on Washington when he finished his work shift at a nearby warehouse. The Baptist layman is the president of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union’s Minority Coalition and a board member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the NAACP.

“I think we got a long ways to go but I do think that there’s been a lot of changes. I don’t think you’ll ever see what Martin Luther King dreamed in reality, in total. I think we’ll always have to strive for perfection. The dream that he had is a perfect world and I think that in order to be perfect, you have to continue to work at it.”

The Dream at 50

This August marks the 50th anniversary of the historic March on Washington for civil rights for African Americans. PBS will feature special broadcast and Web programming, including the premiere of the new documentary The March onTuesday, Aug. 27 (check local listings). pbs.org/black-culture/explore

The Miracle of Meaning

Secular Days, Sacred Moments: The America Columns of Robert Coles, edited by David D. Cooper, collects 31 short essays by the respected child psychiatrist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author. Whatever the topic, Coles offers thoughtful insights on civic life and moral purpose. Michigan State University Press

The King Center is urging communities around the world to participate in a bell-ringing ceremony next month to help commemorate the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, “I Have a Dream” speech.

King Center officials say they have reached out to all 50 governors and to cities across the globe asking them to participate in the bell ringing at 3 p.m. ET on Aug. 28, or at 3 p.m. in their respective time zones.

“My father concluded his great speech with a call to ‘let freedom ring,’ and that is a challenge we will meet with a magnificent display of brotherhood and sisterhood in symbolic bell-ringing at places of worship, schools and other venues where bells are available from coast to coast and from continent to continent,” said Bernice King, King’s daughter and CEO of the King Center.

The Rev. Will D. Campbell, a Baptist minister and early white civil rights activist, as well as best-selling writer and folksy raconteur, died Monday in Nashville, Tenn. He was 88.

With a fiercely independent streak and sometimes prickly personality, Campbell used his powerful way with words to explore American racism, especially the contradiction inherent in Christian support for segregation across the South.

And he had his own contradictions, as well. A Southern Baptist who drank moonshine with the Catholic nuns he counted as his friends, Campbell was an equal-opportunity critic, castigating liberals as well as conservatives in his writing and preaching and storytelling.

BERNICE KING watched as, one by one, the heads of denominations from across the nation bent down to sign the Christian Churches Together in the U.S.A. “Response to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail.’” Transfixed, King—Martin King’s daughter—sat in the first row of a church one block from Kelly Ingram Park, where 50 years before children had run scared, ravaged by German shepherds and fire hoses.

As they signed, the presidents of CCT’s five church “families” stepped to the podium. Each read his or her church family’s confession of complicity with the demons of racism and injustice during and since the civil rights era.

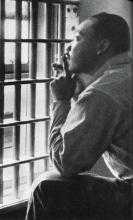

Fifty years ago, Martin Luther King Jr. sat behind bars in the Birmingham city jail and responded to criticism from eight local white clergy’s “Call for Unity” against outside agitators. King penned prophetic words in the margins of the newspaper that carried the white clergy’s call for “law and order and common sense.”

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” King explained. He recounted the failed attempts to negotiate with city officials hell-bent on living a “monologue rather than dialogue.” He clarified: “The purpose of our direct-action program is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation.”

On March 31, 1968, a few short days before his assassination, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., preached at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C.

He spoke a phrase he had used on a number of occasions and which by now, 45 years later, has gained a hard proverbial ring: "Eleven o'clock on Sunday morning is the most segregated hour of America."

The situation he described has stubbornly resisted any real movement, but the recent emergence of a radical theology dealing with violence itself is promising a crack in the walls that divide.

Black theologians such as James Cone and Kelly Brown Douglas have recognized the work of the theoretical anthropologist, René Girard. They consider it one of the few frameworks able to illuminate the nature of the violence suffered by the African-American community.

What do you say in the face of evil?

The stories from Monday’s attacks at the Boston Marathon are heartbreaking, gut-wrenching. One in particular stands out to me. A woman was waiting for her husband to cross the finish line when the bombs exploded. For three hours she searched frantically for him, not knowing if he was alive or dead, not knowing if he was frantic and looking for her. Her voice cracked and tears flowed with the raw memory as she told of the moment when she and her husband embraced.

Moments like this, even when they end happily, remind us of our vulnerability. As hard as we try to protect ourselves with heightened security measures, we know that complete invulnerability is impossible. I am vulnerable. My wife is vulnerable. My children are vulnerable. We cannot escape it.

In the face of gun violence and bombings, gender violence and rape, we would be irresponsible not to ask big questions about evil and human vulnerability.

A few hours after the bombing, President Barack Obama addressed our natural desire to carry out justice after these events.

[M]ake no mistake; we will get to the bottom of this. We will find out who did this, we will find out why they did this. Any responsible individuals, any responsible groups, will feel the full weight of justice.

Like the president, I want to take action against evil and I want to know I am secure. I hate admitting that I’m vulnerable. But the president’s words didn’t reassure me. They made me feel more vulnerable because the phrase “full weight of justice” is always a veiled call to violence.

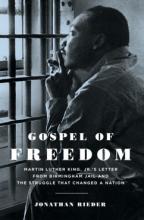

Fifty years after the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. challenged white church leaders to confront racism, an ecumenical network has responded to his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

“We proclaim that, while our context today is different, the call is the same as in 1963 — for followers of Christ to stand together, to work together, and to struggle together for justice,” declared Christian Churches Together in the USA in a 20-page document.

The statement, which is linked to an April 14-15 ecumenical gathering in Birmingham, Ala., includes confessions from church bodies about their silence and slow pace in addressing racial injustice.

“The church must lead rather than follow in the march toward justice,” it says.

A half a century after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. penned “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King’s prophetic words continue to reverberate. In “To Redeem the Soul of America” (April 2013), author and historian Vincent G. Harding recounts his time with King and explains how King’s “living letter” impacts each of us today.

Watch this video to learn more about King’s historic letter.

On Good Friday 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. led a nonviolent march through the streets of Birmingham, Ala., to draw attention to the injustices of segregation. Arrested for marching without a permit, King composed “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in response to eight white ministers who criticized the timing of the civil rights demonstrations. Rebuking the clergymen for not taking a bolder stance against segregation, King declared that “Justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

WASHINGTON — President Obama started his second term with a traditional worship service and a challenge to help heal the nation’s divides.

“We find ourselves desperately longing to find common ground, to find a common vision, to be one nation indivisible with liberty and justice for everyone,” said the Rev. Adam Hamilton, the Kansas City pastor chosen to preach Tuesday at the National Prayer Service at Washington National Cathedral. “In this city and in this room, are the people who can help.”

The inaugural service carried that theme for more than an hour, presenting the nation’s rainbow of faiths and cultures with a bilingual welcome and reading from the Gospel of Matthew, and an imam and Christian and Jewish cantors taking turns calling the congregation to prayer.

The service of petitions and patriotism included a Sikh woman calling for “concern for our neighbors” and a Catholic layman urging a remembrance of Americans’ interdependence. The red, white, and blue theme extended to the altar flowers and a worshipper’s flag-festooned headscarf.

President Obama will publicly take the oath of office on two Bibles once owned by his political heroes, Abraham Lincoln and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. One Bible was well read, but cited cautiously, the other granted scriptural sanction to the civil rights movement.

When Obama lifts his hands from the Bibles and turns to deliver his second inaugural address on Monday (Jan. 21), his own approach to Scripture will come into view. Characteristically, it sits somewhere between the former president and famous preacher.

His faith forged in the black church, Obama draws deeply on its blending of biblical narratives with contemporary issues such as racism and poverty. But like Lincoln, Obama also acknowledges that Americans sometimes invoke the same Bible to argue past each other, and that Scripture itself counsels against sanctimony.

Obama articulated this view most clearly in a 2006 speech, saying that secularists shouldn’t bar believers from the public square, but neither should people of faith expect America to be one vast amen corner.

“He understands that you can appeal to people on religious grounds,” said Jeffrey Siker, a theology professor at Loyola Marymount University in California who has studied Obama’s speeches. ”But you also have to be able to translate your case into arguments that people of different faiths, or no faith, can grasp.”

Violence does not equal power.

Martin Luther King, Jr., understood this. Yesterday was King’s 84th birthday. This year the national holiday to honor him will coincide with President Barack Obama’s second inaugural ceremony. And, all of this happens in the wake of one of the worst mass shootings in the nation’s history. One month after the shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. — which left 20 children and six adults dead, plus the killer’s mother, found dead in her home — the country grapples with the issue of gun violence. If the country is to come to consensus on the issue, we will have to distinguish between violence and power.

Vice President Joe Biden gave recommendations to the president regarding gun safety on King’s birthday. The questions the media are asking already abound: What recommendations can the president implement through executive order? Can an assault weapons ban pass Congress? Will victims and gun safety advocates be able to persuade Congress to pass meaningful legislation?

There will be varying interpretations of the Second Amendment, and there will be some who will argue that guns are necessary for self-defense. We will have the discussion as to whether or not the gun culture in the United States has taken on religious proportions.

When I stepped back and really thought about what I was experiencing on election night, I started thinking about the night of April 4, 1968, just hours after Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Having not yet been born, I thought about the coverage of it that I’ve seen. About how Robert Kennedy found himself in front of a crowd of supporters for a presidential campaign rally in Indianapolis. Many there that night were black and hadn’t heard the news of King’s death. As he did with most difficult topics, Kennedy laid it all out there. The crowd gasped and screamed and cried. Kennedy said he understood the anger and hate each of the men and women there that night would probably feel. After all, a white man had also killed his brother.

“What we need in the United States is not division,” Kennedy told the crowd. “What we need in the United States is not hatred. What we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness, but is love and wisdom and compassion toward one another. A feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country.”