Workers

Through the years, we’ve written about the ways churches can help workers — and the way workers can help the church.

2. The Online Gig Economy’s ‘Race to the Bottom’

“ … while freelance websites may have raised wages and broadened the number of potential employers for some people, they’ve forced every new worker who signs up into entering a global marketplace with endless competition, low wages, and little stability.”

3. How Some Women of Color Were Left Out of the Minimum Wage Hike

“I see my job as the work of God, but God is angry because he sees that my job is making me sick needlessly and is mistreating me. We have been treated like slaves.”

The first element that gets blown up by the parable is the motive of the landowner. Sometimes preachers, trying to fill in the gaps in the story, will surmise something like, “So the landowner, needing more laborers to work the vineyard, went back to the marketplace,” but this distorts the parable.

For much of its long history in the U.S., the Catholic Church was known as the champion of the working class, a community of immigrants whose leaders were steadfast in support of organized labor and economic justice – a faith-based agenda that helped provide a path to success for its largely working-class flock.

In recent decades, as those ethnic European Catholics assimilated and grew wealthier, and as the concerns of the American hierarchy shifted to battles over moral issues, such as abortion and gay marriage, traditional pocketbook issues took a back seat.

Recently, I marched with McDonald’s workers from three dozen cities to the company’s corporate headquarters outside of Chicago. After they refused to leave the corporate campus of the fast-food giant with its $5.6 billion in profits last year, 101 workers were arrested.

I knew I had to come when the workers invited me to share some of the lessons we have been learning in North Carolina about civil disobedience — and moral support.

I watched my new friends sit down. I watched the police gather. I prayed with the McDonald’s workers as the police looked on and then slapped plastic handcuffs on more than 100 of the workers and arrested them.

I could not help but think of the historic arc of the civil rights movement. For all the gains we have been making, the treatment of low-paid workers by some of the most profitable corporations in the world ranks high in the more significant causes of the growing inequalities in the U.S.

The American workplace, like the rest of U.S. society, is becoming more religiously diverse and that is raising concerns about employer accommodations for believers — and increasing the odds for uncomfortable moments around the water cooler.

Yet one potential flashpoint among workers does not involve new immigrant faiths but rather two indigenous communities: white evangelicals and unaffiliated Americans who constitute one of the fastest-growing segments of the population.

A major factor contributing to workplace conflict, according to a survey released on Friday, is that evangelicals — whose religious identity is tied to sharing their beliefs — are much more likely to talk about their faith at work than other religious and nonreligious groups.

Environmental activist Bill McKibben took part in the July 5-6 Healing Walk, a spiritual gathering in northern Alberta, Canada, focused on the destruction—to the immediate environment and to the climate itself— caused by tar sands oil extraction and the Keystone XL pipeline across the U.S.

TO WALK, SLOWLY, across the tar sands complex of Alberta is to see our real-life equivalent of The Lord of the Rings’ Mordor. It really is as bad as everyone says. On this one eight-mile loop, we saw vast stretches of muskeg turned into dry, sandy desert; we saw dry-sandy desert that had been further converted into inky tailings lakes; and we were never out of earshot of the cannon that fire all day and all night to keep ducks from landing in the toxic waters. This goes on forever. The most comprehensive way to see it is from the air, I guess, but the best way to feel it is on foot.

Especially if you’re walking with the people who know this land best—have known it for thousands of years. Each year since 2010, local First Nations groups have organized a Healing Walk through the tar sands, and this year’s fourth iteration was by far the largest. Hundreds of people from around the continent camped for several days in a stretch of nearby boreal forest, held workshops and ceremonies, and then emerged for the hike through the industrial barrens.

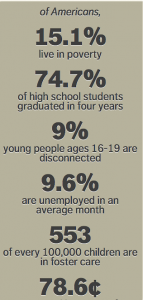

In their annual Labor Day statement, the U.S. Catholic bishops call for “national economic renewal that places working people and their families at the center of economic life.” Issued by Bishop Stephen Blaire of Stockton, Cal., chair of the Committee on Domestic Justice and Human Development, the statement emphasizes the reality that “Millions of Americans suffer from unemployment, underemployment or are living in poverty as their basic needs too often go unmet. This represents a serious economic and moral failure for our nation.”

The bishops then cite related issues in the news.

On the deficit:

“Public officials rightfully debate the need to reduce unsustainable federal deficits and debt. In the current political campaigns, we hear much about the economy, but almost nothing about the moral imperative to overcome pervasive poverty in a nation still blessed with substantial economic resources and power.”

A playlist for the working class: Ten songs in honor of May Day and workers everywhere.

John Lennon, "Working Class Hero"

This song from John Lennon's first post-Beatles solo album, 1970's John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, is about working class folks being "processed" into the middle class or the "machine," according to what Lennon told Rolling Stone magazine in an interview the same year the album released. "A working class hero is something to be," is the song's mantra and refrain.

Today is May Day – an historic day of protest and action for the working class. This year, in light of the Occupy movement, many are hopeful of the resurgence this day can bring in the fight for national against economic injustice.

About every five years the Farm Bill addresses a broad set of food and agricultural policy issues. Commodity price supports, farm credit, trade, agricultural conservation, research, rural development, energy, and foreign and domestic food programs were just some of the issues included in the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008, as the last Farm Bill legislation was officially titled.

The Farm Bill is also known for the broad range of policy stakeholders who work on it, including state organizations, national farm groups, commodity associations, conservation advocates, rural development organizations, and faith-based groups.

But even with its inclusive set of policy issues and actors, the Farm Bill is notable for one issue policymakers and advocates doesn’t touch: People who work on farms.

During interviews with more than a dozen Afghan women leaders, researchers, international aid workers and former Afghan government officials, we learned of persistent dangers and threats to the country's future.

Afghan women face continuing repression. They are witnessing the erosion of previous gains as Taliban control spreads in the countryside and reactionary warlord influence increases within the Kabul regime. The government's own security forces are often responsible for violations of women's rights. Check back in a few days for a more detailed account of what we learned.

The withdrawal of foreign forces will produce an economic crisis for the government of Afghanistan, which remains almost completely dependent financially on the U.S. and other foreign governments, especially to pay for its huge 300,000-person security forces. I wrote about this funding failure in an earlier post.

A new security agreement between Kabul and Washington is likely to call for the continued presence of U.S. military forces in the country beyond the 2014 transition deadline. This is seen as necessary to provide security for Kabul, but it could also have the effect of prolonging the insurgency and impeding prospects for reconciliation.

It was clear from what we heard that maintaining security requires more than deploying a large number of troops.

Nearly 50 million Americans are currently living below the poverty line (that is $22,000 for a household of four) and half of them are working full time jobs.

In our current economic system, the "happiness" of the super-elite is secured while the lives, liberty, and access to basic needs of the rest suffer. This isn't the American Dream and it isn't God's dream either.

Perhaps the most important finding from the report is that we have both the experience and the policy tools necessary to cut poverty in half.

Between 1964 and 1973, under both Democratic and Republican administrations, the U.S. poverty rate fell by nearly half (43 percent) as a strong economy and effective public policy initiatives expanded the middle class.

Similarly, between 1993 and 2000, shared economic growth combined with policy interventions such as an enhanced earned income tax credit and minimum wage increase worked together to cut child poverty from 23 percent to 16 percent.

We can't do this alone.

In our own time the "jobs" rhetoric from both the right and the left ignores the power grabs and power differentials that led to the hemorrhaging of American jobs in the first place. The simple truth is that multinational corporations could make more money for their shareholders by outsourcing jobs to third-world countries so that is what they did.

This was not a moral dilemma for CEOs; it was a "sound business decision." And the gospel according to free-market capitalism (the USA's true religion) preaches that what is good for American business is good for America.

| The Daily Show With Jon Stewart | Mon - Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| Mexed Out | ||||

| ||||

How ironic that for all the protests going on about unemployment these days that a parallel debate is occurring in our agricultural sector: What to do about a shortage of workers to pick crops or care for livestock on U.S. farms.

In his column last week, Sojourners chief Jim Wallis talked about his frustration with the perennial misuse of the word "evangelical" by various media to describe folks and ideas that, in his view, and that of many of us who self-describe as evangelicals, don't bear any resemblance to what we understand that term to actually mean.

Below is a compilation of recent media reports where the word "evangelical" is invoked. When you read these, evangelical brothers and sisters, do you recognize yourself in how the word is used and defined? Or does it ring false to you and your understanding of what "evangelical" really and truly means?

Wall Street has been devastating Main Street for some time. And when the politicians -- most of them bought by Wall Street -- say nothing, it's called "responsible economics." But when somebody, anybody, complains about people suffering and that the political deck in official Washington has been stacked in favor of Wall Street, the accusation of class warfare quickly emerges. "Just who do these people think they are," they ask. The truth is that the people screaming about class warfare this week aren't really concerned about the warfare. They're just concerned that their class -- or the class that has bought and paid for their political careers -- continues to win the war.

So where is God in all of this? Is God into class warfare? No, of course not. God really does love us all, sinners and saints alike, rich and poor, mansion dwellers and ghetto dwellers. But the God of the Bible has a special concern for the poor and is openly suspicious of the rich. And if that is not clear in the Bible nothing is.