Reading

Novelist Edwidge Danticat expressed a similar sentiment in Create Dangerously, her 2010 memoir about making art in exile. Reflecting on the aftermath of the earthquake that had struck her home country of Haiti that year, she wrote, “I did what I always do when my own words fail me. I read.” We share this human practice of story sharing and story seeking. Danticat writes of her “desire to tell some of [her] stories in a collaged manner, to merge [her] own narratives with the oral and written narratives of others.” Through the transformative power of creating and remembering, we connect to the threads of humanity, discovering the woven patterns that are formed through our stories.

If the empathy debate teaches us anything, it’s that for all its power, empathy on its own will not solve our problems.

The book of Job is remarkably relevant in this moment and speaks to our present condition.

LATELY I'VE BEEN reading nonfiction books, finding their less-debatable truths a comforting contrast to the fearsome unpredictability of today’s world. Previously, I had blocked out that world by reading fiction from the horror genre, but stories about people facing unspeakable terrors just seem too cheery these days.

So I’ve settled on works that detail the hard facts of science, lately the origins of humankind. Did you know that we modern human beings are only one of several species of humans throughout evolutionary history? (Evolution being what Charles Darwin dreamed up to cover his childhood disappointment that unicorns weren’t allowed on Noah’s ark. So sad.)

I didn’t realize that we current humans—called homo sapiens, which is Latin for “smarter than those Neanderthal doofuses” (doofi? )—didn’t evolve as one species, seamlessly blending into each next version, like that drawing of hunched figures emerging from the sea to eventually straighten to full height and check email. No, each human species came into existence in a distinct arc of development.

Neanderthals, which preceded us, were actually stronger and had larger brains than the later homo sapiens, but lived virtually unchanged for millennia, their tools never improving, their nomadic lifestyle never maturing into more organized communities. They stubbornly stuck to their ways, and might even have said, “Hey, why reinvent the wheel?” had they invented the wheel in the first place. Which they didn’t.

Fire they mastered quickly, of course, using it for cooking and warmth, but the programmable thermostat never occurred to them.

FEWER AMERICANS ARE reading for pleasure. According to the latest American Time Use Survey, the portion of Americans who read just for the joy of it on a given day has fallen by more than 30 percent since 2004.

I’m choosing to resist the tyranny of trends—by reading more. Lately that’s meant sinking into a sprawling novel about trees, who, it turns out, are an active force, not just part of the scenery. The Overstory, by Richard Powers, is also about community, family, conscience, love, and fighting the powers.

My editorial colleagues are also making time to read. Their stacks include sci-fi (Blackfish City, by Sam J. Miller); historical fiction ( Homegoing, by Yaa Gyasi and Pachinko by Min Jin Lee); a novel spanning Roman-occupied Jerusalem to the 21st century (Eternal Life, Dara Horn); short stories (The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, by Denis Johnson); poetry ( Don’t Call Us Dead, by Danez Smith); essays (Feel Free, by Zadie Smith); biography ( Galileo’s Daughter: A Historical Memoir of Science, Faith, and Love , by Dava Sobel); and many more.

Below are some nonfiction books that might fit in your leisure reading mix.

Billion Photos / Shutterstock

NOT LONG AFTER graduating college, I read everything I could find about various expressions of Christian community. Somewhere along the way, I stumbled upon the stories of Dorothy Day, Peter Maurin, and the other Catholic Workers who would follow in their footsteps. I remember being immediately captivated by the Catholic Worker vision for hospitality houses that were community hubs for both action—growing food, feeding the hungry, protesting American militarism—and learning—cultivating conversation and reflection on radical Christian faithfulness and the socioeconomic vision that defined the movement.

Although perhaps more widely admired for their activism and works of mercy, the Catholic Workers have long published a newspaper that is a catalyst for their social vision—fusing the stories of scripture, saints, and literature with the ubiquitous challenge to live faithfully in an age marked by greed and violence. In the words of Maurin, an essential part of their mission is to make “workers out of scholars and scholars out of workers.”

Image via Saida Shigapova / Shutterstock.com

In 2005, Amina Wadud stepped in front of a crowd of one hundred Muslims, women and men, to offer a sermon and lead them in prayer — something previously unheard of for a woman to do. Wadud has been vocal about gender equality in Islam for decades. She is a prominent speaker, writer, and scholar of Islamic studies. But I didn’t know of her until my senior year of college. In my last class as an undergraduate student, I decided to take a class on Islam. I was intrigued by our reading list at the beginning of the semester, but Amina Wadud and her book, Inside the Gender Jihad: Women’s Reform in Islam, were just words on my syllabus.

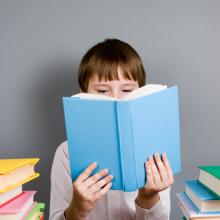

Many boys at my school struggle with reading. Most are more interested in video games and outdoor activities than books. Our school is not an anomaly.

Across the country adults have grappled with the lag in boys’ reading interest and skills. According to the 2010 Kids & Family Reading Report sponsored by Scholastic, fewer than 40 percent of boys said that reading outside the classroom is important.

So when my school’s coordinator asked me to start a lunchtime reading group to get boys interested in reading, I was excited. The first fourth-grade literary lunch would be called BEREAders (Berea Readers).

I am excited about reading.

During my first year as a second-grade teacher, I struggled with classroom management. I am a soft-spoken person by nature and habit. I didn't have the experience to help me set up great rules and procedures for my students. My classroom was noisy and chaotic. I think you could hear us all around the school.

A well-meaning colleague stopped me one day after school and offered, "Trevor, you need to find your teacher voice. Most of the children at our school won't listen to you unless you yell at them. You need to show them who's boss."

After five years of teaching, I agree that it is important to find your teacher voice. I disagree, however, that your teacher voice needs to be mean and bossy. I found my voice. It’s nurturing and supportive and one that students can internalize for positive growth and change.

I thought about this teacher voice when I met 7-year-old Maria. On her first day in reading intervention classroom, she made a mistake on a skill sheet. She asked for an eraser but I said, "Don't worry if you make a mistake. You don't have to erase it. Just cross it out and fix it. I'll never be angry with you if you make a mistake. I just want you to try to fix it."

In Roald Dahl's classic children's book James and the Giant Peach, 7-year-old orphan James Henry Trotter escapes his two rotten, abusive aunts by crawling into a giant peach. The peach rolls, floats, and flies him to a new life of wonder and love.

I'm reading this book aloud for the first time, and my listeners are spellbound by the story, especially the part where the very small old man opens the bag filled with magical crocodile tongues that will help a barren, broken peach tree grow fruit as big as a house.

"There's more power and magic in those things in there than in all the rest of the world put together," says the man.

There is.

Editor's Note: Over the next two weeks, Sojourners is celebrating our teachers, parents, and mentors as children across the country head back to school. We'll offer a series of reflections on different aspects of education in our country.

My elementary school is a Title I school. About 97 percent of our students qualify for free and reduced lunch and Medicaid. Research shows us that many children raised in poverty struggle to learn to read.

Common sense tells us that children who don't learn to read can't read to learn. They often reach a frustration level with school by the time they're in the third grade. According to the U.S. Department of Education, 70 percent of low-income fourth-grade students can't read at a basic level. I often wonder, "What can I do in my day-to-day work as a teacher to help?"

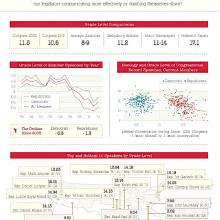

According to the Sunlight Foundation:

Congress now speaks at almost a full grade level lower than it did just seven years ago, with the most conservative members of Congress speaking on average at the lowest grade level, according to a new Sunlight Foundation analysis of the Congressional Record using Capitol Words.

Of course, what some might interpret as a dumbing down of Congress, others will see as more effective communications. And lawmakers of both parties still speak over the heads of the average American, who reads at between at 8th and 9th grade level.

The summer that I was 17 years old, I, who was born of missionary parents in China, was rooming with a friend whose parents were missionaries in Africa. Although our mothers had been friends long before we were born, Mary and I first met as summer employees at our denomination’s conference center when she came back to the States to go to college. World War II had driven my parents out of China, so I had lived, since the age of 8, in various places in the southern United States.

One night after the day of waitressing was over, Mary began to read aloud to me Alan Paton’s novel Cry, the Beloved Country. At first it was just the sound of Mary’s Africa-haunted voice caressing the beauty of Paton’s language that kept me wide awake and enthralled. But gradually, chapter by chapter, that beauty told me of the unspeakable oppression and tragedy that was South Africa’s story for too many years. I’m not sure exactly when it happened, but suddenly one night the book came alive for me in a new way. I saw for the first time that the tragedy of South Africa was the tragedy of the American South, where I had been blind to the oppression from which I as a white person had been exempt. I began to cry, sob rather, for my own thoughtless sins and the sins of my people.

I look back on those tears as a turning point in my young life. I did not leave all my sins and fears on that wet pillow—I’m still not free from them—but I know my life began to change that night because of a book.

Caroline Gordon, in her book How to Read a Novel, speaks of the reading of a great book as a “conversion experience.” You are not the same person when you finish the last page, she says, that you were when you first sat down to read. I believe, from my own experience, that Gordon is right, and that is why I think reading is so important to our growth as wise and compassionate human beings.

David Denny teaches English at De Anza College in Cupertino, California.