identity

IN 2012, a group of scientists from the University of Washington discovered Y chromosomes in the autopsied brains of female cadavers. Finding so-called male DNA in cis women’s bodies certainly complicates our notions of gender! But the focus then was on introducing the sci-fi-sounding concept of fetal microchimerism. Fetal cells, we learned, can remain integrated at the genetic level in someone’s body long after the fetus or baby is not. These cells can be passed on to future siblings, thus embedding visceral relations within our bodies that even the most adept family-systems theorist would struggle to disentangle.

The scientific community labeled this a discovery. But for anyone already skeptical of the mind-body dualisms in Western culture, this was simply science catching up with how we already experience our ancestral relations. Intergenerational wisdom and trauma aren’t simply intellectual concepts. Rather, our ancestors’ presence in our lives connects at sites where body, spirit, mind, and soul inextricably intertwine. And these sites are in desperate need of some decolonizing attention if we’re to reclaim our ancestral relations in our practices of Christian faith. Of course, that might not be something we all want to do. But this month, I’ll engage the lectionary readings through this lens to see what questions and insights might arise. And I’ll do so with the hope that our wide, wondrous communion of saints will read along with us.

In Keeping Faith, philosopher Cornel West explains that our investment of “existential capital” in the nation-state leaves us with “a profound, even gut-level, commitment to some of the illusions of the present epoch.” We experience amnesia when we allow our nation’s myths to be the foundation of our current reality.

At Darbar-E-Khalsa, a large celebration of Guru Gobind Singh Ji in Southern California, I invited members of the community to tell me about their struggles and triumphs as Sikh Americans. These are their faces and stories.

Living an embodied faith asserts meaning upon our bodies both as individuals, and in relationship to one another. This means that the places our non-white bodies inhabit tell a story in itself, just as God enfleshed “entered our lives, calling us from the tomb in which society has sought to confine us.” The shared space of believers living out the Christian faith in diverse, multi-ethnic communities is a witness to our world of the power of Jesus Christ.

I'M HIGHLY SUSPICIOUS of the growing obsession with genetic ancestry tests. 23andMe. AncestryDNA. People can now scrape their inner cheek with a swab, mail it to a company for $99, and brag to you about a cultural or racial epiphany they’ve had based on being 4.7 percent of something. Who knows how this personal genetic information might be used. I suspect these companies respect people’s privacy as much as Facebook does. I’ve heard that governments and police departments are already using this information to track people.

And yet, I would be lying if I said I haven’t thought about purchasing a DNA kit for myself. Yes, I know that such tests provide limited and potentially misleading information. Yes, I understand that they fuel problematic framings of race that tie race to genetics when race is actually something socially and politically constructed. But I’m still curious!

I don’t know if I will ever take a test. I ask myself: Should I be contributing to this system? Could I convince Sojourners to pay for my test if I were to write an article about it, thus shifting some of the ethical burden away from me as an individual?

TO LIVE A LIFE of justice, we must also live a life of constant self-reflection. My work as a writer, activist, and woman of faith informs my actions in matters of justice, which I call soul work. Yet, if I cannot examine the ways I am complicit in oppressive structures, I become part of the problem. I never want to assume that my justice work, my soul work, is not in need of introspection.

I learned about spiritual activism from reading AnaLouise Keating’s scholarship of Gloria Anzaldúa’s theopoetic work, which focuses on navigating between spaces such as home, language, the academy, gender, and spirituality, among other conceived and imagined spaces. A theopoetic work wrestles with the tension of in-between spaces when theological language fails us and we must instead take up a form of spiritual activism—advocating for our own inner healing while addressing the injustices of the world.

IN ITS THIRD chapter, Hermanas asks: “What is your beautifully empowering narrative that may influence your hermanas [sisters] around you and those that are to come after you?” In the most wonderful way, the book’s three authors—Natalia Kohn, Noemi Vega Quiñones, and Kristy Garza Robinson—share their own stories to answer this essential question. Through the writing, they become the Latina mentors and role models many Latinas want and need, as many of us have no such examples in our communities.

What comes through these pages is how much these writers embrace their identities as Latinas, how much they love their communities, and how deeply they’ve experienced God through their identities.

They rightfully make no apology for writing this book for the many Latinas that may have had similar experiences with dominant white Christian culture. They read, interpret, and apply the Bible from the perspective of not just Latinx culture, but the specific experiences of Latinas who often find themselves doubly marginalized by racism and sexism and, thus, unheard. The authors provide examples of biblical women such as Esther, Deborah, and Hannah who embrace their ethnicity and challenges to become leaders and teachers in their spheres of influence, whether directly or indirectly.

Following up with Juan after a year of struggle in the wake of the storm, he said, “Puerto Ricans are proud, committed, strong, and ‘pa’lante’ (moving forward). And that includes Muslims.” After the destruction of Hurricane Maria, the month of Ramadan, held special meaning for him. It held hope for “renewal.”

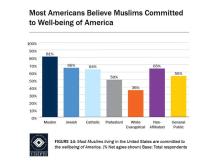

“The vast number of Muslims say being an American is important to how they think of themselves,” said Dalia Mogahed, director of research at the ISPU. “They also say that being a Muslim is important to how they think of themselves. When you look at those identity factors, they’re actually mutually reinforcing — meaning, if you have a higher Muslim identity, you are actually more likely to have a stronger American identity. They’re not in competition.”

Morrison’s wisdom and her immense love for blackness — a heritage, but also a color often used to describe evil and evoke disgust — have been blessings to the world for almost half a century. She has written and published eleven novels, numerous children’s books and nonfiction books, two plays, a libretto for an opera, and despite being 87-years-old, she shows no signs of stopping.

RECENTLY, a Facebook troll accused me of liking country singer Carrie Underwood. The troll was ... me.

“I hate to admit it ... but in the interest of full disclosure, I kind of love Carrie Underwood’s ‘Cowboy Casanova,’” said 23-year-old me. Real-time me was horrified.

The indignities kept coming. College junior me: “I was impressed by Mike Huckabee and Ron Paul,” after a GOP debate in South Carolina in 2008. ( Mike Huckabee?!) College senior me, more inscrutably, presumably comparing President Obama’s first inauguration to Woodstock: “Back from Obamastock, living the dream.”

Of all the ways to be internet shamed, I hadn’t counted on my old selves.

Launched in March 2015, Facebook’s feature On This Day collects every status update and photo users have shared on that day, every year, all the way back to the beginning of (Facebook) time.

For a social platform, this function is oddly, endearingly private. Newsfeed and Pages and Groups are where we meet others, but On This Day is where we meet ourselves. The for-your-eyes-only digital diary delivers a daily string of our admissions from years gone by, betting on our appetite for nostalgia and navel-gazing. Sometimes, reading the morning roundup delivers an ego boost. (“I was funny!” I once announced to an empty home.) Other times, I’ve shared things that my present self flat-out refuses to believe.

Facebook is 12 years old and has been with me longer than most close friendships in my life. And it acts like it: On This Day is a best friend eager to remind me how desperately, and how often, I’ve tried to be cool. But it also reflects me at my most earnest, filled with unselfconscious observations on life and tentative explorations into new ideas of justice, identity, and belonging.

I WAS RAISED in an African-American church, but as an adult I discovered Anabaptism. Since then I’ve sought to learn from both the wider black church and Anabaptist traditions, to the point that I now consider myself an “Anablacktivist.”

Two experiences at my undergraduate Christian college helped propel me to see the significance of these two Christian streams. The first time was a chapel service, maybe a year after 9/11. The speaker, the Catholic priest John Dear, challenged us about U.S. violence and militarism—arguing that these weren’t consistent with the life and teachings of Jesus. I leaned forward in agreement, captivated by his message, feeling that it rang true and faithful to Jesus.

Then I noticed some movement in the darkened auditorium. Droves of students disruptively got up from their chairs and headed straight for the exits, in protest of the speaker and his “subversive” message that refused to affirm everything that the U.S. was doing in the world. I found myself deeply troubled by the defensive response of my (mostly white) Christian brothers and sisters to Dear’s thoroughly Jesus-shaped critiques of U.S. empire.

Some of you may know the experience of having a secret about yourself that when revealed makes you have to completely reframe your identity. This happened for me in my junior year of high school when I was offered the opportunity to travel through a college bound program. That is when I learned I was “undocumented.” The reality of the broad impact of this label set in with each evasive answer my mother gave when I asked if I’d be able to not only travel, but drive, or work to help pay the bills. Being undocumented threatened my dreams of going to college; it threatened the possibility of a better future.

I was born in Mexico, and as proud as I am about my ethnicity, there is only one place I know as home, the United States. My father abandoned us when I was 3 years old and this set everything in motion that would lead me and my family to the U.S. When we struggled without his support, my older brother left for the U.S. in search of a better life at the age of 14. My mother’s love for her oldest son drove her to leave her home as well. When my brother learned she was considering leaving me, his young sister, in the care of my uncle while she visited him, he insisted she brought me along. I have now been in the U.S. for 25 years.

I grew up with music in my life. At first, it was a combination of my dad’s Willie Nelson and Ray Charles with my mom’s old southern Gospel hymns. I’d sit under the piano, feeling the vibrations as she played “Blessed Assurance,” and then lie on the floor in front of the speakers as Ike and Tina belted out “Proud Mary.”

And then I discovered my own music, in the form of rock. Eventually, I sang lead in several hard rock bands around Dallas hitting all the local hot spots and singing until I was hoarse and exhausted. It was during my decade away from church that I did most of this, but I didn’t realize until recently that, despite the pretense of countercultural rebellion the music offered, it actually gave me some of the same things I experienced as part of organized religion.

Of course, only the most uneducated would think of rock music as some monolithic think that was barely held together by the pursuit of sex, drugs, and fame. There were rules. There were codes. And my lord, there were categories.

Any time you asked a band what style they were, inevitably they’d sigh and equivocate, finally listing off a handful of bands they most certainly were not like. No one wanted to be categorized, and yet we were more than ready to label all others and fit them in to their neat little musical denominations.

The top religion story of 2012 was the “rise of the ‘Nones’” — the one in five adults in the U.S. eschewing any religious label. That trend is now evidenced across the American religious spectrum, including in Jewish communities. About 22 percent of Jews now describe themselves as having no religion, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of U.S. Jews.

“Fully a fifth today of Jews in the United States are people who say they have no religion. They’re atheists, agnostics, or, the largest single subgroup, nothing in particular,” said Alan Cooperman, co-author of the study.

The trend of disaffiliation mimics that of other backgrounds, particularly by age. For example, 93 percent of Greatest Generation Jews (those born between 1914 and 1947) identified as being Jewish by religion, while only 68 percent of Millennial Jews (those born after 1980) say the same.

FOR ANYONE who’s sick of explaining that not all evangelicals are flag-waving, Quran-burning, gay-hating, science-skeptic, anti-abortion ralliers, The Evangelicals You Don’t Know: Introducing the Next Generation of Christians provides a boost of encouragement. Written by frequent USA Todaycontributor Tom Krattenmaker, this who’s who of “new-paradigm evangelicals” explains how a growing movement of Jesus-followers are “pulling American evangelicalism out of its late 20th-century rut and turning it into the jaw-dropping, life-changing, world-altering force they believe it ought to be.”

Unlike their predecessors, these new evangelicals are characterized by a willingness to collaborate with members of other religions and no religion for the common good, warm acceptance of LGBTQ folks, a rejection of the dualistic pro-life vs. pro-choice debate, and a desire to participate in mainstream culture rather than wage war against it. All this “while lessening their devotion to Jesus by not a single jot or tittle.”

Admittedly, the book’s cover photo doesn’t quite do justice to Krattenmaker’s observations. Featuring young worshipers in a dark sanctuary with hands uplifted and eyes closed, each apparently lost in a private moment of four-chord progression praise, the cover looks more like a Hillsong worship concert circa 1998 than cutting-edge 2013 evangelicals. (If you’re unfamiliar with the four-chord progression, Google “how to write a worship song in five minutes or less.” You’re welcome.)

"EVEN IF I OWNED Picasso's 'Guernica,' I could not hang it on a wall in my house, and although I own a recording of the Solti Chicago Symphony performance of Stravinsky's 'Rite of Spring,' I play it only rarely. One cannot live every day on the boundary of human existence in the world, and yet it is to this boundary that one is constantly brought by the parables of Jesus." So wrote a great New Testament scholar, Norman Perrin, in his book Jesus and the Language of the Kingdom. I often think about his frankness as I prepare for the transition between Epiphany and Lent. We must soften and make bearable the intensity of the scriptural story to face it every week in church. We can't dive to the depths every single week, and we are right to keep our child-friendliness going.

But we need to risk depth and passion, or run the danger of making the gospel seem boring and predictable. Our churchly betrayal of God lies in our willingness to make the Word seem banal. So perhaps the thing we need to give up for Lent is our avoidance of depth. The scriptures this month will speak to us of faith as the experience of being stressed almost to a breaking point. They will plumb the depths of divine frustration and disappointment. We must clear a space for these wounding and thrilling themes and suspend our strategies for making worship palatable and safe.

NICK HARKAWAY’S second novel, Angelmaker, is out now through Knopf. His first, The Gone-Away World, found favor with fans of boisterously literate science fiction. Angelmaker is, in many ways, tipped from the same mold as its predecessor. It is unapologetically fun (with a particularly English sense of humor familiar to fans of Stephen Fry and Douglas Adams), stuffed full of blisteringly creative ideas and digressive subplots, and shot through with darker undernotes. In it Harkaway asks some large questions about (among other things) the nature of identity, who owns the truth, the dark side of the will to power, and the true cost of the preservation of stability. The novel also makes a strong case for the power of compassion, courage, and the glory of imagination used well.

Angelmaker follows two alternating threads. In one an irreverent and intelligent orphaned girl, Edie Banister, is recruited into wartime secret service with the Ruskinites, an order of men and women devoted to beautiful craftsmanship who have been roped into weapons development. She rescues and falls in love with a genius who is using microscopic clockwork to build a supercomputer that will reveal the truth and end war. This “Apprehension Engine” (the titular Angelmaker), is baroque and bizarre; the force field of truth is to be disseminated by mechanical bees swarming from clockwork hives around the world. Naturally, an unreconstructed dictator wants to use it as a weapon of mass destruction.

The second thread is the present-day tale of Joe Spork, as he attempts to lead a humble, honest life until he is manipulated into adventure by the elderly Banister and pursued by the now-corrupt and terrifying Ruskinites.

Pariah, written and directed by Dee Rees. Focus Features.

NEW YORK — Did leaders of the Southern Baptist Convention hurt their missionary cause by opting not to change the denomination's name to something a bit more, well, marketable?

Maybe, but as the advertising executives of Madison Avenue here could attest, as tempting as it is to try to solve a missionary slump with a marketing campaign, religious groups — like commercial businesses — should think twice before undergoing a brand overhaul.

After months of deliberations, an SBC task force on Feb. 20 recommended against trying to re-brand the denomination, an idea that has been bandied about for more than a century.

Proponents of a change made a good case: for a denomination that was born in 1845 out of a defense of slavery, the name has since saddled Southern Baptists with a problematic name and historical baggage.