“When they had all had enough to eat, he said to his disciples, ‘Gather the pieces that are left over. Let nothing be wasted.’”

John 6:12

When Raleigh Mennonite Church decided to fast from food waste for Lent, they didn’t know that 14 days in, the World Health Organization (WHO) would declare COVID-19 a pandemic. At a time when a core group of members planned on salvaging still-edible food from the dumpsters outside of grocery stores, hoards of Americans emptied the supermarket shelves of essentials like milk and bread and boxed wine.

For Jackie Parker and Craig Hargett — a married couple spearheading Raleigh Mennonite’s Lenten practice — fasting from food waste isn’t much of a sacrifice. Before they began dumpster diving six months ago, their grocery bill for their family of two adults and one child rang up to about $350 a month. But since they’ve been dumpster diving, they only spend $20 per month. So they decided to give up sugar, too.

After pausing dumpster diving for about a week in fear of all the unknowns that came with COVID-19, Parker and Hargett resumed their Lenten practice, along with many other members of their congregation. They decided that the zucchini in the dumpsters were no more likely than the zucchini on the shelves to harbor the virus (and it was easier to socially distance yourself in a dumpster than in a checkout line). While Parker and Hargett expected the dumpsters would provide less of a bounty as a result of widespread food hoarding, they still found the typical array of fresh produce (and scored two giant bottles of soap).

The pre-COVID-19 Lenten plan of fasting from food waste gave members a variety of ways to participate with varying levels of commitment. Some members’ jobs prevented them from joining in on the 10 p.m. dumpster dives, explained Rev. Melissa Florer-Bixler, the lead pastor of Raleigh Mennonite Church. Those who were able divvied up the dumpsters in town to collect from. Others pledged to eat all of the food in their pantries and fridges before purchasing any new perishables. And some committed to making work lunches at home rather than buying take-out food, which is often excessively packaged in plastic, paper, and foil.

“So much that we have been given as a gift just returns to a trash pile,” said Florer-Bixler.

To be precise, 40 percent of food in the U.S. goes uneaten.

“The problem is not that our world doesn’t produce enough food,” Florer-Bixler continued. “It is always about access. It is about waste. And about pollution. And about greed, both personal and corporate.”

At 22 percent of discarded municipal solid waste, food waste is the single biggest contributor to our landfills. And when food goes to the landfill to die, it does not simply return to the earth as nutritious soil. When uneaten food enters an environment like a landfill, suffocated by other trash and smell-suppressing clay, it is forced to deteriorate through an anaerobic process. Without the presence of oxygen, it releases methane gas as it slowly breaks down in this unnatural way, eventually contributing to 8 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Composting, on the other hand, mimics the aerobic decomposing process of nature outside of human meddling: a healthy combination of leaves, worms, microbes, and room to breathe.

Jackie Parker and Craig Hargett have five active composting piles. Even after they share their dumpster-diving spoils with other families, they often still have much left over. When their family first started dumpster diving, they were shocked by the amount of edible food they discovered. Parker asked a grocery store manager why her store didn’t consider donating to food pantries. The manager assured her that they were already donating as much as they could. Grocery stores and food pantries are restricted by sanitization and packaging standards that dumpster-diving Mennonites aren’t beholden to.

screen_shot_2020-04-02_at_9.42.35_pm.png

Lent in the time of the coronavirus has been defined less by fasting and restraint and more by hoarding and panic-shopping. When Americans purchase food, sanitizers, and medicine at two to three times the normal rate, this strains the resources for people who need them more: those living with disabilities, medical professionals, and people who rely on WIC and SNAP.

“The reality is that a lot of that food that was hoarded is now gonna get wasted,” Hargett said.

Of course, it’s hard to imagine Christians fully committing to sacrificial Lenten practices during a spring that has been characterized by so much taking-away in the name of social distancing. Many Catholic bishops across the U.S. have declared meat-eating permissible on Fridays “given the difficulties of obtaining some types of food and the many other sacrifices we are suddenly experiencing given the coronavirus,” as the Most Rev. James F. Checchio, the bishop of Metuchen in Piscataway, N.J., announced on Thursday.

This Lenten season, we’ve all been necessarily coerced into a nationwide fast from much of what we know and love: Students have given up in-person classes and graduation ceremonies. Young people have given up happy hours and pick-up basketball. Residents of assisted living facilities have given up visitors, and so on and on and on.

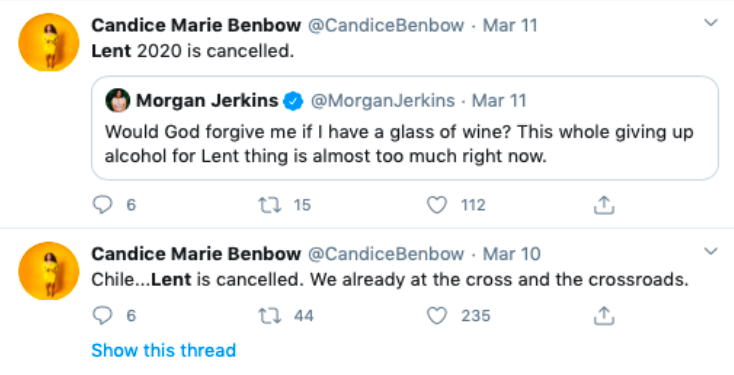

As the essayist and theologian Candice Marie Benbow put it, “Lent is cancelled. We already at the cross and the crossroads.”

Fasting has always been a complicated spiritual practice, though. At times it has devolved into a sort of New Years resolution, take two. More significantly, it has caused harm to those who have or have had an eating disorder. In 2017, when Lent fell in the same week as National Eating Disorder Awareness Week, Rev. Emmy Kegler put it this way:

"I don't want to preach a faith that can be so easily adapted to self-hatred and self-harm. I don't want to preach a Lent that can be easily turned into a guilt-ridden diet plan. I want a faith that doesn't care about chocolate. I want a faith that demands we fast from injustice, a faith that listens to the cry of the prophet: 'Is not this the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke?'"

In the midst of the virus and this weighty Lenten baggage, Raleigh Mennonite Church has found a compelling alternative.

The core group of RMC dumpster divers now goes on solo trips rather than group trips for the sake of social distancing. And by sharing the food they retrieve with other families in the church, the congregation is able to reduce the number of people who have to go to the grocery store. Parker explained that most often they leave the dumpster with a car full of items representing every food group. And they are continuing their typical sanitation practices of wearing gloves, washing produce in a solution of water and vinegar, and cooking anything that needs it.

Other members of RMC have felt an urge to grow more of their own food, reminiscent of the victory gardens movement that sprang up during World War I and II. During this food-insecure time, the government urged Americans to plant gardens wherever they could — roofs, church lawns, backyards, etc. At one point, these victory gardens accounted for nearly 40 percent of America’s food supply.

Crises, like Lent, can push us to reconsider our relationship to food and land.

Raleigh Mennonite Church members are not the only ones working to buff up their green thumbs. Now that every trip to the grocery store is fraught with potential exposure to COVID-19, many Americans are turning to growing some of their own fruits and vegetables. The New York Times reported a substantial uptick in seed-purchasing across the U.S. as people begin to question the reliability of our food supply chain in crisis times. The Victory Seed Company, for instance, is experiencing a current shipping backlog of 18 to 24 days.

Angel Cruz, another member of RMC, has incorporated seed-sharing into her Lenten practice. When she sent out a notice to her neighborhood that she would be putting seeds out on her front porch, about 20 people stopped by to collect some, occasionally offering other seeds in exchange.

It’s not all that surprising that this level of food intentionality is coming out of a Mennonite congregation. Historically, Mennonites have been defined by their resistance to violence, connection to the land, and proclivity for simple living. In 1976, the Mennonite Central Committee commissioned the now famous More-With-Less Cookbook. Authored by Doris Janzen Longacre, this cookbook encouraged Christians to share food resources and challenged “North Americans to consume less so others could eat enough."

I could hear echoes of this sentiment when Parker and Hargett explained to me their motivation for fasting from food waste: “With so many people who are food insecure it just seems criminal for this kind of food to be wasted,” Parker said.

Food justice advocates often see the dinner table as the place where so many justice lanes collide, including labor rights, economic injustice, food insecurity, climate justice, and more. Only about 75 people attend Raleigh Mennonite Church, but among them are dumpster divers, urban gardeners, farm gleaners, and those who work with Food-4-Thought, a volunteer group that rescues food from Trader Joe’s and distributes fresh fruit, vegetables, meat, and bread to about 90 households. The online flyer that announced RMC’s Lenten fast from food waste had a graphic of a sandwich and a quote from scripture:

“The field of the poor may yield much food but it is swept away through injustice” (Proverbs 13:23).

Raleigh Mennonite Church’s Lenten practice is just one part of what they are calling A Year at the Table. They have received a grant from the Calvin Institute to study their communion practices in relation to food systems and creation. Florer-Bixler sees communion as a Passover-like “celebration of liberation” and is pushing her congregation to see communion “as both a sacrament and a meal.”

On a typical communion Sunday, RMC uses donated day-old bread from a nearby bakery for communion. But now that the pews are empty and the doors to the bakery closed, they have again had to adjust their spiritual practices. On this past Sunday's Zoom call, Florer-Bixler asked her congregation to take communion with "a glass of something" and whatever bread was on hand, harkening back to lessons their congregation learned on a recent trip to El Salvador. There, they witnessed how communion can be synonymous with solidarity, survival, and celebration.

While megachurches in Louisiana, Ohio, and Florida have defied stay-at-home-orders by packing the pews, the doors to Raleigh Mennonite Church have been closed for weeks, and will remain closed on Easter Sunday. For the April 12 service, Florer-Bixler has asked everyone in her congregation to bake their communion bread using the same recipe. At least for a few of those families, that will likely contain yeast, salt, and a few cups of flour from the dumpster.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!