Watch the segment here.

jim wallis

Forget about being a "post-racial" society. But we must learn to embrace the country's ever-greater diversity

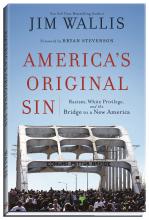

Reverend Jim Wallis joins us to discuss his new book "America's Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America".

1. What Americans Believe About Sex

A new Barna study shows the generational disparities in people's attitides about sex. “The big story here is how little everyone agrees on when it comes to the purpose of sex,” said editor-in-chief Roxanne Stone …“It’s important for Christian leaders to notice this shift in the framing of sex and to adjust their own conversations accordingly.”

2. White Christians Need to Act More Christian Than White

Jim Wallis writes in Washington Post on the need for white evangelicals to repent for how they’ve enabled racism.

The best way to change that old talk that black parents have with their children is to start a new talk between white and black parents. These conversations will make people uncomfortable, and they should. White parents should ask their black friends who are parents whether they have had “the talk” with their children. What did they say? What did their children say? How did it feel for them to have that conversation with their children? What’s it like not to be able to trust law enforcement in your own community?

JIM WALLIS’s new book is so timely that he has been wishing, for months, that he could update its pages as each new headline about racism breaks in national news.

To put this in a religious context: overcoming the divisions of race has been central to the church since its beginning, and the dynamic diversity of the body of Christ is one of the most powerful forces in the global church. Our Christian faith stands fundamentally opposed to racism in all its forms, which contradict the good news of the gospel. The ultimate answer to the question of race is our identity as children of God, which we so easily forget applies to all of us. And the political and economic problems of race are ultimately rooted in a theological problem. The churches have too often “baptized” us into our racial divisions, instead of understanding how our authentic baptism unites us above and beyond our racial identities.

Do we believe what we say about the unity of “the body of Christ” or not?

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Contact: Michael Mershon, Director of Advocacy and Communications

202-745-4654

January 6, 2016

[Editor's note: The following is an excerpt from Jim Wallis' new book America's Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America. Order your copy here.]

IN JOHN 8:32, JESUS SAYS, “You will know the truth, and the truth will make you free,” which is one of those moral statements that breaks through the confusion and chaos of our lives—untruths that we believe are able to control us, dominate us, and set us on the wrong path. Untruths are burdens to bear and even can be idols that hold us captive—not allowing us to be free people who understand ourselves and the world truthfully.

The families of the victims of the Charleston church shooting last June have spoken grace and truth, and their example could inspire us to acknowledge and change the truths about race in America. Their grace will test the integrity of our truth and our response. Will we seek, tell, and respond to the truth as we go deeper in our needed new national conversation and action on racism in America?

For example, we have seen and heard painful revelations about how police—and, even more systematically, the criminal justice system—too often mistreat young men and women of color. What happened in these incidents? And are they just “incidents,” or is there a pattern here? Is there really just one criminal justice system for all of us—equally—or are there actually different systems for white Americans and for Americans of color?

Are we hiding behind untruths that help make us feel more comfortable, or are we willing to seek the truth, even if that is uncomfortable? The gospel text cited above is telling us that only by seeking the truth are we made free, and that hanging on to untruths can keep us captive to comfortable illusions.

And if the untruths are, more deeply, idols, they also separate us from God—which is, obviously, highly important for those of us who are people of faith.

America’s foundation

The title of my new book, America’s Original Sin, is itself unsettling and, for many, provocative. We first used the phrase in a 1987 cover story in Sojourners magazine. The language of “America’s original sin” helped me understand that the historical racism against America’s Indigenous people and enslaved Africans was indeed a sin, and one upon which this country was founded. This helps to explain a lot, because if we are able to recognize that the sin still lingers, we can better understand issues before us today and deal with them more deeply, honestly, and even spiritually—which is essential if we are to make progress toward real solutions.

New York City police commissioner William Bratton acknowledged at a church breakfast in 2014 the negative role of police against African Americans throughout American history. “Many of the worst parts of black history would have been impossible without police,” Bratton said. You can imagine my surprise when he then used the language of original sin: “Slavery, our country’s original sin, sat on a foundation codified by laws enforced by police, by slave-catchers.” Bratton is no theologian or liberal academic but rather an experienced, knowledgeable, and tough cop. In fact, Bratton has been a controversial figure in New York, coming under fire for his “broken windows” policing strategy that focuses on aggressively targeting low-level offenses in order to deter more serious crime—a strategy that many say disproportionally affects people of color.

Bratton reminded fellow New Yorkers that the colonial founder of New York City, the Dutchman Peter Stuyvesant, was a supporter of the slavery system and created a police force to enforce and protect it. “Since then,” said the commissioner, “the stories of police and black citizens have been intertwined again and again.” He called the role of the NYPD sometimes “corrosive” in race relations. Bratton was talking about how the “original sin” has lingered in our criminal justice system, which is a reality that many people of color experience.

‘What do they want?’

I agree with Commissioner Bratton that telling the truth about America’s original sin is the best way to deal with it and ultimately be free of it. That makes moral and practical sense. Yet the truth of systemic injustice in the past and present must also compel us to action. It remains to be seen whether Bratton’s acknowledgment of the historical issues translates into a commitment to real and ongoing reforms in how his police do their jobs.

I DIDN'T KNOW much about sepsis until it hit me out of the blue the Friday before Thanksgiving. After working late Thursday night, I woke up the next morning shivering and shaking, with my teeth rattling and full of pain; my left leg was swollen and fire-engine red.

I was immediately sent to the hospital and told frightening things about how dangerous a septic cellulitis infection can be. The ailment is random and can strike people of all ages; bacteria gets under the skin and spreads, and if it goes into the bloodstream, things can get dangerous indeed.

I am certainly not used to lying in a hospital with intravenous antibiotics being pumped into me day and night. Fortunately, thanks to my overall good health, I responded quickly to the antibiotics, resulting in a full recovery. I’ve often visited others in hospitals and been an advocate for patients in bureaucratic health-care systems, and this unexpected visit reminded me why that is so important. It is easy to feel alone in those systems and to lose your voice. I have always been impressed by nurses, who so often bring life, laughter, and even love to health systems that so easily block out such things, and some of my nurses were the delight of my lockdown hospital time.

I grew close to my roommate in the hospital, a man who, like me, is married to an English woman, and who was clearly suffering from cardiac issues. The lack of privacy through flimsy curtains forced me to overhear a doctor telling him that he had two choices: a heart surgery that the doctor thought the man wouldn’t survive, or hospice care with only six months or less to live.

Decisions about life and death often suddenly fill these hospital rooms. My leg infection quickly shrank in comparison, and being present to my roommate and his wife became very important. Friends coming by to talk to my roommate brought tears, stories, smiles, and fears.

TWO WEEKS BEFORE entering the hospital, I had gone on a much-needed personal retreat—not to lead but just to listen, learn, and be quiet. The topics of the seminar were “character” and “gratitude.” The former was intriguing, as the subject of character always is to me. But I found the latter theme, gratitude, to be profoundly challenging—and restful at the same time. Gratitude is hard. It is especially hard for those of us who see their vocation as changing the world—seeing what is wrong and trying to make it right. We see the unjust things and want to make them just, the broken things and want to help heal them; we see the bad and want the good. It can be exhausting.

As Donald Trump continues to dominate media that try to balance a fascination for celebrities with a duty to check facts claimed by public figures of all stripes, some critics of the GOP presidential frontrunner may recall 18th century novelist Oliver Goldsmith’s line, “The loud voice that spoke the empty mind.” But a more apt thought may come from the classic 1983 movie “A Christmas Story” (airing on Turner cable networks dozens of times this week).

Remember Ralphie noticing the neighborhood bully?

Social activist, pastor and MSU graduate Jim Wallis, in a visit to East Lansing in 2006, stressed how his involvement in the university’s antiwar protests of the late 1960s changed his life.

“MSU forged who I am,” he said.

It was a turbulent era at the university, and demonstrations against the Vietnam War were a regular occurrence. Most of the campus demonstrations were heralded by simple, often hand-drawn posters that were tacked up on bulletin boards across campus, inviting students to rallies, demonstrations and marches.

It’s one of the most intriguing sub-plots of the 2016 election: Why are evangelicals, who historically have supported immigration reform and a path to citizenship for deeply felt religious and moral reasons, gravitating towards the two candidates who are most hostile to policy changes that would accommodate and integrate undocumented immigrants into American life?

Over the course of this year, there have been many moments have brought me hope. From the show of solidarity in the faith community after the terrible tragedy in Charleston, S.C., to seeing many speak out against anti-Muslim rhetoric. I’ve witnessed Pope Francis bring his message of unity and peace to America. I’ve seen young and old declare that black lives do indeed matter. And we celebrated a landmark climate agreement from the world’s leaders in Paris. I am hopeful for the future ... but only if we put out faith into action for social justice, and we need your help.

This is not the talk of charity and giving Christmas toys and turkeys to the less fortunate. The language of Mary is the narrative of revolution and redistribution, two words that the powers that be just hate. And while the revolution that Christ brings is not violent, it is nonetheless completely transformational. Mary got it.

Herod did too. The nearest political ruler to the birth of Christ immediately saw the possible implications for him.

Bryan Stevenson, the nation’s premier lawyer on mass incarceration and the death penalty, says slavery never ended. It just evolved.

I just spent two days with 50 other faith leaders at Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Ala., where Bryan emphasized four basic essentials for criminal justice reform in America: 1) Proximity to those most impacted, 2) Changing the narrative, 3) Hope replacing hopelessness, and 4) Committing ourselves to uncomfortable things, because injustice is never overcome by just doing comfortable things.

Jim Wallis is determined to bring ongoing conversations about race in America to his fellow white Christians.

“If white Christians acted more Christian than white,” he writes in his latest book America’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America, “black parents would have less to fear for their children.”

Below, you can watch the trailer for the book, which focuses on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., where hundreds of civil rights demonstrators were attacked by armed policeman in 1965.