But evangelical leaders are stepping forward. They are voicing support for the structural and systemic protection of the image of God in black people. And as in the days of MLK and Mandela, it is essential that allies understand the movement and its operating principles.

The Black Lives Matter movement is the most recent phase of the 500-year global struggle for black freedom. It is not random. It is not disorganized.

The best way to change that old talk that black parents have with their children is to start a new talk between white and black parents. These conversations will make people uncomfortable, and they should. White parents should ask their black friends who are parents whether they have had “the talk” with their children. What did they say? What did their children say? How did it feel for them to have that conversation with their children? What’s it like not to be able to trust law enforcement in your own community?

We live in a culture that not only glorifies violence, but often celebrates its use against the “enemy" as the truest form of heroism and bravery. While I won’t get into the debate of whether violence is ever justified to preserve life (a much bigger conversation extending far beyond an 700-word post), I will say I’m deeply troubled by our assumption that violence is the only way to respond to a real or perceived threat.

For his final State of the Union address, President Obama delivered a characteristically eloquent and passionate speech. He issued a heartfelt call for unity and cooperation in a country whose political climate is just a few notches short of civil war. He asked us to consider how we might move forward as one nation, affirming our highest ideals rather than the hateful rhetoric of would-be despots.

Obama’s final State of the Union was in many ways a masterpiece of American political theater. He reminded us of the best of our tradition, calling us to live up to our history of welcoming the outsider and being a land of opportunity for all people. Despite the fact that this canonical history is to a great degree aspirational rather than actual, I was at many points uplifted to hear the president invite us to live into the more beautiful aspects of the American Dream.

In an abrupt change, the city of Chicago has made public video footage that documents the shooting death of Cedrick Chatman at the hands of Chicago police. The 17-year-old Chatman was shot and killed while running away from police. The officers claim he turned around and pointed a black object at them, an object which turned out to be a black iPhone box.

All of my favorite theologians are dying. David Bowie. Alan Rickman. A couple of years ago it was Pete Seeger. It is as if all my favorite theologians are moving on.

Please take me seriously as I say this. It has been a grief-striking week. Just like when Robin Williams passed, there is this void in my life, in my way of knowing God.

In marketing the film, Bay and the real-life men he portrays have stated that 13 Hours is not a political film. The goal, they say, is simply to show what happened, as it happened, and to recognize the courage and sacrifice of the people on the ground that day.

But it takes a more nuanced filmmaker than Bay (the creator of Bad Boys, Armageddon, and the Transformers films) to take an inherently political story like this one and truly make it free from bias. While 13 Hours doesn’t specifically call anyone out, or criticize (or endorse) the decisions of any particular leader or party, Bay and screenwriter Chuck Hogan mistake those qualities as the only ones required to make the film “non-political.”

Opponents of lessons on Islam often claim that Christianity takes a back seat in public schools’ religious instruction. That’s what an Augusta County, Va., mother argued recently when she opposed a teacher’s use of the Muslim statement of belief in a calligraphy exercise. She held a forum at a local church to protest how her religion wasn’t allowed in schools, but Islam was.

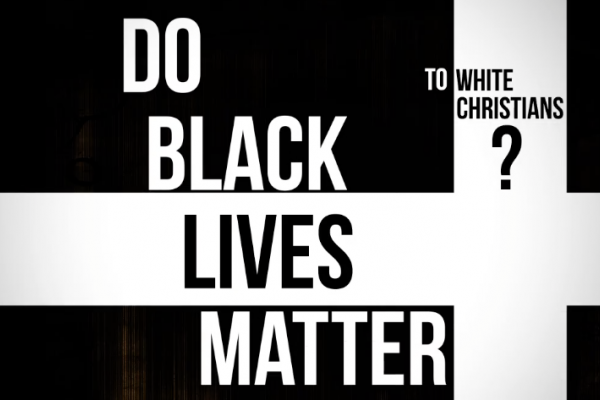

Most polls don’t matter much. But this one does. A recent Public Religion Research Institute survey has revealed a devastating truth: While about 80 percent of black Christians believe police-involved killings — like the ones that killed Tamir Rice, Laquan McDonald, and so many more — are part of a larger pattern of police treatment of African Americans, around 70 percent of white Christians believe the opposite … that they are simply isolated incidents.

Carson, a renowned neurosurgeon, has compared same-sex marriage to bestiality and pedophilia. He even suggested segregating bathrooms for the transgender population since it was unfair to make non-trans individuals uncomfortable. And this week, Carson referred to trans individuals as “abnormal” and said they should not be given “extra rights.” His comments on the LGBT community may seem outrageous to many — even to those in evangelical and mainline faith traditions who have left the “being gay is a choice” rhetoric in the past. Yet Carson, perhaps the most visibly religious presidential candidate, holds onto many of his anti-LGBT views.

If Carson’s faith affects his politics, it’s important to contextualize his conservative LGBT views with his church affiliation. Indeed, the Seventh-day Adventist Church espouses many similar views, which stem from a long, complicated history with the LGBT community.