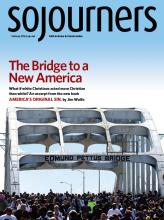

[Editor's note: The following is an excerpt from Jim Wallis' new book America's Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America. Order your copy here.]

IN JOHN 8:32, JESUS SAYS, “You will know the truth, and the truth will make you free,” which is one of those moral statements that breaks through the confusion and chaos of our lives—untruths that we believe are able to control us, dominate us, and set us on the wrong path. Untruths are burdens to bear and even can be idols that hold us captive—not allowing us to be free people who understand ourselves and the world truthfully.

The families of the victims of the Charleston church shooting last June have spoken grace and truth, and their example could inspire us to acknowledge and change the truths about race in America. Their grace will test the integrity of our truth and our response. Will we seek, tell, and respond to the truth as we go deeper in our needed new national conversation and action on racism in America?

For example, we have seen and heard painful revelations about how police—and, even more systematically, the criminal justice system—too often mistreat young men and women of color. What happened in these incidents? And are they just “incidents,” or is there a pattern here? Is there really just one criminal justice system for all of us—equally—or are there actually different systems for white Americans and for Americans of color?

Are we hiding behind untruths that help make us feel more comfortable, or are we willing to seek the truth, even if that is uncomfortable? The gospel text cited above is telling us that only by seeking the truth are we made free, and that hanging on to untruths can keep us captive to comfortable illusions.

And if the untruths are, more deeply, idols, they also separate us from God—which is, obviously, highly important for those of us who are people of faith.

America’s foundation

The title of my new book, America’s Original Sin, is itself unsettling and, for many, provocative. We first used the phrase in a 1987 cover story in Sojourners magazine. The language of “America’s original sin” helped me understand that the historical racism against America’s Indigenous people and enslaved Africans was indeed a sin, and one upon which this country was founded. This helps to explain a lot, because if we are able to recognize that the sin still lingers, we can better understand issues before us today and deal with them more deeply, honestly, and even spiritually—which is essential if we are to make progress toward real solutions.

New York City police commissioner William Bratton acknowledged at a church breakfast in 2014 the negative role of police against African Americans throughout American history. “Many of the worst parts of black history would have been impossible without police,” Bratton said. You can imagine my surprise when he then used the language of original sin: “Slavery, our country’s original sin, sat on a foundation codified by laws enforced by police, by slave-catchers.” Bratton is no theologian or liberal academic but rather an experienced, knowledgeable, and tough cop. In fact, Bratton has been a controversial figure in New York, coming under fire for his “broken windows” policing strategy that focuses on aggressively targeting low-level offenses in order to deter more serious crime—a strategy that many say disproportionally affects people of color.

Bratton reminded fellow New Yorkers that the colonial founder of New York City, the Dutchman Peter Stuyvesant, was a supporter of the slavery system and created a police force to enforce and protect it. “Since then,” said the commissioner, “the stories of police and black citizens have been intertwined again and again.” He called the role of the NYPD sometimes “corrosive” in race relations. Bratton was talking about how the “original sin” has lingered in our criminal justice system, which is a reality that many people of color experience.

‘What do they want?’

I agree with Commissioner Bratton that telling the truth about America’s original sin is the best way to deal with it and ultimately be free of it. That makes moral and practical sense. Yet the truth of systemic injustice in the past and present must also compel us to action. It remains to be seen whether Bratton’s acknowledgment of the historical issues translates into a commitment to real and ongoing reforms in how his police do their jobs.

Read the Full Article