Dec 17, 2015

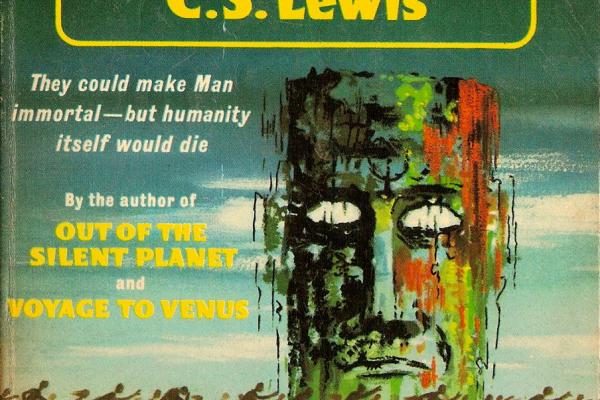

Lewis calls us to caution, to humility in the face of our quest for power. Just because we can does not mean we should. Even if you’re an optimistic transhumanist professor in England. That Hideous Strength is a devastating picture of that danger, more than fifty years ahead of its time.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login