Books

Children's literature provides one of the most uplifting, energizing, and soul-freeing pursuits for any child-or any adult who cares about children.

In Disciples of the Street, Eric Gutierrez weaves three storylines into a narrative about the role of hip-hop in Christian ministry.

Some—okay, a lot—of science fiction treats religion, and even spirituality, as pre-rational claptrap or dangerous authoritarianism. But jostling on the same shelves as the neo-imperialist space wars and the vampire-themed soft porn, there’s a universe of spiritually relevant good writing. Some examples from the last decade:

Eifelheim, by Michael Flynn

When a starship full of insectoid aliens crash-lands in a German village just before the advent of the Black Plague, the author gives credit and care to the parish priest’s training in logic, to Christian caritas, to the 14th-century European political and intellectual landscape, and to how they might interact with giant grasshoppers from space. (Tor, 2006)

Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents, by Octavia Butler

In response to a near-future U.S. wracked by environmental and social breakdown, young Lauren Olamina starts her own religion, Earthseed, whose scriptures proclaim that “God is change” and that humanity’s destiny is to reach the stars. Her vision leads her into deep family complications, somewhat manipulative behavior, and multiple run-ins with the nasty Church of Christian America. (Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993; Seven Stories Press, 1998)

God is in the details—or is it the devil? Authenticity certainly lurks there, which is abundant in the best fiction. Uwem Akpan understands this. When writing about Rwanda, he wanted to get the details right. Marriage customs, traditional dress, the color of the earth—the small, everyday matters that make a story come alive and that inhabitants of a place will spot right away if a writer gets it wrong. So Akpan attempted to travel to Rwanda for research.

But his superiors wouldn’t let him take the trip—they preferred that he remain at his seminary in Kenya. He was resigned to asking questions of his Jesuit brothers in letters and e-mails, and left to imagine Rwanda’s earth.

Akpan is most likely the first Nigerian Jesuit priest to have two stories published in The New Yorker, that Holy Grail for short story writers. “An Ex-Mas Feast” and the Rwanda story “My Parents’ Bedroom” are both featured in his first collection, Say You’re One of Them, published last June by Little, Brown and Company. In two novellas and three stories, he juxtaposes startlingly lucid writing and imagery with nearly unspeakable situations—child trafficking, genocide, religious and tribal divisions and violence, and desperate poverty. Each of the stories takes place in a different African country, and all are told through the perspectives of children.

Here’s the voice of 8-year-old Jigana at the opening of “An Ex-Mas Feast”: “Now that my eldest sister, Maisha, was 12, none of us knew how to relate to her anymore. She had never forgiven our parents for not being rich enough to send her to school.”

Song for Night, by Chris Abani

A 15-year-old boy named My Luck, a human mine detector in an unnamed West African war, wakes up to find he’s been separated from his platoon. He can’t speak—like his comrades, his vocal cords have been cut so that if a mine explodes, they won’t be heard screaming—but his journey through the physical and emotional wreckage of war, which include his own deadly actions, is eloquent and heartbreaking. “[E]ven with the knowledge that there are some sins too big for even God to forgive,” he thinks, “every night my sky is still full of stars; a wonderful song for night.” (Akashic Books, 2007)

The Inheritance of Loss, by Kiran Desai

The action moves between northeast India—where a retired judge, his orphaned granddaughter, and their England-loving neighbors live near the borders of Nepal, Tibet, and Bhutan—and New York, where a cook’s son lives the terrifying life of an immigrant. All of Desai’s characters struggle in deep and painful, yet often funny, ways with the forces of colonialism, globalization, and modernity. (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2006)

The upcoming presidential election wraps up months of campaigning, in which each political party has tried to outdo the other in its public storytelling. The narratives follow familiar terrain: “We are the party of change,” says one. “We will keep America strong,” says another. Each party has spent millions to present its candidate as the true “outsider” to Washington politics, the honest crusader who can fix what’s broken in America. These storylines are carefully crafted to appeal to our ideals and our frustrations—in short, they tell us what we want to hear.

Leaders the world over use their power to shape narratives—to good and bad effect. Under repressive governments, such as in China or under South Africa’s apartheid regime, storytellers of a different kind—writers—are among those who suffer when their work doesn’t conform to prevailing social, political, religious, or cultural narratives. Their work is banned, they are silenced, put in prison, exiled—or worse. Unlike politicians, writers often tell their governments, and us, what we don’t want to hear.

The death of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn earlier this year reminds us of the powerful impact of his One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. This slim volume penetrated the silence of the Stalin-era Soviet Union by telling the story of Ivan Denisovich Shukov, a peasant imprisoned in a Siberian concentration camp. Solzhenitsyn—who spent eight years in similar camps himself—describes Ivan’s day, from morning reveille to evening bedtime, as he follows the petty, arcane rules of staying alive. This tiny revolution of words allowed the world to see what happened to those on the wrong side of Soviet power. For his efforts Solzhenitsyn was exiled, but not stopped; his three-volume indictment of the Gulag system, The Gulag Archipelago, was published about 10 years later.

For 500 years, Western culture, for better or worse, was formed by its books. Great novels have held up a mirror to the foibles and absurdities of human nature, while book-length manifestos have set the terms of political debate and social struggle (think Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, Marx’s Das Kapital, or even Hitler’s Mein Kampf).

For decades now, we’ve heard predictions that a culture founded upon the book is on its way out. The electronic culture ushered in by TV and confirmed by the Internet, we’ve been warned, would eventually render most people incapable of the kind of concentration required to really inhabit a serious book. Teachers have regularly reported a decline of interest in reading among the coming generations.

Despite these warnings, the book publishing industry marched on. Book sales kept rising. Sure, sales figures were pumped up by relentless niche marketing, fad-pandering, and Hollywood tie-ins. Still, books were moving off the shelves. But now the declining importance of print has begun to show up on the bottom line. According to a report by the Book Industry Study Group, in 2007 overall book sales barely increased at all, and would actually have declined if not for a single title—the final installment of the Harry Potter series. Publishing giants, such as Random House and Simon & Schuster, are showing declining incomes. Meanwhile, sales of books for young children are declining, which confirms the common-sense impression that, with each passing year, the place once occupied by books and reading is being filled by electronic gadgets with hypnotizing screens.

Mary Doria Russell’s science fiction books The Sparrow and Children of God put Jesuits in space and wrestle with the missionary issues of first contact. She’s gone on to write historical fiction, including A Thread of Grace, which tracks the underground efforts of Italians to save Jews during the final phase of World War II, and Dreamers of the Day, which explores the 1921 Cairo Conference through the perspective of an Ohioan woman caught up in forces that would shape the modern-day Middle East. Now Russell has jumped genres again and is writing a murder mystery/Western set in Dodge City, Kansas. Sojourners associate editor Rose Marie Berger interviewed Russell, who lives in Cleveland, this summer by e-mail.

Rose Marie Berger: How would you describe your spiritual journey?

Mary Doria Russell: Hardheaded. Pragmatic. Poetic. In that order!

How has your understanding of God changed over time? In 1955, the kindergarten kids at Pleasant Lane School in Lombard, Illinois, were told to bring in “something that is important to you” for show-and-tell. I remember this very clearly. A devout Catholic at that age, I arrived with a milk-glass statuette of the Virgin Mary and told the class that she was important to me because “she was the mother of God, and if it weren’t for her, there’d be no God, and then there’d be no world.”

Simply speaking those words aloud got my 5-year-old self thinking about the logical and sequential questions that statement begged. I became a more sophisticated Catholic as I matured, but eventually the theological package linking the Trinity, original sin, divine incarnation (with or without virgin birth), and salvation through blood sacrifice lost all credibility for me.

[Continued from part 1] I began to wonder what the TBN folks would think of me, a heavily tattooed Christian progressive from a liturgical denomination. How would people in their theological camp respond to my preaching? Would they think, as I do of them, that I misuse scripture?

To say that Christian television is "not my thing" doesn't even get close.

This summer, two friends and I are doing something that seems a bit outlandish (especially for 40-year-old guys). We've borrowed a friend's RV, and we're touring the country to talk about our books. Doug Pagitt (A Christianity Worth Believing), Mark Scandrette (

This summer, two friends and I are doing something that seems a bit outlandish (especially for 40-year-old guys). We've borrowed a friend's RV, and we're touring the country to talk about our books. Doug Pagitt (A Christianity Worth Believing), Mark Scandrette (

Some fun for your Friday: Mark Pinsky, author of The Gospel According to the Simpsons, has reviewed the newly released

Some fun for your Friday: Mark Pinsky, author of The Gospel According to the Simpsons, has reviewed the newly released

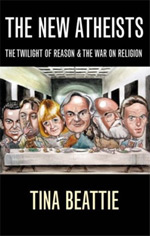

Becky Garrison recently e-mailed Tina Beattie, author of

Becky Garrison recently e-mailed Tina Beattie, author of